1. Florida

Florida’s Department of Education has recently made headlines for altering how slavery is taught in public schools, according to Antonio Planas of NBC News. New standards suggest that enslaved people “developed skills” that could be used for their “personal benefit,” a phrasing that many historians and educators find deeply misleading. Critics say this reframes the brutality of slavery in a way that downplays its horrors. The changes are already influencing textbook publishers to revise content.

This shift isn’t just about language—it’s about the entire lens through which students view American history. Florida’s guidelines are shaping textbooks used by other states too, due to its massive buying power. That means the ripple effects could extend far beyond state borders. It’s not just what’s being said, but what’s being left out entirely.

2. Texas

Texas has long been a textbook titan, but its State Board of Education recently approved standards that minimize references to the Ku Klux Klan and the Civil Rights Movement, Minyvonne Burke and The Associated Press told NBC News. Some proposals even aimed to rename slavery as “involuntary relocation.” Although this language was eventually revised after public backlash, it highlighted how close the board came to reframing historical atrocities. Texas textbooks often serve as templates for others nationwide.

That’s why when Texas shifts, the entire country feels it. These changes don’t always remove content—they sometimes bury it under euphemisms. Students are learning a version of history that softens systemic racism and erases context. That makes critical thinking about past injustices much harder to develop.

3. Oklahoma

After passing legislation that limits discussions of race and gender in classrooms, Oklahoma teachers are finding themselves second-guessing what they can legally say, according to Tom Ferguson of Fox 25. House Bill 1775, passed in 2021, prohibits teaching that might make students feel “discomfort” due to race or sex. While the bill doesn’t explicitly ban historical facts, its vague language has had a chilling effect. Educators say they are afraid to teach even basic truths about Jim Crow laws or the Tulsa Race Massacre.

Ironically, that massacre happened in Oklahoma, and yet many students still don’t learn about it. The risk of losing their jobs has made some teachers avoid topics that were once staples of honest education. The law effectively sanitizes history rather than helping students grapple with its complexity. And that loss of nuance is spreading to the textbooks.

4. Tennessee

Tennessee’s curriculum guidelines now sidestep key topics like systemic racism, replacing them with generalized language about “diversity.” After passing laws that limit how racial history is taught, publishers adjusted textbook content to comply, according to Zane McNeill of Truthout. Instead of addressing historical inequities directly, textbooks now emphasize unity and patriotism. While that might sound nice, it can distort the context of important events.

For instance, references to Martin Luther King Jr. have been trimmed to focus more on his “American dream” message than his calls for economic justice. Civil rights coverage feels like a highlight reel, not a deep dive. By glossing over the roots of inequality, the textbooks offer a shallow version of the past. And that shapes how future generations understand justice and progress.

5. Georgia

In Georgia, history standards are shifting toward what officials call “positive framing.” That means highlighting America’s achievements while reducing focus on its mistakes. The Civil War, for example, is sometimes described in textbooks as being about “states’ rights,” with slavery treated as a secondary cause. Teachers say this framing omits key truths and waters down difficult conversations.

This isn’t about adding patriotism—it’s about removing hard truths. By rewording or skipping over historical realities, textbooks lose their power to teach empathy and critical thinking. Students end up memorizing dates without grasping their meaning. And that can make history feel more like mythology.

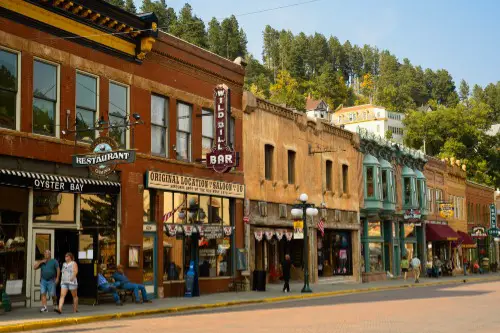

6. South Dakota

South Dakota’s Department of Education proposed standards in 2022 that dramatically reduced Native American history content. This shocked educators, especially in a state with a significant Indigenous population. The proposed cuts removed almost all references to local tribes and their history post-European contact. After backlash, some content was reinstated—but not all.

The damage is already done in some classrooms. Teachers report being unsure of how much they’re “allowed” to include. That insecurity stifles honest storytelling, especially about treaties and tribal sovereignty. For Native students, it’s a painful erasure of their heritage.

7. North Carolina

North Carolina’s recent revisions to its social studies curriculum have made educators uneasy, particularly regarding race and colonialism. The new standards emphasize “American exceptionalism” and omit in-depth discussions of slavery and Indigenous displacement. Teachers are encouraged to focus on “civic responsibility” and “founding principles” instead. That shift makes it harder to address the darker sides of American history.

This change came after political debates that painted critical discussions as “divisive.” Now, students might leave school with a skewed understanding of how power and oppression have shaped the country. Even textbook publishers are editing chapters to align with these sanitized narratives. The result is a version of history that feels incomplete—and in some cases, inaccurate.

8. Missouri

Missouri lawmakers have pushed for limits on “critical race theory,” even though it’s rarely part of K-12 education. The backlash has led to changes in what textbooks include about racial inequality. Some schools are using materials that avoid discussing redlining, mass incarceration, and voter suppression. Instead, racial disparities are often explained with vague references to “historical challenges.”

This oversimplification removes the systemic nature of these problems. Without context, students may not understand how past policies affect people today. And when textbooks ignore this, it shapes an entire generation’s perception of justice. Missouri’s changes might look small, but they ripple outward.

9. Kentucky

In Kentucky, textbook committees are under pressure to avoid what some politicians call “divisive topics.” That means less focus on labor history, civil disobedience, and slavery’s economic legacy. The goal, apparently, is to keep content “balanced,” but in practice that often means neutralizing powerful stories. Students are learning a version of history stripped of its emotional and political weight.

One teacher described how their district removed materials on the Highlander Folk School, a crucial site in civil rights organizing. These omissions aren’t just academic—they’re cultural. They rob students of the chance to see how ordinary people have driven social change. And they suggest that struggle and protest are somehow un-American.

10. Arkansas

Arkansas has passed laws requiring history instruction to avoid making students feel “guilt” over past events. This has led some districts to downplay or omit the history of segregation and school integration. The 1957 Little Rock Nine crisis—something that happened in Arkansas—is now discussed with less emotional depth in some textbooks. The state’s own pivotal moments are being flattened out.

This kind of revisionism does a disservice not just to students, but to the people who lived through these events. By removing emotional resonance, the story becomes abstract. Students learn names and dates, but not stakes. And that makes it easier to ignore the consequences of injustice.

11. Arizona

Arizona’s education board revised history standards in ways that limit how race and identity are discussed. This follows years of battles over ethnic studies programs, which were once banned outright. While some of those programs have returned, textbook content is still cautious. Complex topics like colonialism and cultural erasure are now presented more generally.

Some textbooks have removed entire units on Chicano history or Indigenous resistance. The result is a curriculum that doesn’t reflect the diverse backgrounds of its students. Teachers are left to fill in the gaps if they can. But many say they don’t feel supported when they try.

12. Indiana

Indiana has begun using new textbook guidelines that favor “traditional values” and downplay what they call “controversial” content. That includes sections on immigration, protest movements, and LGBTQ+ history. Several textbooks have removed references to the Stonewall Riots and Harvey Milk. Instead, diversity is mentioned only in passing.

This narrowing of scope leaves out major milestones in American civil rights. Students may never learn how LGBTQ+ people have fought for legal protections and social change. And that erasure shapes not just understanding, but identity. Indiana’s changes are quiet—but deeply impactful.

13. Idaho

Idaho lawmakers passed a bill banning “critical race theory” and defunding programs that promote it. In the aftermath, publishers revised textbook content to steer clear of systemic racism or white privilege. Lessons that once explored inequality in housing and education are now more focused on individual responsibility. The shift is subtle but profound.

Without systemic context, students may believe that disparities are personal failures rather than historical outcomes. That makes it harder to have honest, solution-focused conversations. Educators say the pressure is making them hesitant to engage with real-world issues. And textbooks are following that lead.

14. Mississippi

Mississippi, with its deeply rooted civil rights history, has recently adopted curriculum revisions that emphasize “heritage” over conflict. Textbooks now include more content on Confederate leaders framed as figures of “regional importance.” At the same time, chapters on lynching and voter suppression have been shortened or cut entirely. This framing undermines the scale of the struggle Black Americans faced.

Students might hear about the Civil Rights Movement but not understand what made it necessary. That leaves them with a fragmented view of history. It also dishonors those who fought for justice. In a state where so much happened, the silence is deafening.