1. Bloodletting Could Cure Almost Anything

Early American doctors believed that many illnesses were caused by an imbalance of bodily humors. To fix this, they often used leeches or lancets to drain blood from patients. It was common to think that removing “bad blood” could treat everything from fever to depression. People actually sought out physicians just for this practice, convinced it was essential to good health.

Even George Washington reportedly underwent bloodletting treatments. Physicians would sometimes remove up to half a pint of blood at a time, which could leave patients weak or dizzy. While the practice seems extreme now, it dominated medical thinking for centuries. The logic made sense to them: if the body was “too full,” draining it would restore balance.

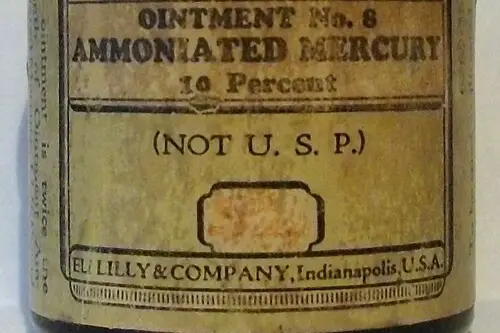

2. Mercury as Medicine

Mercury was used to treat a variety of conditions, most famously syphilis. Early Americans believed that the toxic metal could purge harmful substances from the body. They applied it as ointments, swallowed it in pills, or inhaled its vapors, often without realizing the dangers. Despite its toxicity, mercury-based remedies were seen as powerful medicine.

Patients sometimes developed severe side effects, including tremors and tooth loss, but that didn’t always stop physicians from prescribing it. They thought visible physical reactions were a sign the medicine was “working.” In a time when few treatments existed, people were willing to risk the side effects for a chance at a cure. It was a classic case of desperate times calling for desperate measures.

3. Tobacco as a Cure-All

Tobacco wasn’t just for smoking—it was considered a legitimate medical treatment. Colonists believed it could treat headaches, toothaches, and even more serious diseases like plague. Snuffing or smoking tobacco was thought to expel toxins from the body, while poultices made from the leaves were applied to wounds. Everyone from physicians to apothecaries promoted its use for almost every ailment.

Some doctors even prescribed it for children, thinking small doses could improve their health. People observed temporary relief, which reinforced the belief that tobacco had healing powers. While we now know nicotine is addictive and harmful, it was a cornerstone of early American medicine. For them, the immediate effects were more convincing than long-term harm.

4. Purging and Vomiting as Therapy

Purging the body with laxatives or inducing vomiting was a common remedy. Physicians believed illnesses originated from harmful substances accumulating in the stomach or intestines. By clearing out the “bad humors,” patients were thought to regain balance and health. Herbal concoctions were popular, sometimes made with strong and unpleasant ingredients.

It wasn’t unusual for patients to be subjected to multiple purges in a single day. The relief they felt afterward, even if temporary, seemed to validate the treatment. Doctors considered visible results a sign of efficacy, regardless of the underlying science. To them, a dramatic reaction meant the medicine was powerful and effective.

5. Animal Parts as Medicine

Many early remedies included parts of animals, from snakes to beavers. People believed that consuming or applying animal parts could transfer the creature’s strength or vitality to the patient. Snake skins might be used for skin conditions, while beaver castoreum was applied for fevers. This practice mixed superstition with the limited biological knowledge of the time.

The use of animal ingredients was also tied to the doctrine of signatures—the idea that a plant or animal’s characteristics indicated its healing potential. For instance, a liver-shaped herb might be used to treat liver problems. Early American doctors genuinely thought they were helping patients by harnessing nature’s power. It was a creative, if questionable, approach to medicine.

6. Quack Devices and Magnetic Healing

Magnetism was believed to influence health and cure illnesses. Some practitioners used iron rods, lodestones, or special “magnetic” devices on patients. They claimed these could realign bodily fluids or spirits, restoring balance. The allure of these methods was strong because they offered hope for conditions that had no other remedy.

Patients reported feeling relief, sometimes from placebo effect, which reinforced the belief in magnetism. These treatments were often expensive and sold as cutting-edge technology. Even respected physicians dabbled in magnetic therapy. It was a blend of science curiosity and wishful thinking in an era of limited options.

7. Snakes, Spider Webs, and Other Creepy Crawlers

Spider webs, snake venom, and other creepy creatures were commonly used as treatments. People applied them to wounds or ingested them to treat infections. They believed that parts of these creatures carried potent healing properties. This practice was partly inherited from European traditions and adapted in colonial America.

Spider webs, for example, were used to stop bleeding, and snake oil was applied for joint pain. The methods might seem disgusting today, but they often offered mild antiseptic effects or placebo benefits. The symbolic connection between the creature and the ailment guided these remedies. It’s an early example of “folk science” in everyday medicine.

8. Mercury and Lead Paints as Internal Medicine

Some physicians used substances like lead or mercury internally, thinking their toxic properties could drive out disease. Small doses were considered therapeutic, especially for conditions like constipation or infections. People applied these metals in ointments or ingested them as powders. The rationale was that dangerous substances could combat illness if carefully administered.

Unsurprisingly, the side effects were severe, sometimes causing poisoning or death. Yet doctors continued prescribing them, convinced of their efficacy. The lack of understanding about heavy metals’ toxicity allowed these treatments to persist. Patients often trusted that doctors knew best, even at great personal risk.

9. Snake Oil for Everything

Snake oil wasn’t just a metaphor for fraud—it was a widely used remedy. Early Americans believed that oils from snakes could ease inflammation, heal wounds, and even cure internal diseases. Salesmen and physicians alike promoted it as a miracle medicine. Its reputation grew because it seemed to help minor ailments, even if just through placebo effects.

The effectiveness was often anecdotal, and recipes varied widely, sometimes containing other herbs or fats. People accepted the risks because alternatives were limited and often equally strange. Snake oil exemplifies the mix of hope, tradition, and improvisation in early medical practice. It became a symbol of medicine’s experimental nature in the colonies.

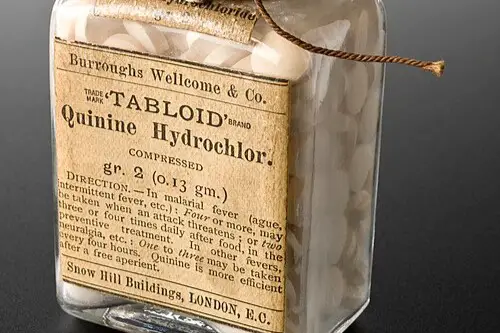

10. Quinine from Cinchona Bark

Quinine, derived from cinchona bark, was one of the few scientifically effective remedies. Early Americans used it to treat malaria, often mixed with water or wine. While the medicine worked, dosing was tricky, and it could be bitter or toxic if used improperly. It stood out because it had real physiological effects, unlike many other remedies of the time.

Doctors relied on it heavily in regions where malaria was common. It was an example of a treatment that combined observation and tradition. Its success likely strengthened confidence in plant-based remedies overall. People began to see that some natural substances could actually save lives.

11. Snail Slime and Other Odd Topicals

Topical treatments often included snail slime, onion poultices, or even animal fat. People applied them to wounds or skin conditions, believing they promoted healing. The logic was sometimes symbolic—like using snail slime for slow-healing wounds. These remedies were surprisingly common in households and apothecaries.

While the effectiveness was limited, some treatments provided mild antibacterial or soothing properties. Early Americans were experimenting with whatever substances were at hand. It reflects a creative, if not always scientifically sound, approach to medicine. People tried to make the best of what nature offered.

12. Mercury Pendants and Amulets

Some believed that wearing mercury in pendants or carrying charms could prevent disease. The idea was that mercury’s toxic properties could ward off evil spirits or infection. These amulets were worn around the neck or carried in pouches for constant protection. It was a mix of superstition, preventive medicine, and desperation.

Even educated people sometimes embraced these charms, seeing them as harmless if nothing else. They reinforced the idea that health could be influenced by both physical and mystical means. It shows how intertwined medicine and belief were in early America. For many, hope and ritual were as vital as any treatment.

This post 12 Strange Beliefs That Guided Early American Medicine was first published on American Charm.