1. Deindustrialization: factories that used to hum went quiet

Between the late 1990s and the 2010s, manufacturing employment in the Midwest fell and shifted in ways that hollowed out whole communities. Plant closings and the relocation of production abroad or to automated lines removed reliable middle-class jobs overnight. For people who grew up expecting steady factory work, the change felt less like an economic shift and more like a betrayal. The pain showed up in empty storefronts, rusting plants, and a deepening sense that stability had been taken for granted.

Those job losses rippled outward: local tax bases shrank, small businesses lost customers, and municipal services began to fray. Generations who relied on defined-benefit pensions watched lifetime security get thinner. What followed wasn’t just unemployment — it was a cultural unpicking of whole towns that had been organized around steady industrial work. The result was communities that were poorer, older, and less resilient to the next shock.

2. Population loss: people voted with their suitcases

Many Midwestern cities and rural counties saw steady declines in population over two and three decades, especially places tied to declining industries. Young people left for education and jobs elsewhere, and birth rates fell in many of the hardest-hit counties. The visible effect was fewer kids at schools, shuttered hospitals, and neighborhoods that never came back after waves of out-migration. For anyone who stayed, daily life became a negotiation with fewer services and fewer neighbors to lean on.

Population loss also changed political and economic math: labor pools thinned, property values stalled, and investment dried up. That made it harder to attract the very industries or amenities that could have reversed the decline. It’s not just numbers on a chart — it’s the loss of barbershops, team sports, PTA volunteers, and other small pieces that make a place feel alive. Those absences add up quickly and become self-reinforcing.

3. The 2008 crash and foreclosure wave: the home you knew disappeared

When the housing bubble popped, many Midwestern homeowners — particularly in Great Lakes states — faced waves of foreclosures that wiped out household wealth. While the national conversation often focused on Florida or Nevada, several Midwestern metros and suburbs experienced concentrated distress that scarred neighborhoods. Foreclosures didn’t just remove people from houses; they hollowed out consumer demand and left tax rolls lighter. Neighborhoods that had been stable for decades suddenly carried boarded windows and a sense of abandonment.

The local consequences were practical and brutal: schools lost funding, municipal budgets tightened, and rehabilitation efforts struggled to keep up with vacancy. For families that stayed, access to credit and opportunity narrowed, making recovery feel like an uphill climb. Public policy helped in places, but rebuilding trust and investment took years — if it happened at all. The foreclosure crisis rewrote expectations about home as a secure store of value for a generation.

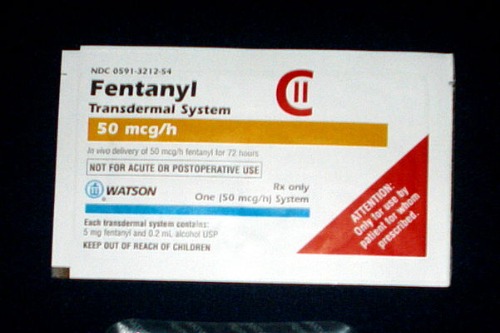

4. The opioid epidemic and fentanyl’s arrival: health emergencies became economic ones

Starting in the mid-2000s and accelerating into the 2010s and 2020s, opioid overdoses surged across the Midwest, with synthetic fentanyl later turning single overdoses into community-wide tragedies. The epidemic cut across towns of every size, taking workers in their prime and adding new pressure to families and local health systems. Loss of life translated immediately into lost incomes, fractured households, and increased demand for social and medical services that many rural hospitals were ill-equipped to provide. The human toll became a chronic economic drag, not just a public-health headline.

Community responses varied, from harm-reduction programs to law enforcement crackdowns, but the pace of deaths often outstripped local capacity to respond. Families carried the invisible costs — children in foster care, exhausted caregivers, and employers grappling with unpredictable absences. The epidemic also shifted public budgets toward emergency responses and away from long-term investment. In short, it turned private tragedies into public liabilities that many hard-hit places still haven’t shaken off.

5. Farm consolidation and the erosion of family agriculture

Over the past few decades, Midwestern agriculture concentrated into larger operations while small and mid-sized family farms dwindled. Advances in technology, economies of scale, and market forces pushed production onto bigger plots and into fewer hands, changing the social fabric of rural towns. When small farms disappear, so do the local businesses and services that supported them, from feed stores to school enrollments. That structural shift increased productivity but also hollowed out rural economies and made recovery from shocks harder.

The consolidation trend also shifted political power and community identity — big agribusinesses behave differently than multi-generation family operations, and those differences matter at kitchen-table and county-seat levels. Fewer farm owners mean fewer voters with strong ties to local schools and civic life, and that civic thinning makes community organizing and local development harder. Younger people with farming backgrounds are less likely to inherit a full-scale operation, so the pathway to staying in place narrows. All of this feeds into a cycle where economies get less diverse and more fragile.

6. Retail collapse and downtown decay: the mall that closed was a canary

As national retailers shrank and e-commerce rose, downtowns and local shopping strips lost steady foot traffic that once supported dozens of small firms. Big-box and mall closures were more than retail stories; they were community rituals that signaled the loss of gathering places and part-time jobs for teens and seniors. Vacant storefronts made neighborhoods feel unsafe and uninviting, which discouraged the small reinvestments that create momentum. The result was an accelerating visual and economic decline where once-busy streets became places people avoided after dark.

Some towns tried to convert empty malls into mixed-use centers or public space, with mixed success and heavy upfront costs. Where reinvention worked, it usually required aligned leadership, funding, and luck — all in short supply in places already dealing with job and population losses. When it didn’t, blight became permanent and property tax bases shrank further. Retail collapse therefore functioned as both symptom and accelerant of wider decline.

7. Automation and the shrinking quality of work

Even where jobs remained, automation changed what “work” meant: fewer full-time roles, fewer benefits, and more contingent or part-time employment. Factories that once employed hundreds now run with a skeleton crew overseeing robots, and logistics hubs automate tasks once done by humans. That shift tightened household budgets and made it harder for workers to get stable careers without retraining or relocation. Wages stagnated in many sectors, so headline economic statistics looked healthier than real life in dozens of counties.

For towns built around a handful of employers, the quality-of-work decline matters as much as job counts do. A community with many low-hour, no-benefit positions can’t sustain the same local services or long-term investments as one with steady unionized employment. That mismatch between employment quantity and employment quality has been a quiet contributor to the Midwest’s difficulties. It also complicates policy responses, because job creation alone doesn’t fix job stability.

8. Brain drain: the best and brightest leaving to survive

Over 25 years, a steady stream of young, educated people left Midwestern towns for coastal metros and Sun Belt cities that offered growth, culture, and higher pay. That out-migration didn’t just reduce population; it removed teachers, entrepreneurs, and civic leaders who could have driven local renewal. Small towns lost not only workers, but the future mayors, business owners, and volunteers who sustain civic life. When young adults don’t come back, local institutions age and often fail to adapt to new economic realities.

Efforts to attract returnees — through tax credits, startup grants, or lifestyle marketing — have had mixed results. Many places underestimated how tied migration decisions are to networks, amenities, and perceived opportunity, not just salary. Fixing brain drain requires creating a credible pathway for careers and meaningful cultural life, which is expensive and politically difficult. Without that, demographic decline becomes structural rather than cyclical.

9. Climate and weather shocks: floods, droughts, and agricultural stress

Across the Midwest, more extreme weather — from historic floods to episodic droughts — has increased costs for farmers and municipalities alike. Flooding damages crops, erodes soil, and forces expensive rebuilds of levees, roads, and bridges, while erratic growing seasons complicate planning. Those shocks compound existing financial stress: when a farmer or town takes a climate hit, credit dries up and recovery can take years. The economic fallout isn’t evenly distributed, which deepens regional disparities and makes targeted recovery harder.

Climate impacts also influence migration and insurance markets, making some areas less attractive for investment. Local governments find themselves paying more for emergency responses while having less tax revenue to plan ahead. That squeezes long-term infrastructure projects and erodes community confidence in a stable future. The upshot is that climate volatility has become a significant driver of economic fragility in the region.

10. Aging infrastructure and public-service collapse

Many Midwestern towns face aging roads, bridges, water systems, and underfunded schools that make everyday life harder and investment less likely. Deferred maintenance accumulates like compound interest: small problems become emergency-level crises that are far more expensive to fix. When residents experience boil-water notices, unsafe bridges, or dilapidated libraries, it undermines civic pride and makes retention of residents — especially young families — more difficult. These failures feed a negative feedback loop between declining tax bases and rising repair costs.

Fixing infrastructure requires upfront capital, political will, and long-term planning — ingredients often missing in smaller jurisdictions. Grants and federal dollars can help, but they often require matching funds or expertise local governments lack. The net effect is slow-moving deterioration that silently lowers quality of life and economic competitiveness. That hidden erosion is part of why recovery feels so much harder than a one-off stimulus would suggest.

11. Political fragmentation and the policy gaps that followed

Over the last quarter-century, political polarization and fragmented governance made coordinated regional responses harder to organize. State and local leaders sometimes pursued competing visions — or no vision at all — leaving counties to fend for themselves with limited budgets. The result was a patchwork of policies that often failed to address long-term structural problems like workforce retraining, broadband, and housing. That gap between need and coherent strategy turned solvable problems into generational ones.

To reverse these trends requires long-term commitments across party lines, and an acceptance that short-term fixes won’t rebuild civic life. It also means aligning federal, state, and local resources in ways that respect local conditions while tackling structural gaps at scale. Without that alignment, many Midwestern places risk becoming footnotes in someone else’s growth story rather than active participants again.

This post Midwest 25-Year Collapse: The Timeline Nobody Wanted to Accept was first published on American Charm.