1. The Golden Arches of McDonald’s

Americans see the Golden Arches and instantly think of burgers, fries, and childhood road trips. But those arches weren’t even meant to be iconic—they were originally a design quirk to make the buildings more visible from the highway. The company leaned into it, and suddenly a basic architectural feature became shorthand for fast food itself. It was luck that the public attached such deep meaning to something so simple.

Today, the arches are one of the most recognized logos worldwide, but they didn’t start with that intent. The marketing team just realized people remembered the symbol and doubled down. Without that recognition, McDonald’s could have been just another roadside diner. Sometimes all it takes is a shape that sticks in the brain.

2. The Coca-Cola Santa Claus

Americans love to credit Coca-Cola for “inventing” the modern image of Santa Claus. In reality, Coca-Cola just happened to ride a wave of imagery that was already floating around in magazines and illustrations in the early 20th century. Their 1930s ads with a jolly, red-suited Santa cemented the look, but they didn’t invent him. They were just lucky enough to have the advertising power to make him mainstream.

That stroke of marketing genius made Coca-Cola synonymous with Christmas. Imagine the timing: soda, which you wouldn’t expect to be a holiday drink, became part of festive traditions. Coke didn’t set out to reshape holiday culture—they just nailed the vibe and never let go. It’s a prime example of stumbling into cultural influence.

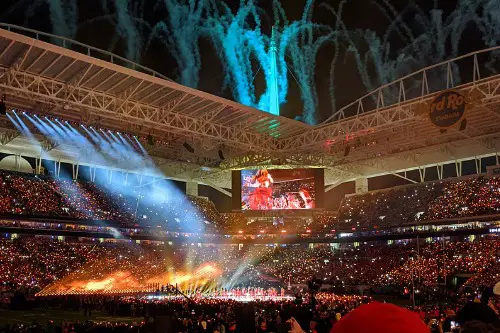

3. The Super Bowl Halftime Show

The halftime show is treated like a cultural Super Bowl within the Super Bowl, but it wasn’t always that way. In the early years, halftime was filled with marching bands and filler entertainment that people mostly ignored. It wasn’t until the early 1990s, when big-name stars like Michael Jackson were booked, that it exploded into the spectacle we know today. Timing and TV viewership trends did most of the work, not some master plan.

Now, advertisers spend millions to associate their brands with it, and fans argue about the best performances for decades. But the truth is, the NFL just stumbled onto the formula at the right moment. They leveraged the platform and turned it into something “iconic” without realizing they were creating an event bigger than the game for some people. It’s iconic because of momentum, not foresight.

4. Levi’s Blue Jeans

Blue jeans are considered the quintessential American fashion statement. Levi Strauss originally designed them as durable workwear for miners in the 1870s, not a style item. They became iconic only when Hollywood rebels like James Dean and Marlon Brando wore them in the 1950s, fueling the connection to coolness and rebellion. That wasn’t Levi’s plan—it was a cultural coincidence.

Today, Levi’s markets itself as the “original” jeans brand that shaped fashion. But the truth is, it could have been any denim brand with enough visibility in pop culture. Hollywood did the heavy lifting in turning work pants into a symbol of freedom. Levi’s just happened to be the name on the label when the trend took off.

5. Apple’s White Earbuds

Those little white earbuds from Apple became a status symbol in the 2000s. Apple leaned on slick iPod ads showing silhouettes dancing with the earbuds glowing in white, and suddenly, headphones weren’t just headphones. The funny part is, the white design was mostly a way to make the product stand out visually in marketing. People mistook that visibility for “iconic design.”

Apple couldn’t have predicted how much those ads would shape culture. White cords dangling from your ears became shorthand for being part of the iPod generation. Other brands sold equally good or better headphones, but they didn’t have the luck of a perfectly timed ad campaign. That accident of marketing made Apple look cooler than anyone else.

6. The Starbucks Red Cup

Every holiday season, people wait for Starbucks to drop its red cups. The company treats it like a tradition, but the first red cup in the 1990s was just a seasonal gimmick. Customers latched onto it, sharing photos and treating it as a marker that the holidays had officially begun. Starbucks wasn’t expecting to create a cultural countdown.

Now, it’s a marketing juggernaut that sparks debates and even controversies every year. The cups themselves are just cups—paper, disposable, gone in minutes. But the timing and public reaction made them iconic symbols of the season. It was a lucky accident that people turned a marketing prop into a ritual.

7. Budweiser’s Clydesdales

Clydesdales weren’t originally tied to beer or American identity. Anheuser-Busch first used them in the 1930s to celebrate the repeal of Prohibition, and they just stuck around as a quirky mascot. Over the years, commercials featuring the horses tugged at emotions and nostalgia, making them part of the “classic American” brand image. It was less about strategy and more about luck that audiences loved them.

Today, seeing a Clydesdale makes people think “Budweiser,” even if they don’t drink beer. The horses represent tradition and Americana in a way no one could have scripted. If those early ads had flopped, Budweiser’s icon might have been something completely different. Instead, sheer chance turned draft horses into cultural celebrities.

8. Route 66

Route 66 is often romanticized as the “Mother Road” of America. But when it was first established in 1926, it was just another highway designed to connect rural communities to cities. Its mythic status came later, thanks to songs, TV shows, and travel marketing campaigns in the mid-20th century. Without pop culture’s help, it would’ve been just another road number.

Americans now see Route 66 as a symbol of freedom and nostalgia. But most of that is manufactured—marketing gave the highway its legend. Other roads could’ve had the same fate if someone had written a catchy song about them. Route 66 just got lucky with timing and storytelling.

9. Monopoly Board Game

Monopoly is billed as America’s board game, but its origins are messier than most people realize. It was actually based on a game called “The Landlord’s Game,” designed to critique capitalism. Parker Brothers bought it, rebranded it, and turned it into a celebration of ruthless competition. The shift was more luck than genius marketing—people enjoyed the fun of play-acting as tycoons.

Now, Monopoly feels like an American institution, with endless special editions and tournaments. But the truth is, it was a rebranded knockoff that happened to hit at the right cultural moment. If people had leaned more into its original message, it might never have become popular. Instead, a marketing spin flipped the narrative and made it iconic.

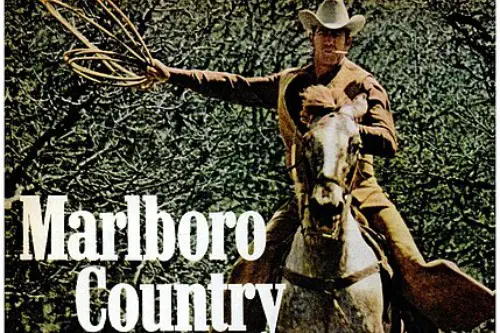

10. The Marlboro Man

The Marlboro Man is one of the most recognized advertising figures in history. What’s wild is that Marlboro originally marketed its cigarettes to women as “mild as May.” Sales were tanking until they pivoted to rugged cowboy imagery in the 1950s. That lucky switch rebranded the product entirely and made it look masculine and strong.

The campaign struck a chord and made Marlboro the world’s top-selling cigarette brand. But it wasn’t some long-term plan—it was a last-ditch effort that just happened to work. Without that cowboy imagery, Marlboro might not even exist today. The “iconic” part came from desperation meeting cultural timing.

11. Times Square’s Ball Drop

New Year’s Eve in Times Square feels like a time-honored American tradition. But the ball drop was originally just a publicity stunt for The New York Times in 1907. The newspaper wanted attention for its new building and used the glowing ball as a spectacle. People loved it, and the ritual stuck by sheer force of repetition.

Today, millions watch the ball drop every year as if it were always meant to be. But it wasn’t destiny—it was clever marketing that snowballed into a cultural must-do. If it hadn’t worked that first time, New Year’s Eve might be celebrated very differently. Instead, luck turned an advertisement into tradition.

12. Mount Rushmore

Mount Rushmore is treated like a sacred American landmark, but its origins are far more pragmatic. It was conceived in the 1920s as a way to attract tourists to South Dakota. The choice of presidents wasn’t based on a deep national consensus—it was more about who would draw attention. The “iconic” nature came later, as people assigned meaning to it.

Now, it’s one of the most visited monuments in the U.S., but its fame comes from marketing, not destiny. Tourism campaigns pushed it into the spotlight, and Hollywood helped by using it as a dramatic backdrop. If not for those efforts, it might’ve been dismissed as a quirky roadside attraction. Its iconic status is really just a lucky branding win.

This post 12 Things That Americans Call Iconic—But Were Just Lucky Marketing was first published on American Charm.