1. Detroit, Michigan

Detroit grew rich on the skill of mass auto assembly, especially the kind perfected on early 20th-century factory lines. For decades, knowing how to work a stamping press or manage just-in-time parts by hand was a ticket to the middle class. Automation, robotics, and globalized supply chains hollowed out that specific skill set. The city still builds cars, but the hands-on assembly jobs it was built around no longer define its economy.

The reason Detroit belongs here isn’t decline alone, but how tightly the city’s identity was bound to one way of working. Entire neighborhoods rose around plants that needed thousands of line workers doing narrowly defined tasks. When those tasks disappeared or changed, the city had little cushion. Detroit’s story is about how a single dominant skill can become a liability when technology moves on.

2. Youngstown, Ohio

Youngstown was built on the skill of making steel the old-fashioned way, with blast furnaces, rolling mills, and armies of specialized laborers. Knowing how to run a furnace or finish steel by hand was once a lifelong profession. Mini-mills, foreign competition, and automation wiped out the need for that scale of labor. The city lost its economic anchor almost overnight in the late 1970s.

What makes Youngstown a clear example is how concentrated its economy was. Steel wasn’t just an industry there; it was the reason the city existed. When the mills closed, the skills they required vanished with them. Youngstown still exists, but the expertise it was designed to support is largely obsolete.

3. Gary, Indiana

Gary was literally founded by U.S. Steel to serve one purpose: making steel on an industrial scale. The city’s layout, housing, and infrastructure all revolved around mill work. Skills like open-hearth steelmaking and large-crew mill operations dominated local employment. Modern steel production needs far fewer workers with very different technical backgrounds.

Gary’s inclusion is about intentional design. This wasn’t a city that happened to get a steel mill; it was a steel mill with a city attached. When the demand for those specific industrial skills collapsed, the city had nowhere to pivot quickly. The mismatch between what Gary was built for and what the economy needed became painfully obvious.

4. Akron, Ohio

Akron earned the nickname “Rubber Capital of the World” because of tire manufacturing. The city depended on workers skilled in mixing compounds, curing rubber, and running massive tire plants. Global outsourcing and new materials sharply reduced the need for those jobs. The tire companies either left or transformed into research-focused firms with far fewer workers.

Akron’s story is a reminder that even advanced manufacturing skills can age out. Knowing how to make tires at scale was once cutting-edge industrial knowledge. When production moved elsewhere, those skills stopped being locally valuable. The city has since diversified, but its original reason for booming is gone.

5. Flint, Michigan

Flint was built around the skill of assembling vehicles and components for General Motors. Generations of residents learned specific manufacturing tasks tied directly to GM plants. As plants closed or automated, those narrowly focused skills lost value. The collapse hit Flint harder because alternatives were scarce.

Flint belongs on this list because of how dependent it was on one employer and one skill set. When GM no longer needed as many human assemblers, the city’s economic base eroded. Retraining takes time, money, and opportunity that Flint didn’t have in abundance. The result was a long-term struggle tied directly to obsolete work.

6. Rochester, New York

Rochester thrived on the skill of chemical film production and optical manufacturing, largely driven by Kodak. Making film required specialized chemical, mechanical, and quality-control expertise. Digital photography made those skills almost irrelevant within a single generation. Kodak’s collapse took the city’s economic identity with it.

What makes Rochester notable is how fast the change happened. Film wasn’t a fading craft over centuries; it vanished in decades. Workers trained for incredibly specific processes suddenly found their knowledge unwanted. Rochester’s challenge was adapting after the core skill it was built around disappeared.

7. Bethlehem, Pennsylvania

Bethlehem grew around steelmaking, particularly structural steel used in bridges and skyscrapers. Skilled laborers knew how to produce large steel beams at scale. Changes in construction methods and steel production made Bethlehem Steel uncompetitive. The plant closed in the 1990s, ending the city’s primary economic purpose.

Bethlehem’s inclusion is about specialization. The city wasn’t just making steel; it made a very specific kind of steel. When that niche collapsed, so did the employment base. Today, the former mill is a cultural site, a physical reminder of obsolete industrial skills.

8. Lowell, Massachusetts

Lowell was an early model of the American industrial city, built around textile mills. The key skill was operating and maintaining mechanized looms powered by water and later electricity. Textile production moved south and overseas where labor was cheaper. The expertise that once fueled Lowell’s growth no longer paid the bills.

Lowell matters because it shows how early industrial success can become a long-term weakness. The city trained generations for mill work that eventually left entirely. Unlike crafts that evolve, textile milling largely vanished from the region. The city had to reinvent itself after losing its founding skill.

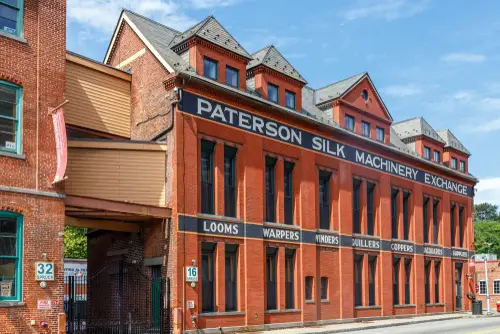

9. Paterson, New Jersey

Paterson was famous for silk production, earning the name “Silk City.” Workers specialized in weaving, dyeing, and finishing silk fabrics. Synthetic fibers and overseas production undercut the industry. The highly specific silk skills became economically irrelevant.

Paterson belongs here because silk wasn’t just an industry; it shaped the city’s culture and class structure. When silk declined, there was no equivalent trade to replace it. The skills were too specialized to transfer easily. That made the transition especially painful for the city.

10. Scranton, Pennsylvania

Scranton was built on anthracite coal mining and the railroads that served it. Mining hard coal required specialized physical skills and local geological knowledge. As coal demand dropped and mechanization increased, those jobs disappeared. Environmental and economic shifts sealed the industry’s fate.

Scranton’s case shows how energy transitions strand cities. The skill of extracting anthracite was once vital to the nation. When cleaner and cheaper energy sources took over, that expertise lost value. Scranton was left with infrastructure built for a vanished economy.

11. New Bedford, Massachusetts

New Bedford rose to prominence through whaling, which required skilled sailors, navigators, and ship outfitters. Whale oil once powered lamps and industry across the world. Petroleum replaced whale oil, collapsing the industry. The maritime skills that built the city became obsolete almost entirely.

New Bedford earns its spot because whaling vanished for technological and ethical reasons. There was no modern version of the trade to pivot into. The city had to abandon the very skill set that made it wealthy. Its historic district now tells the story of a lost profession.

12. Butte, Montana

Butte was built around hard-rock copper mining, earning the nickname “The Richest Hill on Earth.” Mining there required specialized underground skills and dangerous manual labor. Cheaper open-pit mining elsewhere and declining demand reduced the need for those workers. The city’s economy collapsed as mining scaled down.

Butte stands out because of how central mining skills were to daily life. The city existed to extract a specific resource in a specific way. When that method stopped being profitable, the skills lost relevance. Butte’s identity remains tied to work that no longer defines its future.

13. Rockford, Illinois

Rockford was once known as the “Screw Capital of the World,” specializing in fasteners and machine tools. Precision machining skills supported thousands of manufacturing jobs. Global competition and automation reduced demand for that labor. The factories closed or shrank dramatically.

Rockford belongs here because its expertise was both highly skilled and easily displaced. Once machines and overseas plants could do the same work cheaper, the local skill base eroded. The city’s economy was built around making things no longer made there. That gap has been difficult to close.

This post 13 Cities Built Around Skills That No Longer Matter was first published on American Charm.