1. The Frontier Was Empty Before Settlers Arrived

One of the most persistent myths about the American frontier is that it was a vast, untouched wilderness waiting for pioneers to “discover.” In reality, Indigenous nations had lived there for thousands of years, shaping ecosystems through controlled burns, trade networks, and seasonal migrations. By the time Europeans arrived, North America was already a complex web of communities and territories. The myth of emptiness was convenient—it justified expansion and displacement by pretending no one was being displaced.

Historians keep pushing back against this idea because it erases Indigenous history and agency. Archaeology and oral traditions reveal thriving civilizations, from the Mississippian mound builders to the Pueblo peoples of the Southwest. The “empty land” narrative also feeds the romanticized image of rugged individualism that defines much of American mythology. But the truth is, settlers were moving into someone else’s home, not a blank slate.

2. Cowboys Were Mostly White

Hollywood made the cowboy a white, stoic loner, but the real frontier was far more diverse. Up to a third of working cowboys were Black, Mexican, or Indigenous, and many came from formerly enslaved backgrounds after the Civil War. These men worked the same brutal jobs—herding cattle, breaking horses, and facing the elements—with little recognition. The image of the white cowboy wasn’t an accident; it was crafted later to fit a cleaner national story.

Historians emphasize this point because it changes how we see the West itself: not as a monoculture, but as a crossroads. The cattle trails and ranches were melting pots of language and culture. Ignoring that diversity means missing what made the frontier dynamic and, frankly, real. The myth endures because Hollywood made it iconic—but history makes it interesting.

3. The Frontier Ended in 1890

When the U.S. Census Bureau declared the frontier “closed” in 1890, people took it literally—as if a line had been crossed and the story was over. But settlement, conflict, and expansion continued well into the 20th century, especially in Alaska and parts of the Southwest. The “closing” was really just a bureaucratic milestone that made for a neat narrative. It didn’t match what was happening on the ground.

Historians keep revisiting this because the frontier never really ended—it evolved. People were still moving west, Native lands were still being seized, and industries like mining and oil were reshaping the landscape. The myth of a neat ending lets Americans package history into a tidy moral arc. Reality, as usual, is much messier.

4. Pioneers Traveled Alone in the Wilderness

It’s easy to imagine covered wagons plodding into the unknown, families braving danger without help. But most settlers traveled in organized groups, often following established trails with guidebooks, supply stations, and military protection. They weren’t wandering blindly; they relied on maps and, crucially, on Native guides who knew the land. The “lone family on the prairie” is more legend than fact.

This myth sticks because it flatters the American ideal of self-reliance. Yet, cooperation was the only way most people survived the journey. Wagon trains functioned like small communities, with rules, elected leaders, and shared labor. Independence made for better storytelling—teamwork just made for better odds.

5. Everyone Lived in Log Cabins

The log cabin is practically a national symbol, but it wasn’t the go-to frontier home everywhere. In the Great Plains, settlers used sod because trees were scarce; in the Southwest, adobe was the material of choice. Even where timber was abundant, cabins were often temporary shelters before more permanent homes went up. The romantic image of the cabin in the woods is more marketing than memory.

Historians highlight this because it shows how adaptable settlers were to their environments. Building materials weren’t about aesthetics—they were about survival. The one-size-fits-all image of a rustic log home flattens the regional variety of frontier life. Real homesteaders made do with whatever the land offered, not what later artists painted.

6. Gunfights Were an Everyday Occurrence

Popular culture loves the image of dusty main streets and dramatic duels at high noon. But in truth, frontier towns had fewer gunfights than many 19th-century Eastern cities. Most Western towns enforced strict gun control—firearms were often checked at the sheriff’s office or saloon door. The constant shootout trope owes more to dime novels than to daily life.

Historians point this out because it reshapes how we see the “Wild West.” While violence did exist, it was more likely in disputes over land or resources than random street showdowns. Law enforcement and local ordinances were surprisingly effective. The West was rough, yes, but not the nonstop war zone pop culture insists on.

7. Women Stayed Home and Kept Quiet

The frontier woman was far more than a background character to her husband’s adventures. Women ran farms, ranched cattle, ran businesses, and even ran for office in newly formed territories. The West’s fluid social structures gave them opportunities they often couldn’t find back East. In many places, women’s labor literally kept communities alive.

Historians push this narrative because it highlights the gender diversity of frontier roles. Women were homesteaders, teachers, and entrepreneurs who shaped the social and economic fabric of the West. States like Wyoming and Utah granted women the vote decades before the rest of the country. The idea of the passive frontier wife is not only wrong—it’s insulting to the women who built towns from dust.

8. The Frontier Was Lawless

The term “Wild West” suggests chaos, but most frontier towns had systems of order early on. Sheriffs, judges, and even informal committees kept things relatively stable. The myth of total lawlessness comes from a handful of infamous towns like Dodge City or Tombstone, which were exceptions, not the rule. In truth, settlers craved predictability as much as opportunity.

Historians revisit this myth because it feeds the notion that civilization was imposed from outside. In reality, law often emerged from within—local communities drafted rules and enforced them collectively. Violence did occur, but so did civic organization and public accountability. The West was never as anarchic as its reputation suggests.

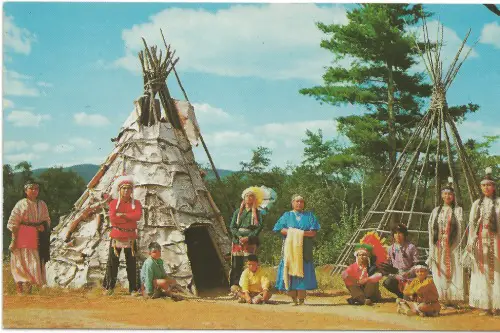

9. Native Americans Were a Single, Unified Group

In many frontier stories, Native Americans are portrayed as one monolithic force opposing “civilization.” But in truth, hundreds of distinct nations with different languages, governments, and alliances lived across North America. Some traded with settlers, others resisted, and many navigated complex diplomatic relationships in between. Reducing them to a single “enemy” oversimplifies centuries of history.

Historians stress this because it restores individuality to Native nations. The Sioux, Apache, and Cherokee, for instance, had vastly different cultures and experiences with colonial powers. Understanding that diversity changes the story from a binary struggle to a web of negotiations and conflicts. It’s not just more accurate—it’s more human.

10. The Gold Rush Made Everyone Rich

The California Gold Rush lures the imagination with glittering success stories, but most prospectors didn’t strike it rich. A handful of lucky miners hit major finds, while the majority barely covered their costs—or died trying. Those who made real money often sold supplies, ran boarding houses, or transported goods. The gold was often in someone else’s pocket.

Historians highlight this because it exposes the economic realities behind the myth. The Gold Rush fueled migration and industry, yes, but also exploitation, displacement, and environmental damage. It was more about risk and disappointment than overnight fortune. The dream was golden, but the reality was mostly mud.

11. The Frontier Was a Man’s World

Men dominate frontier mythology, but the gender balance was more nuanced than that. Frontier life required everyone’s labor, and communities couldn’t survive without women’s and children’s work. Women also played central roles in social organization, healthcare, and education. The idea of a male-only wilderness is mostly a cinematic invention.

Historians note that women’s influence extended into politics, religion, and reform. They founded schools, churches, and social clubs that stabilized frontier society. Many of the first suffrage movements began in western territories precisely because women were already vital community members. The “man’s world” image makes for good adventure stories—but bad history.

12. The Frontier Was All About Freedom

The idea of the frontier as pure freedom—limitless land and endless opportunity—is deeply woven into the American identity. But that freedom was often built on the unfreedom of others: Indigenous displacement, enslaved labor, and exploited immigrant workers. Expansion came with violence, inequality, and environmental loss. The open range wasn’t as open as the myth suggests.

Historians keep returning to this because it reveals the moral contradictions of the American story. The frontier did inspire resilience and creativity, but it also carried deep costs. Recognizing that tension doesn’t diminish the West—it makes it more honest. Myths make us feel proud; history makes us think.

This post 12 Myths About the Frontier That Historians Can’t Kill Off was first published on American Charm.