1. The Statue of Liberty (New York)

The Statue of Liberty has long been a symbol of welcome to immigrants, but its early years tell a different story. When the statue was unveiled in 1886, immigration was actually becoming more restricted, especially against non-European groups. The U.S. had passed the Chinese Exclusion Act just four years earlier, which barred most Chinese immigrants from entering the country. The “Mother of Exiles” arrived during an age when “Give me your tired, your poor” wasn’t exactly official policy.

Even the statue’s fundraising campaign faced indifference from Americans. It wasn’t until Joseph Pulitzer launched a newspaper drive to collect small donations that the pedestal was even finished. The statue’s meaning has evolved, becoming a rallying symbol for inclusion over time. But its birth moment was a lot more awkward than the plaques or postcards suggest.

2. Mount Rushmore (South Dakota)

Mount Rushmore is one of America’s most recognizable landmarks, but its origin story is complicated. The monument sits on land sacred to the Lakota Sioux, which was taken from them after the U.S. government violated the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868. To make matters worse, the sculptor Gutzon Borglum had earlier ties to the Ku Klux Klan while working on Stone Mountain in Georgia. That history makes the monument’s faces of American presidents feel a little less straightforward as symbols of freedom.

The project also disrupted Native communities and desecrated sites they considered spiritually important. The irony is that one of the presidents carved there—Theodore Roosevelt—had publicly supported assimilationist policies toward Indigenous people. The Lakota have never stopped protesting the monument’s existence and continue to call for the land’s return. It’s a national icon, but it’s built on a broken promise.

3. Lincoln Memorial (Washington, D.C.)

The Lincoln Memorial celebrates unity and freedom, but it opened in 1922 at the height of segregation. The dedication ceremony itself was segregated, with Black attendees forced to sit apart from white guests. Even the keynote speaker, Dr. Robert Moton, a prominent Black educator, wasn’t allowed to speak freely—his more pointed remarks on racial injustice were censored. The irony of honoring the Great Emancipator under those conditions is hard to ignore.

Still, the monument’s meaning changed over time. By the 1960s, the Lincoln Memorial became a powerful symbol of the civil rights movement, most famously when Martin Luther King Jr. gave his “I Have a Dream” speech there. Its marble walls have echoed both hollow hypocrisy and genuine progress. That evolution may be its most honest story.

4. Jefferson Memorial (Washington, D.C.)

Thomas Jefferson’s memorial praises his role as the author of the Declaration of Independence, but there’s no mention of his role as an enslaver. Jefferson owned more than 600 enslaved people over his lifetime and freed very few of them. He also fathered several children with Sally Hemings, one of the women he enslaved. The memorial’s polished quotes about liberty skip those contradictions entirely.

The design itself—modeled after the Roman Pantheon—reflects the founders’ self-image as philosopher-statesmen. But critics have long pointed out the hypocrisy of enshrining Jefferson without acknowledging the people whose labor made his life possible. The omission feels especially glaring in a city once built by enslaved workers. It’s a monument that celebrates freedom while quietly avoiding who was denied it.

5. Stone Mountain (Georgia)

Stone Mountain looms over Georgia with a massive carving of three Confederate leaders: Jefferson Davis, Robert E. Lee, and Stonewall Jackson. It’s the largest Confederate monument in existence—and was started by a sculptor who’d later design Mount Rushmore. The project began in the 1910s but was revived in the 1960s as an act of defiance against the civil rights movement. Its official dedication in 1970 was attended by Georgia’s segregationist governor.

The site also has a darker legacy as the symbolic birthplace of the Ku Klux Klan’s 20th-century revival. In 1915, the Klan held a cross-burning ceremony on the mountain to mark their return. For many visitors today, that knowledge makes the otherwise scenic spot feel uneasy. It’s a monument that can’t separate its stone from its story.

6. Liberty Bell (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania)

The Liberty Bell is famous for its crack and its inscription about liberty, but its early life wasn’t so pure. In the 18th century, the bell rang for gatherings that included slave auctions and public punishments. It didn’t gain its abolitionist symbolism until the 1830s, when anti-slavery groups adopted it as their emblem. That new meaning gave it a moral second act—but one the original founders never intended.

Even its iconic crack isn’t exactly a symbol of freedom—it’s just a mechanical failure. The bell cracked during testing and again during an 1840s attempt to repair it. Still, its imperfection became part of its legend, reflecting a fractured but hopeful ideal of liberty. Sometimes, the most patriotic symbols are patched together after the fact.

7. Mount Vernon (Virginia)

George Washington’s Mount Vernon estate is a pastoral shrine to America’s first president—but one that often downplays slavery. Washington enslaved more than 300 people on the property, though he freed them only upon his death. The visitor experience for decades centered on his leadership and hospitality, not the people forced to maintain it. Only in recent years has the estate expanded exhibits about the enslaved community’s lives.

Washington’s will to free his slaves after death is often cited as an act of moral courage. But it also meant that people he claimed to value remained in bondage during his lifetime. The contrast between the estate’s elegance and the realities of enslaved labor gives Mount Vernon a more complicated resonance. Behind the genteel image lies a plantation.

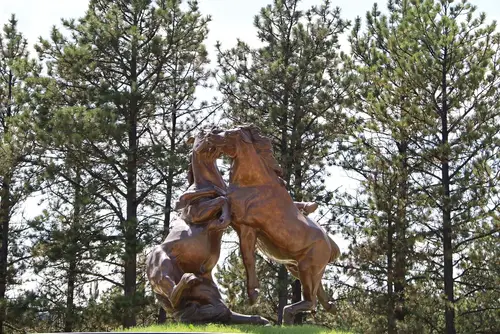

8. Crazy Horse Memorial (South Dakota)

The Crazy Horse Memorial was intended as a tribute to Native pride, but not all Indigenous people support it. Lakota leader Henry Standing Bear commissioned it in 1948, yet the massive project has stretched on for decades under a private foundation. Critics argue that carving into the Black Hills—a sacred area—is itself a violation of Lakota beliefs. Some even call it a second desecration following Mount Rushmore.

The sculptor, Korczak Ziolkowski, began the work without input from many Lakota elders and refused government funding to preserve his independence. Supporters see the memorial as a long-overdue Indigenous counterpoint to Rushmore. Detractors see it as a commercialized project that distorts the very values Crazy Horse stood for. Its unfinished state may be the most honest symbol of all—a story still unsettled.

9. Plymouth Rock (Massachusetts)

Plymouth Rock is supposed to mark where the Pilgrims first landed in 1620—but that’s mostly myth. No written record from the time even mentions a rock. The story didn’t appear until more than a century later, when a town elder pointed it out as the landing site. By then, it had become more patriotic folklore than verified history.

Even the rock itself has been moved several times and broken in half during its relocations. The version on display today has been heavily reconstructed and sits under a neoclassical canopy. For many Indigenous people, it symbolizes the beginning of colonization rather than freedom. It’s America’s most famous souvenir of a story we more or less made up.

10. The Alamo (Texas)

“The Alamo” stands as a shrine to Texas independence—but the conflict it memorializes had as much to do with slavery as freedom. Many Anglo settlers in Texas were fighting Mexico’s government, which had outlawed slavery. When they cried for “liberty,” part of what they meant was the liberty to keep enslaved people. That nuance rarely makes it onto the tour scripts.

The famous last stand in 1836 became mythologized through 19th-century nationalism and 20th-century Hollywood. Heroes like Davy Crockett and Jim Bowie were elevated to near sainthood, their flaws glossed over. In reality, the Alamo’s defenders fought to preserve a social order Mexico was dismantling. The monument remains a rallying point—but for whose freedom is still an open question.

11. Vietnam Veterans Memorial (Washington, D.C.)

When Maya Lin’s minimalist black wall design was chosen in 1981, it sparked outrage. Critics called it “a black gash of shame” and complained it lacked traditional heroism. Some even objected to Lin herself, a young Asian American woman, as the designer of a war memorial. Those early reactions revealed more about America’s discomfort with the Vietnam War than about the memorial itself.

Over time, though, the wall became one of the nation’s most moving monuments. Its reflective surface invites personal grief and reckoning rather than triumph. Veterans who once resisted it came to embrace its honesty. The controversy that nearly buried it now feels like part of its truth.

12. Arlington House (Arlington, Virginia)

Overlooking the nation’s most famous military cemetery stands Arlington House—the former plantation of Confederate General Robert E. Lee. It’s easy to miss that the estate was originally built with enslaved labor and later confiscated by the Union during the Civil War. The property became a burial ground partly to ensure Lee could never reclaim it. That decision gave the cemetery a subtle layer of vengeance alongside its reverence.

For decades, tours of Arlington House focused on Lee’s conflicted loyalties and noble character. Only recently have exhibits expanded to tell the stories of the enslaved families who lived there. It’s a reminder that even America’s most hallowed ground grew from contradiction. The silence of its plaques speaks volumes.

This post 12 Monuments with Stories Too Awkward for the Plaque was first published on American Charm.