1. George Washington Had Wooden Teeth

We’ve all heard it: Washington had a full set of wooden teeth. The truth is, his dentures were made from materials like human teeth, animal teeth, and ivory, but never wood. He struggled with dental issues for most of his adult life, which is probably why stories about “wooden teeth” sounded plausible. Schools love the wooden teeth anecdote because it’s memorable and a little humorous.

The misconception likely started because his dentures stained over time, making them look wooden. Historians have examined surviving dentures and letters describing them, confirming the variety of materials. Washington even complained about how painful they were. This myth persists because it’s simpler and more visual than the complicated reality.

2. Thomas Jefferson Wrote the Declaration of Independence Alone

It’s common to say Jefferson single-handedly penned the Declaration of Independence, giving him near-mythical status. In reality, he was the principal author, but a committee of five, including John Adams and Benjamin Franklin, reviewed and edited his work. His drafts went through significant changes before Congress approved the final version. Schools often highlight Jefferson alone because it fits neatly into a hero narrative.

The myth glosses over the collaborative process that shaped the document’s final wording. Jefferson himself acknowledged the edits made by the committee in his letters. Understanding the teamwork involved paints a more accurate picture of the revolutionary process. It also shows that history isn’t just about one person’s genius—it’s about negotiation, compromise, and shared vision.

3. Benjamin Franklin Discovered Electricity with a Kite

Everyone remembers Franklin flying a kite in a thunderstorm to “prove” electricity exists. In reality, he never conducted the dangerous experiment exactly as pop culture imagines. Franklin’s experiments were safer and more controlled, focusing on demonstrating the electrical nature of lightning using a key and a Leyden jar. The kite story endures because it’s dramatic, visual, and easy to teach.

The myth oversimplifies his actual contributions to electrical science, which were extensive and methodical. Franklin wrote extensively about electricity, including the famous concepts of positive and negative charge. Teachers often use the kite story as a hook, even if it’s not historically precise. It’s a classic case of history getting “Hollywood-ized.”

4. John Adams and Thomas Jefferson Died on July 4, 1826, Exactly

This one sounds almost too perfect: two founding fathers dying on the 50th anniversary of the Declaration. While it’s true they both died on July 4, 1826, the coincidence is just that—a coincidence. Schools tend to romanticize it because it’s poetic and easy to remember. It creates a narrative of destiny that is much more compelling than random chance.

The truth is, neither Adams nor Jefferson had any idea they would die on that date. Letters from the period show their deaths were normal for people of their age. Historians caution against reading meaning into it, but textbooks often present it as symbolic. The story persists because it’s tidy and dramatic, perfect for storytelling in a classroom.

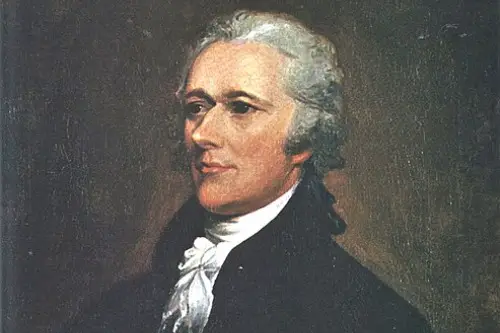

5. Alexander Hamilton Was Born Poor

Hamilton is often framed as the ultimate “rags-to-riches” story. While he did face hardships in his early life in the Caribbean, calling him “poor” oversimplifies the reality. He had access to some education and social connections that helped him rise quickly in America. Schools lean into this myth because it makes him relatable and inspirational to students.

Hamilton’s story is still impressive—he rose from modest circumstances to become a major political figure—but he wasn’t a destitute orphan. Letters show he received mentorship and support that were crucial for his education. Understanding these nuances gives a more accurate view of social mobility in colonial America. It also shows how luck, talent, and networks all mattered in shaping his path.

6. The Founding Fathers Were All Wealthy Landowners

It’s often taught that all the founders were rich plantation owners, which isn’t quite right. While many had property and social standing, figures like Franklin, Hamilton, and even Jefferson at certain points struggled financially. Some worked in trades, journalism, or law before amassing wealth. The myth simplifies history into a “rich guys made the country” story, which is easier to digest in textbooks.

In reality, the founders came from a variety of economic backgrounds. Their financial circumstances influenced their political views, including debates over taxation and federal power. Reducing them all to rich landowners ignores these complexities. Recognizing their diverse backgrounds paints a more accurate picture of early American society.

7. George Washington Was a Hero in Every Battle

We often imagine Washington as an infallible military genius. The truth is he lost more battles than he won during the Revolutionary War. His real skill lay in strategy, patience, and keeping the Continental Army together despite repeated defeats. Schools tend to emphasize his “heroic” image because it’s inspiring and patriotic.

Washington’s leadership was less about flawless execution and more about resilience. For instance, retreats and strategic losses helped him preserve his forces for eventual victory. Understanding this makes his achievements more impressive, not less—it shows perseverance under pressure. Myths of constant triumph obscure the reality of the long, grueling fight for independence.

8. The Founders Created the Constitution Quickly

Textbooks sometimes give the impression that the Constitution was drafted quickly and smoothly. In reality, it took four months of intense debate, compromise, and negotiation in Philadelphia. Delegates argued over representation, slavery, and the balance of power for hours on end. The “quick and decisive” version is easier to memorize and fits neatly into lesson plans.

The process included multiple drafts, backroom negotiations, and compromises that still affect American politics today. Misrepresenting this process glosses over how contentious and complex nation-building really was. Understanding the drawn-out nature of the convention shows that democracy is messy, slow, and often uncomfortable. Myths make it seem like the Constitution was handed down perfectly formed.

9. Thomas Jefferson Was Consistently Anti-Slavery

Jefferson is often presented as a moral opponent of slavery. In reality, he owned hundreds of enslaved people throughout his life and profited from their labor. He expressed conflicted views on slavery in writings but rarely took meaningful action to end it. Schools sometimes simplify his story to avoid grappling with this uncomfortable contradiction.

Jefferson’s legacy is complicated, balancing philosophical ideals with personal practices that were inconsistent with those ideals. He proposed gradual emancipation in theory but maintained the institution in practice. A nuanced teaching of Jefferson shows the gap between principle and action in early America. Oversimplifying him as “anti-slavery” erases these historical tensions.

10. Paul Revere Warned Everyone About the British Alone

The story of “one if by land, two if by sea” makes it seem like Revere single-handedly warned colonial militias. In truth, he was part of a network of riders, including William Dawes and Samuel Prescott. The message was spread collectively, not by a single dramatic ride. Schools love the Revere legend because it’s cinematic and easy to visualize.

The myth sidelines the other patriots who contributed to the effort. Contemporary records describe multiple riders coordinating to alert towns. Understanding this network underscores the collaborative nature of revolutionary action. The solo-hero narrative is much easier to teach than a web of connected riders.

11. The Founders Agreed on Everything

Textbooks sometimes imply that the founding fathers were united in their vision. In reality, there were fierce debates over federal power, representation, trade, and slavery. The differences among them led to the creation of political factions almost immediately. Schools often downplay conflict to present a smoother story of national unity.

Conflicts like Federalists vs. Anti-Federalists show how varied political philosophy was even among elite leaders. These debates shaped policies and institutions still in place today. Ignoring their disagreements creates a misleading picture of early American politics. Understanding the disagreements helps students see that compromise was central to the nation’s founding.

12. Betsy Ross Made the First American Flag

It’s a charming story: Ross sewing the first Stars and Stripes at Washington’s request. The historical evidence for this is thin, mostly family lore passed down generations later. The flag likely evolved over time with contributions from multiple people. Schools highlight Ross because her story adds a human and feminine touch to the founding narrative.

The myth reinforces the idea of individual “firsts” in history, which are rarely that simple. While Ross may have made flags, we don’t have primary sources confirming she created the official one. Teaching her story as fact distorts how symbols like the flag actually emerged. It persists because a single-person story is easier to remember and tell.

13. The Founders Were Perfectly Virtuous

We often teach the founders as morally exemplary, brave, and wise. In reality, they had personal flaws, contradictions, and biases. Some engaged in business dealings we would now consider unethical, others held prejudices that influenced policy. Schools simplify them into role models for civic virtue because it’s easier than discussing human complexity.

Understanding their flaws doesn’t diminish their achievements; it contextualizes them. Recognizing moral contradictions makes history richer and more relatable. It shows that influential figures can have positive impact despite personal shortcomings. The myth of perfect virtue is comforting but inaccurate.

14. The Founders Wanted a Democracy Like Today

Many students are taught that the founding fathers created a “democracy” as we know it now. In reality, they designed a republic with checks and balances, wary of direct democracy. Most feared mob rule and sought to limit popular influence on government decisions. Schools often use “democracy” loosely because it’s easier for students to grasp.

The distinction between a republic and a pure democracy was crucial to the founders’ thinking. Understanding this helps explain features like the Electoral College, Senate representation, and judicial review. Misrepresenting it oversimplifies early American political philosophy. Teaching the nuance shows that the system they built was intentionally cautious and complex.

This post 14 Myths About the Founding Fathers That Still Get Taught in Schools was first published on American Charm.