1. Uncle Sam

Uncle Sam feels like he’s been around since the Revolutionary War, but he’s actually a War of 1812 creation. The name came from Samuel Wilson, a meat packer in New York who supplied barrels to the U.S. Army. Stamped with “U.S.,” the barrels got nicknamed “Uncle Sam’s,” and the cartoon character emerged later. By the late 1800s, political cartoonists had cemented him into American culture.

The finger-pointing recruiting poster from World War I is what really made Uncle Sam iconic. Today, people treat him as a timeless personification of the government. But he was born out of a practical supply job and later inflated into a national mascot. The leap from meat barrels to global propaganda icon is a perfect example of history rewriting itself.

2. The Bald Eagle

Most people see the bald eagle as a timeless symbol of American freedom, but the choice was more practical than sentimental. When the founders picked it in 1782, they were impressed by its native range and powerful look, not necessarily any deep meaning. Ironically, Benjamin Franklin thought the eagle was lazy and cowardly compared to the turkey. He even argued the turkey was a “more respectable bird” for representing the nation.

Today, the eagle is seen as noble and proud, soaring above the land as a guardian of liberty. But originally, it was more about appearances than ideals. The symbolism we attach to it now grew over time, rather than being there from the start. That gap between intention and perception shows how history shapes our icons.

3. The Liberty Bell

The Liberty Bell is often thought of as the bell that rang on July 4, 1776, to mark independence. In reality, it never rang that day at all. The famous crack likely formed much later, sometime in the 19th century. Its status as a “patriotic” relic was largely invented by abolitionists in the 1800s, who saw its inscription about liberty as aligning with their cause.

That’s when the bell started traveling around the country as a kind of mobile symbol of freedom. It became tied to independence retroactively, not through original use. Americans today still flock to see it as a literal piece of 1776, but that’s not really accurate. What we honor is more myth than history.

4. The Gadsden Flag

The yellow “Don’t Tread on Me” flag is often waved as a broad symbol of freedom and rebellion. Its origin, though, was very specific: it was created by Christopher Gadsden in 1775 as a naval flag for the Continental Marines. It wasn’t meant to represent all patriots, but rather the early fight against Britain. At the time, the rattlesnake was seen as uniquely American, fierce, and defensive.

Today, the flag has been adopted by a wide range of political movements, often far removed from its original meaning. It’s become a catch-all banner for resistance, sometimes even in ways that contradict the founding ideals. The modern baggage attached to it would be unrecognizable to Gadsden himself. It’s a clear case of a historic emblem being reinvented by each generation.

5. The Statue of Liberty

Most people see Lady Liberty as a monument to American independence, but she wasn’t built with that in mind. France gave it to the U.S. in 1886 to celebrate the friendship between the two countries. The statue was originally meant to commemorate the end of slavery after the Civil War, not immigration or generic liberty. Early versions even included broken chains that were much more prominent.

Over time, though, Ellis Island’s proximity made her a symbol of welcoming immigrants. That association is now her most powerful legacy, overshadowing the original intent. People think of her as timeless, but her meaning has evolved dramatically. What started as an abolitionist gesture is now a broader message of hope.

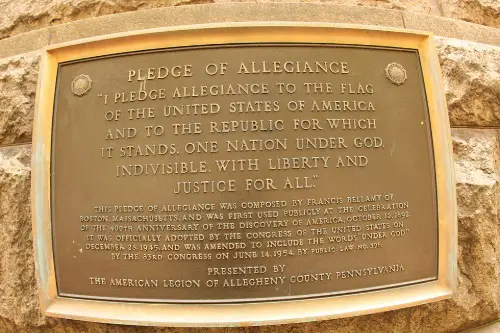

6. The Pledge of Allegiance

Many assume the Pledge of Allegiance dates back to the founding era, but it was actually written in 1892. It was part of a campaign to promote national unity, especially among schoolchildren. The original version didn’t even include the words “under God.” That phrase was only added in 1954 during the Cold War.

What feels like an ancient tradition is actually relatively new. It reflects more about 20th-century anxieties than about the Revolution. For generations of Americans, though, it’s become inseparable from patriotism. The layers of meaning built over time show how easily traditions can be reimagined.

7. Fireworks on the Fourth of July

People love fireworks as a literal representation of the “rockets’ red glare” from the national anthem. But the tradition started simply because John Adams wrote in a letter that Independence Day should be celebrated with “bonfires and illuminations.” Cities in the 1770s already used fireworks for festivals, so they carried that over. The booming skies were less about military might and more about spectacle.

Today, fireworks feel like they’re tied directly to the Revolution, but that wasn’t the original case. They’ve grown into an unofficial requirement of the holiday. Most Americans don’t realize how much the tradition is about festive celebration rather than historical accuracy. It’s patriotic, but more by habit than by origin.

8. The Liberty Tree

The Liberty Tree sounds like it was some grand, official symbol of the Revolution. In truth, it was just one elm tree in Boston where colonists gathered for protests. The Sons of Liberty used it as a meeting spot, and over time it became famous. When the British cut it down, colonists memorialized it as a martyr of sorts.

Other towns copied the idea and planted their own “Liberty Trees,” giving the impression of a widespread tradition. But its roots (literally) were local, not national. The modern romanticizing of it as a universal patriotic symbol oversimplifies the story. It’s a reminder that even ordinary landmarks can be elevated by history.

9. Mount Rushmore

Mount Rushmore is seen as a natural shrine to America’s founding ideals. What most people don’t realize is that it was originally intended to boost South Dakota tourism. Sculptor Gutzon Borglum picked the presidents to appeal to national pride, but the project was rooted in economics. On top of that, it was carved into land sacred to the Lakota Sioux.

The monument is often treated as an ancient symbol of unity, yet it’s less than 100 years old. Its placement on contested land makes its meaning complicated. To many, it represents both national glory and unresolved injustice. That duality isn’t reflected in the simplified patriotic narrative most Americans learn.

10. “Yankee Doodle”

“Yankee Doodle” is sung as a patriotic anthem, but it started as a song mocking Americans. British troops used it to ridicule colonial soldiers as unrefined and foolish. The “stuck a feather in his cap and called it macaroni” line was basically calling them wannabe aristocrats. Colonists, in a clever twist, adopted the song as their own rallying cry.

That reversal turned an insult into an anthem of defiance. Today, the mocking roots are largely forgotten, replaced with pride. Most people sing it without knowing its sarcastic origins. It’s a perfect example of how symbols can be reclaimed.

11. The National Anthem

“The Star-Spangled Banner” is embraced as a song celebrating American freedom. But Francis Scott Key’s lyrics were written during the War of 1812, not the Revolution. They were also originally paired with a British drinking song called “To Anacreon in Heaven.” The association with independence only came later when it was adopted in 1931.

For decades, other songs like “America the Beautiful” were just as popular candidates for the anthem. The eventual choice was more political than inevitable. Today, it feels like the anthem was born with the country itself, but that’s not true. Its patriotic aura was built through repetition, not origin.

12. The Washington Monument

The Washington Monument is treated as a timeless memorial to America’s first president. But construction was messy, starting in 1848 and halting for decades due to funding issues and the Civil War. When it finally resumed, stone from different quarries was used, creating the two-toned effect still visible today. The monument we see wasn’t completed until 1884.

The idea of it being a seamless tribute is more myth than fact. The delays reflected real divisions and struggles in the country. What we admire now as a simple symbol of unity was anything but during its creation. Its history is a reminder that even monuments carry the marks of conflict.

This post 12 “Patriotic” Symbols Americans Use That Don’t Mean What People Think was first published on American Charm.