1. Baseball

It’s often called “America’s pastime,” but baseball didn’t exactly sprout from U.S. soil. Versions of the game were played in England as early as the 18th century, known as “rounders.” Immigrants brought those bat-and-ball traditions across the Atlantic, where they evolved into the game Americans now claim as their own. Abner Doubleday might get the mythic credit, but the real roots are unmistakably British.

What makes this worth noting is how baseball became so central to American identity despite its international origin. The game was polished and popularized in the U.S., sure, but its DNA traces back to English schoolyards. It’s a great example of how cultural imports can become national symbols over time. Basically, America took something old and made it feel brand new.

2. Hot Dogs

Hot dogs feel like the ultimate American cookout food, yet their story starts in Germany. The humble sausage—specifically the frankfurter and the wiener—came from Frankfurt and Vienna long before they hit U.S. ballparks. German immigrants brought their recipes to the States in the 1800s, selling sausages from carts in New York and Chicago. Eventually, the bun was added for convenience, and the “hot dog” was born.

It’s worth including because it shows how immigrant influence helped shape American street food. The idea wasn’t to copy—it was to adapt, turning a European snack into a cultural staple. Even the term “hot dog” came about later, as vendors leaned into playful marketing. So next time someone calls it an all-American food, remember it started across the ocean.

3. The Internet

The United States gets a lot of credit for inventing the internet, but it’s more accurate to say America built on a global effort. ARPANET was definitely a U.S. defense project, but many of the foundational technologies came from elsewhere. British computer scientist Donald Davies coined the term “packet switching,” which became crucial for online communication. And the World Wide Web itself was created by Tim Berners-Lee in Switzerland.

This entry matters because it reminds us how collaboration drives innovation. While America provided the infrastructure, other nations contributed equally vital pieces. The web we use today wouldn’t exist without that international teamwork. It’s a digital patchwork quilt with many hands behind the stitches.

4. The Telephone

Alexander Graham Bell patented the telephone in the U.S., but the race to invent it was truly international. Italian inventor Antonio Meucci had created a voice communication device years earlier, though he lacked the money to patent it properly. Many historians argue Bell’s version built directly on Meucci’s earlier work. In fact, the U.S. Congress formally recognized Meucci’s contributions in 2002.

Including this one is about setting the record straight. The story of the telephone shows how innovation isn’t always about who gets the patent—it’s about who gets remembered. Bell’s success came from timing, resources, and marketing, not total originality. Meucci’s forgotten legacy makes this a fascinating footnote in American invention lore.

5. Democracy

It’s tempting to think of democracy as an American export, but the idea long predates the Declaration of Independence. The ancient Greeks were holding democratic assemblies in Athens more than 2,000 years before 1776. Even the Iroquois Confederacy, right here in North America, had its own sophisticated democratic system before European settlers arrived. The U.S. model drew heavily from both examples.

This inclusion highlights how America didn’t invent democracy—it refined it. The Founding Fathers studied classical systems and indigenous practices when designing their own. They weren’t creating something brand new, but rather remixing history’s best ideas. It’s a powerful example of learning from the past to shape the future.

6. The Automobile

Henry Ford made cars accessible, but he didn’t invent them. The first true automobile came from German engineer Karl Benz in the 1880s. Benz’s Patent-Motorwagen was the foundation for everything that followed, though Ford revolutionized the manufacturing side with his assembly line. America perfected car production, not car creation.

This is a great case of innovation through optimization. Ford’s genius was in making cars affordable for everyday people, turning a luxury item into a necessity. That’s why we remember him, but Benz deserves the origin credit. It’s a reminder that invention and innovation aren’t the same thing.

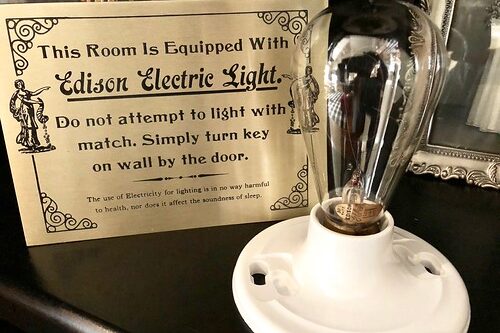

7. The Light Bulb

Thomas Edison is the household name, but he wasn’t the first to make a light bulb. British inventors like Humphry Davy and Joseph Swan had already been experimenting with electric light decades earlier. Edison’s breakthrough was refining the filament and creating a system for mass production. He made it practical, not original.

The light bulb belongs here because it captures how America often wins the “implementation” game. Edison took a good idea and made it work commercially, which is a skill in itself. But the light bulb’s roots stretch across the Atlantic. Innovation, it turns out, is often a global relay race.

8. Jeans

Nothing says “American fashion” like a pair of blue jeans—but their creator wasn’t born in the U.S. Levi Strauss was a German immigrant who partnered with tailor Jacob Davis, a fellow European. Together, they patented riveted work pants during the California Gold Rush. The fabric itself, denim, was inspired by a French material called “serge de Nîmes.”

This story is pure Americana built on international threads—literally. It shows how immigration and global trade shaped American industry. Jeans might have become a U.S. icon, but they owe their durability and design to ideas imported from abroad. The irony only makes them more fascinating.

9. The Credit Card

Swiping plastic feels like a quintessentially modern American habit, but the concept came from British innovators. In the early 1940s, a London company called “Charge-It” tested early versions of store cards. The idea took off in the U.S. a decade later with Diners Club, which turned it into a lifestyle. America didn’t invent credit—it scaled it.

It’s an important inclusion because it shows how America excels at amplification. The U.S. transformed a local convenience into a massive financial industry. The culture of “buy now, pay later” became deeply American, even if its origin wasn’t. It’s a case study in turning a clever idea into an empire.

10. The Microwave Oven

Most people associate the microwave with American postwar convenience, but its roots lie in radar research. British scientists during World War II discovered that radar waves could heat food accidentally. American engineer Percy Spencer took that concept and developed the first commercial microwave oven in 1945. So while the product became American, the science behind it was shared.

This one matters because it illustrates how war-driven technology often crosses borders. Without British experimentation, Spencer might never have stumbled on his famous melted chocolate bar. It’s a perfect example of international serendipity. The invention’s origin is more team effort than solo act.

11. The Airplane

The Wright brothers made history in 1903, but they weren’t working in isolation. European inventors like Sir George Cayley and Otto Lilienthal had already developed gliders and aerodynamic theories that made flight possible. The Wrights built on that foundation, adding powered control and steering. Their contribution was vital—but not from scratch.

It’s here because the myth of total American invention overlooks decades of groundwork. The Wright brothers succeeded because they paid attention to global experimentation. Their breakthrough came from combining European science with American ingenuity. Flight, like so many things, was born of cooperation.

12. The Sandwich

Few foods feel as “American lunch” as the sandwich, but the name itself tells the story. It’s named after John Montagu, the 4th Earl of Sandwich, who popularized the idea of putting meat between bread in 18th-century England. Immigrants brought the concept across the Atlantic, where Americans super-sized it and gave it personality. The result? BLTs, subs, and PB&Js galore.

It’s worth including because it shows how food travels and transforms. America made the sandwich its own with creativity and variety, but the basic idea wasn’t born here. The U.S. turned a British convenience into a cultural staple. That blend of practicality and flair is what makes it so American—ironically.

13. The Computer

America gets plenty of credit for Silicon Valley and personal computers, but the earliest machines came from Europe. British mathematician Charles Babbage designed the first mechanical computer in the 1800s, and Alan Turing laid the groundwork for modern computing. The first electronic digital computer, Colossus, was built in England during World War II. U.S. contributions like ENIAC came shortly after, expanding the field.

This entry underscores how global cooperation shaped the digital age. The U.S. dominated commercialization and innovation, but the foundational thinking came from elsewhere. Computers became a global invention refined in American hands. It’s a perfect note to end on—proof that “borrowing” often leads to brilliance.

This post 13 Supposed “Inventions” America Actually Borrowed From Somewhere Else was first published on American Charm.