1. Economic Boom vs Uneven Prosperity

The remembered America often begins with the postwar economic boom, when growth was strong and wages rose for many workers. This period is frequently recalled as a time when hard work reliably led to a better life. In lived America, that prosperity was real but highly uneven. Gains were concentrated among white men in manufacturing, construction, and other unionized industries.

This difference matters because nostalgia turns a partial experience into a national one. Black Americans, women, and many immigrants were systematically excluded from the best jobs and benefits. Policies and social norms narrowed who could participate in that boom. Remembering the boom without its limits distorts how economic inequality developed.

2. Suburban Dream vs Structured Segregation

The remembered America often features expanding suburbs filled with affordable homes and young families. These neighborhoods are recalled as symbols of optimism and upward mobility. In lived America, access to those suburbs was tightly controlled by race and policy. Redlining, restrictive covenants, and lending discrimination shaped who could buy and who could not.

This distinction is crucial because homeownership drove wealth accumulation. Families excluded from suburbs missed decades of rising property values. The memory celebrates the comfort of suburban life without acknowledging the barriers to entry. That omission helps explain modern racial wealth gaps.

3. Strong Middle Class vs Narrow Eligibility

The remembered America is often described as a golden age of the middle class. Popular memory suggests most families enjoyed financial security and modest comfort. In lived America, the middle class existed but was narrower than remembered. Many households hovered just above poverty and remained economically fragile.

This matters because the size of the middle class is often exaggerated in hindsight. A single medical bill or job loss could still be devastating. Government programs reduced hardship but did not eliminate it. Remembering a universal middle class masks how conditional that security really was.

4. Stable Jobs vs Precarious Labor

The remembered America includes long-term jobs with pensions and predictable hours. These roles are often imagined as the norm rather than the exception. In lived America, job stability depended heavily on industry, race, and geography. Agricultural, domestic, and service workers rarely had such protections.

This gap matters because labor law excluded entire categories of workers. Those exclusions were not accidental and shaped economic outcomes for decades. The memory of stability overlooks how many people lived with constant insecurity. It also complicates claims that modern precarity is entirely new.

5. Simple Family Life vs Constrained Choices

The remembered America often highlights clear family roles and social stability. One parent worked, the other stayed home, and families appeared cohesive. In lived America, those arrangements were often driven by limited options rather than preference. Women faced legal and cultural barriers to employment, credit, and education.

This difference matters because simplicity is mistaken for satisfaction. Many women were economically dependent even when unhappy or unsafe. Divorce, contraception, and workplace access were restricted. Remembering only harmony ignores the cost of enforced conformity.

6. Law and Order vs Unequal Enforcement

The remembered America is often portrayed as safer and more orderly. Crime is recalled as lower and communities as more trusting. In lived America, law enforcement was not experienced equally. Policing and sentencing disproportionately targeted Black and marginalized communities.

This matters because perceptions of safety depend on who was being protected. Some neighborhoods experienced aggressive surveillance rather than security. Crime data varied widely by location and era. Nostalgia often confuses selective safety with universal order.

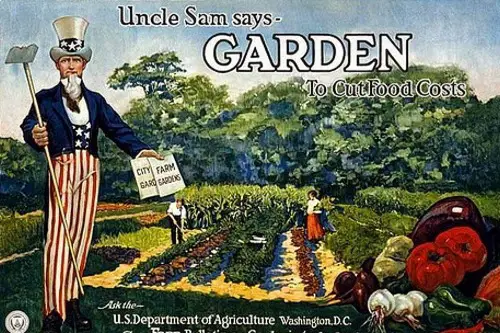

7. Civic Unity vs Social Exclusion

The remembered America emphasizes shared values and national cohesion. Events like wartime mobilization are cited as evidence of unity. In lived America, that unity frequently excluded dissenters and minorities. Political repression, loyalty tests, and discrimination were common.

This distinction is important because unity often came at the cost of silence. Labor activists, civil rights organizers, and antiwar voices faced surveillance and punishment. Consensus was sometimes enforced rather than organic. Remembering harmony without coercion oversimplifies the past.

8. Affordable Education vs Limited Access

The remembered America highlights cheap college tuition and expanding universities. Education is recalled as an open ladder to success. In lived America, access depended on race, gender, and location. Many institutions were segregated or informally exclusionary.

This matters because education shaped lifetime earnings. While tuition was lower, attendance was far from universal. Black students and women were often steered away from certain fields or schools. The memory of affordability ignores who was allowed to enroll.

9. Strong Communities vs Silenced Conflict

The remembered America often features close-knit communities where neighbors knew each other. These places are remembered as supportive and stable. In lived America, community cohesion often relied on conformity. Those who differed faced pressure, ostracism, or worse.

This difference matters because belonging was conditional. LGBTQ people, religious minorities, and political outsiders often lived double lives. Conflict existed but was pushed underground. Remembering warmth without tension creates an incomplete picture.

10. Opportunity for All vs Conditional Mobility

The remembered America is framed as a land of open opportunity. Upward mobility is treated as widely attainable. In lived America, mobility existed but was constrained by race, class, and geography. Structural barriers limited who could move up.

This matters because mobility statistics varied sharply across groups. Many people remained in the same economic position as their parents. Opportunity was real but unevenly distributed. The memory turns possibility into probability.

11. A Better Past vs A Selective Memory

The remembered America often feels better simply because it is remembered. Time smooths hardship and sharpens highlights. In lived America, daily life included stress, exclusion, and uncertainty alongside progress. Memory edits out what no longer fits the story.

This distinction matters because nostalgia shapes modern politics and culture. Policies are often justified by an imagined return rather than historical reality. Remembering selectively can block honest solutions. Understanding lived experience helps separate myth from history.

This post The Difference Between Remembered America and Lived America was first published on American Charm.