1. Paul Revere’s Midnight Ride

Ask most Americans and they’ll tell you Paul Revere rode alone, shouting, “The British are coming!” That version came from Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s famous poem, written decades after the actual event. In reality, Revere was one of several riders, and he never shouted the dramatic warning—it would’ve alerted British patrols. Instead, he spread the word quietly and was even captured for a time.

The legend of a lone hero was far easier to celebrate than a network of ordinary patriots doing the hard work of organizing. Longfellow’s version turned Revere into a symbol of brave individuality. The truth—that it was a team effort—felt less romantic. It survived because people wanted a storybook hero, not a community effort.

2. George Washington and the Cherry Tree

Everyone learns the story about young George Washington chopping down a cherry tree and confessing with, “I cannot tell a lie.” It’s a heartwarming tale that paints him as the ultimate symbol of honesty. But this story was completely fabricated by Mason Locke Weems, one of Washington’s early biographers. It caught on because it made Washington seem saint-like, especially for schoolchildren.

The real Washington was a complex man who owned enslaved people and made tough, sometimes ruthless, choices as a leader. The cherry tree myth survived because it was far easier to teach kids about honesty than to wrestle with moral contradictions. For generations, Americans wanted their first president to feel flawless. The truth, while more human, didn’t make for a clean moral lesson.

3. Betsy Ross Sewing the First Flag

The idea of Betsy Ross sewing the first American flag is a staple of history books. According to the story, George Washington himself brought her the design, and she suggested the now-famous five-pointed star. But historians have found no evidence this meeting ever happened. The story actually surfaced almost 100 years later, pushed by her descendants.

The myth stuck around because it gave Americans a relatable, maternal figure to credit with a national symbol. It was easier to picture one determined seamstress than a messy process involving committees and multiple designers. Plus, the story conveniently emphasized women’s contributions in a way that felt safe and apolitical. The uglier truth—that the flag’s origins were bureaucratic and disputed—wasn’t as inspiring.

4. Davy Crockett Died Fighting to the End at the Alamo

The legend of Davy Crockett swinging his rifle until his last breath is one of the most enduring Alamo stories. This version shows him as a fearless fighter who went down heroically. But eyewitness accounts suggest he may have surrendered and was executed by Mexican forces afterward. For many Texans, that detail was too humiliating to accept.

The myth of a last stand was easier to rally around. It turned Crockett into a martyr and the Alamo into a symbol of sacrifice. Admitting he might have surrendered complicated the narrative of bravery and defiance. The harsher version just didn’t fit the heroic script Texas wanted to tell.

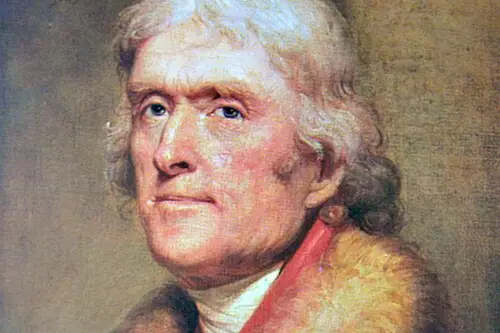

5. Thomas Jefferson and His “Pure” Enlightenment Ideals

Jefferson is remembered as the eloquent author of “all men are created equal.” That line has been repeated as the bedrock of American ideals. Yet Jefferson enslaved hundreds of people and profited from their labor his entire life. He even fathered children with Sally Hemings, an enslaved woman he owned.

The myth of Jefferson as a spotless philosopher survived because America wanted to cling to his words without confronting his contradictions. It was more comfortable to celebrate the Declaration than to reckon with the hypocrisy behind it. The ugliness of his personal life didn’t fit the marble-statue image. So the myth of Jefferson as a purely noble thinker won out.

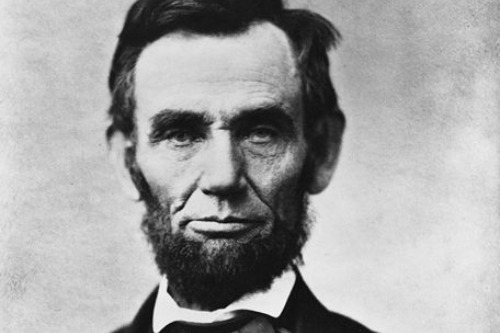

6. Abraham Lincoln as the Great Emancipator

Lincoln is remembered as the man who freed the enslaved with one stroke of his pen. But the Emancipation Proclamation was a carefully calculated military move, freeing only those enslaved in Confederate states still in rebellion. Lincoln’s top priority was preserving the Union, not abolition. He even considered colonization plans to send freed people abroad.

The myth of a single savior freeing millions was far simpler than the messy political reality. Americans wanted a clear hero who embodied freedom, not a cautious politician responding to pressure. That narrative was easier to celebrate during wartime and afterward. The harsher truth—that enslaved people fought for their own freedom—got overshadowed.

7. Christopher Columbus “Discovering” America

For centuries, children learned that Columbus discovered America in 1492. The myth made him a fearless explorer who brought civilization to the New World. In reality, people had lived in the Americas for thousands of years, and the Vikings had arrived centuries earlier. Columbus’s voyages also launched centuries of violence, enslavement, and disease.

The sanitized version survived because it was easier to celebrate progress than confront genocide. Columbus became a stand-in for bravery and exploration. Schoolbooks erased the brutality to create a neat founding myth. The uglier side didn’t fit the story of American greatness.

8. Pocahontas and John Smith’s Love Story

Hollywood turned Pocahontas into a young woman who fell in love with John Smith, bridging two worlds. But in reality, Pocahontas was around 11 or 12 when she met him, and Smith himself exaggerated much of their interaction. Her later marriage to John Rolfe was political, not romantic. She died in England at just 21, far from home.

The myth of a love story was more palatable than the truth of colonial exploitation. It turned conquest into romance and gave Americans a fairy-tale narrative. The real Pocahontas’s life reflected cultural erasure and manipulation. But that was too grim to put into storybooks.

9. General Custer’s “Glorious Last Stand”

The story goes that George Armstrong Custer made a brave last stand at the Battle of the Little Bighorn, fighting valiantly with his men against overwhelming odds. For years, paintings and dime novels showed him in heroic poses, pistol raised as his troops fell around him. But eyewitness accounts suggest chaos, poor leadership, and perhaps even panic defined the battle. Many of his men died quickly, not gloriously.

The myth stuck because the U.S. Army and the public needed a tragic hero, not a reckless commander. Framing Custer as noble gave meaning to a devastating defeat. It was easier to honor him than admit he made fatal mistakes. The harsher reality tarnished the clean story of sacrifice.

10. Buffalo Bill as the Noble Cowboy

Buffalo Bill Cody is remembered as the heroic cowboy who embodied the Wild West. His traveling Wild West shows sold the image of daring scouts and noble frontiersmen. But Cody’s legend glossed over the reality that his fame came from killing bison to near-extinction and exploiting Native performers in staged battles. His persona was as much show business as history.

The myth of Buffalo Bill lasted because it gave Americans a romanticized frontier story. It allowed the nation to see expansion as adventure rather than destruction. His carefully crafted image was easier to cheer for than the truth of exploitation. The real story didn’t make for good theater.

11. Amelia Earhart’s Disappearance as a Glamorous Mystery

Amelia Earhart is often remembered as vanishing in a blaze of glory, leaving behind one of history’s great mysteries. Some theories even suggest daring escapes or secret government missions. In reality, the likeliest explanation is heartbreakingly ordinary: she ran out of fuel and crashed into the ocean. The myth persists because it feels more fitting for a trailblazing icon.

The glamorous disappearance kept her larger-than-life reputation intact. People wanted her to go out in mystery, not in tragedy. A mundane ending didn’t match her groundbreaking career. So speculation replaced acceptance of the probable truth.

12. John F. Kennedy as a Peacemaker President

JFK is often remembered as a champion of peace, especially after the Cuban Missile Crisis. His calm handling is credited with avoiding nuclear war. But Kennedy also ramped up U.S. involvement in Vietnam and supported covert operations to overthrow foreign governments. His presidency was marked by both diplomacy and aggression.

The myth of Kennedy as a pure peacemaker lasted because Americans needed a heroic narrative after his assassination. It was easier to freeze him in that moment of calm leadership than to examine the contradictions of his policies. The messy truth didn’t fit the Camelot story. So the myth became the enduring image.

13. Martin Luther King Jr. as Universally Loved

Today, King is celebrated as a national hero, with streets and holidays bearing his name. But during his lifetime, he was deeply unpopular with much of the American public. Polls in the late 1960s showed that most Americans disapproved of him, especially after he criticized the Vietnam War and economic inequality. He was harassed by the FBI until his assassination.

The myth of universal love made it easier for America to embrace his legacy without confronting how reviled he once was. It softened the reality that King challenged power structures most people supported. The ugliness of his treatment didn’t fit the sanitized memory. So his radicalism was smoothed into a safe, heroic myth.

14. Sacagawea as the Cheerful Guide

Sacagawea is often remembered as the smiling young woman who happily led Lewis and Clark through the wilderness. Schoolbooks describe her as eager to help, guiding the explorers with perfect knowledge of the land. In truth, she was a teenager who had been kidnapped, sold into slavery, and forced into a marriage with a much older man. Her role on the expedition was significant, but far more complicated and tragic than the cheerful image suggests.

The myth survived because Americans wanted a Native woman who fit the mold of a friendly helper rather than a victim of violence. By softening her story, Sacagawea became a symbol of cooperation rather than conquest. The reality of her captivity and limited power clashed with the heroic narrative. So the cleaner version stayed in classrooms for generations.

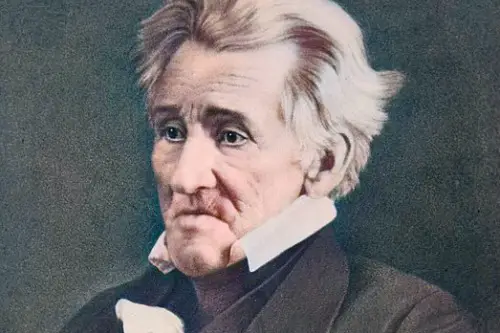

15. Andrew Jackson as the Champion of the Common Man

Andrew Jackson is often described as the rough-hewn president who stood up for ordinary Americans. His image as a fearless war hero and defender of democracy is still celebrated by some. But his policies included the Indian Removal Act, which led to the Trail of Tears and the death and displacement of thousands. His populism was built on the suffering of Native peoples and the entrenchment of slavery.

The myth endured because it was easier to glorify Jackson as a plainspoken man of the people. His brutality was rebranded as toughness, and his aggression as patriotism. The uglier truth of ethnic cleansing and exploitation was pushed aside. To keep his legend alive, the narrative focused only on his battles and bluster.

16. Clara Barton as the Perfect “Angel of the Battlefield”

Clara Barton is remembered as a saintly figure who selflessly cared for wounded soldiers during the Civil War. She’s often portrayed as tireless, gentle, and universally beloved. But the real Barton was also stubborn, controversial, and accused of poor management and favoritism in her relief work. Her career included clashes with male colleagues and constant struggles to keep authority.

The myth of the angel persisted because Americans wanted a simple symbol of compassion in wartime. Highlighting her flaws and conflicts would have complicated that comforting image. By smoothing over the rough edges, Barton became a maternal figure in national memory. The truth—that her impact was real but messy—got buried under the halo.

17. Rosa Parks as a Tired Seamstress

The familiar story says Rosa Parks was just a weary seamstress who refused to give up her seat one day. That version suggests her defiance was spontaneous, the act of an ordinary woman pushed too far. In reality, Parks was a seasoned activist who had trained for years in civil rights strategy. Her refusal was deliberate, planned, and part of a much larger movement.

The myth of a tired woman was easier for white America to digest. It stripped away the threatening idea of organized resistance and reduced her to a quiet individual moment. By oversimplifying her activism, the story became more palatable for schools and monuments. The truth of her radicalism and strategy didn’t fit the gentle image.

18. Nathan Hale’s Famous Last Words

Nathan Hale is remembered for his stirring final line: “I only regret that I have but one life to lose for my country.” The words are engraved in monuments and quoted in textbooks. But there’s no evidence Hale ever said them. The line was likely borrowed from a popular play of the time and attributed to him later.

The myth survived because Americans craved a clean martyr story from the Revolutionary War. A young patriot speaking perfect last words made for powerful propaganda. The real Hale may have died quickly and anonymously, but that didn’t inspire. So the scripted version became history.

19. The Wright Brothers as Overnight Geniuses

The Wright brothers are remembered as inventors who shocked the world by suddenly flying the first airplane. The story suggests two gifted men leapt ahead of everyone else with brilliance alone. In reality, they relied on years of trial and error, borrowing ideas from other pioneers whose names are now forgotten. Their “first flight” was one step in a messy, global race toward aviation.

The myth of sudden genius survived because America wanted a neat origin story for flight. It was more satisfying to crown two heroes than acknowledge a scattered web of innovators. By trimming away the failures and competitors, the Wrights became lone icons of invention. The truth—that progress was collective and uncertain—didn’t soar as well.

20. Harriet Tubman as a Magical Conductor

Harriet Tubman is often described as if she had almost supernatural powers guiding people to freedom. The stories make it seem like she single-handedly freed countless enslaved people through sheer bravery and cunning. While Tubman was undeniably courageous, the Underground Railroad was a network of many activists, and her work relied on countless helpers. Tubman herself also lived in poverty and faced constant danger long after the Civil War.

The myth of a magical lone rescuer erased the collective struggle of Black communities. It turned Tubman into a safe, saint-like figure rather than a radical leader who fought tirelessly. The harsher truths—her poverty, her battles with illness, and the danger she lived with—were forgotten. What remained was a simplified legend.

21. Theodore Roosevelt as the Hero of San Juan Hill

Textbooks often describe Roosevelt charging up San Juan Hill with his Rough Riders, leading the way to victory in the Spanish-American War. This version paints him as a bold soldier who personally turned the tide. In reality, Black soldiers of the Buffalo Soldiers regiments did much of the fighting and suffered the heaviest losses. Roosevelt’s role, while real, was later exaggerated in his political storytelling.

The myth lasted because Roosevelt himself promoted it, and the press happily echoed his version. A white politician charging heroically fit the nation’s appetite better than recognizing Black troops. The uncomfortable truth about who actually won the fight faded into the background. Roosevelt’s carefully crafted myth outlived the reality.

This post 21 Myths About American Heroes That Survived Because the Truth Was Too Ugly was first published on American Charm.