1. Columbus Discovered America

You’ve probably heard the story: Christopher Columbus sailed the ocean blue in 1492 and “discovered” America. The problem is, that’s only part of the story—and not even the most important part, CNN explains. Indigenous peoples had been living in the Americas for tens of thousands of years before Columbus stumbled upon the Caribbean. Civilizations like the Maya, Inca, and Aztec were thriving long before Europeans even thought about crossing the Atlantic. Columbus didn’t “discover” anything; he just encountered land that was already home to millions.

Even more troubling, Columbus’s arrival initiated centuries of colonization, violence, and enslavement. This part of the narrative often gets glossed over in classrooms, where Columbus is hailed as a brave explorer rather than someone whose expeditions caused widespread suffering. If your teacher skipped this part, it’s worth revisiting history to learn what actually happened when Columbus showed up.

2. The Pilgrims and Native Americans Were Best Friends

We all grew up with that heartwarming Thanksgiving story: Pilgrims and Native Americans coming together to share a meal in the spirit of unity and gratitude. But the truth is far more complicated, as you can read in Smithsonian Magazine. While there may have been moments of cooperation, like the 1621 feast that inspired the Thanksgiving myth, relationships between settlers and Indigenous people were fraught with tension, mistrust, and violence. Colonists often stole Native land, disrupted their way of life, and brought diseases that decimated their populations.

That cozy Thanksgiving image can obscure the fact that colonization was largely disastrous for Indigenous peoples. The Wampanoag tribe, for instance, helped the Pilgrims survive their first harsh winter, only to face displacement and exploitation as more settlers arrived. This isn’t to say there wasn’t any goodwill between the groups, but the sanitized version we’re taught leaves out the full reality of the colonists’ actions.

3. The American Revolution Was All About Freedom

The Revolutionary War is often presented as a righteous fight for liberty against the oppressive British Empire. But the reality is that freedom wasn’t the same for everyone. For many white colonists, the revolution was as much about protecting their own economic interests—like avoiding taxes imposed by Britain—as it was about lofty ideals, the University of Pennsylvania explains. And let’s not forget that many of these same colonists enslaved African Americans, denying them any form of freedom or autonomy.

In fact, some enslaved people fought on the side of the British because they were promised freedom in return. While the Declaration of Independence spoke of “unalienable rights” and equality, these promises didn’t apply to everyone. The story we’re often told about the revolution oversimplifies the motivations and ignores the contradictions of a fight for liberty that left many people unfree.

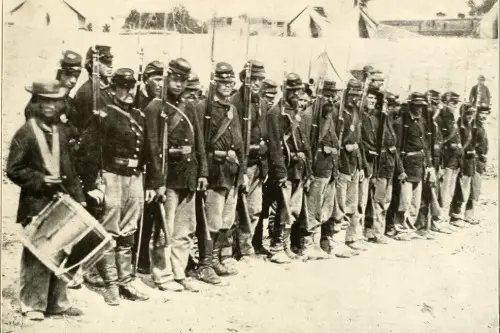

4. The Civil War Wasn’t Really About Slavery

Raise your hand if you were ever told that the Civil War was fought over “states’ rights.” While that’s technically not false, it’s only part of the picture—and a misleading one at that. The so-called “states’ rights” Southern leaders were fighting to preserve were explicitly about maintaining the institution of slavery, the National Park Service explains. Confederate leaders said as much in their speeches and documents, like the infamous “Cornerstone Speech” by Alexander Stephens.

Slavery wasn’t just a side issue; it was the cornerstone (pun intended) of the Southern economy and way of life. By framing the Civil War as a generic dispute over states’ rights, many classrooms downplay the central role of slavery in the conflict. Understanding this is crucial for grasping the true stakes of the war and its lasting impact on American society.

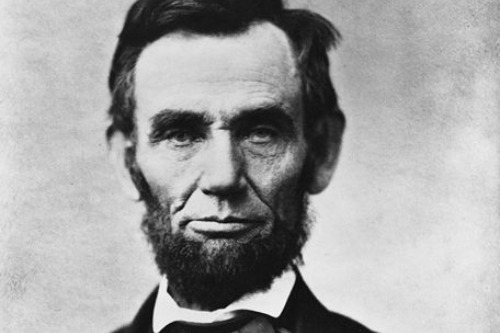

5. Abraham Lincoln Freed All the Enslaved People

We’ve all heard it: Abraham Lincoln was the Great Emancipator who freed all enslaved people in the United States. While Lincoln played a key role in ending slavery, the reality is more nuanced. The Emancipation Proclamation, issued in 1863, only freed enslaved people in Confederate states—not in the border states that remained loyal to the Union. Even then, it didn’t immediately free anyone; it was more of a symbolic act meant to weaken the Confederacy, the National Archives explain.

What’s more, Lincoln himself admitted that his primary goal was preserving the Union, not necessarily ending slavery. He was a complex figure whose views on race and equality evolved over time but didn’t fully align with modern ideas of racial justice. So while Lincoln deserves credit, the story of emancipation is more complex than what you might have learned in history class.

6. The U.S. Won Every War

A lot of history classes give the impression that the United States has never lost a war. But that’s not true! Take the Vietnam War, for example. The U.S. intervened in Vietnam to stop the spread of communism but ultimately withdrew in 1975 after years of heavy losses and public opposition. The war ended with the fall of Saigon, and North Vietnam achieved its goal of reunifying the country under communist rule.

The idea of American invincibility in war doesn’t just distort history; it also oversimplifies the complexities of international conflicts. By failing to acknowledge losses like Vietnam—or the stalemates in places like Korea—students miss the chance to learn valuable lessons about war, diplomacy, and the limits of military power.

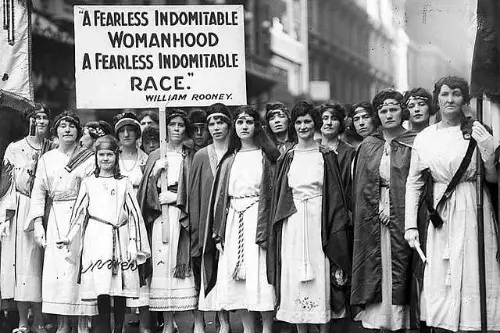

7. Women Didn’t Do Much Until They Got the Right to Vote

When it comes to women’s roles in history, the narrative often skips straight from the suffragette movement to modern feminism, leaving out centuries of contributions in between. Women were deeply involved in movements like abolition, labor rights, and temperance long before they gained the right to vote. Figures like Harriet Tubman, Sojourner Truth, and Clara Barton made enormous contributions to society that had nothing to do with voting.

Even during times when women were excluded from political life, they found ways to shape the nation’s history. Women’s contributions to the economy during World War II, for instance, are often reduced to Rosie the Riveter images when in reality, they were a crucial part of the war effort. Oversimplifying women’s history does a disservice to the complexity and depth of their impact on America.

8. The United States Has Always Been a Land of Opportunity

The “American Dream” is a powerful idea, but it doesn’t reflect the reality for everyone. While the U.S. has offered opportunities to many, systemic barriers have made it far less accessible for others. Enslaved people, Indigenous groups, and immigrants from non-European countries faced immense discrimination and limited mobility. Even policies like the Homestead Act, which provided land to settlers, were designed to benefit white Americans at the expense of Native peoples.

Immigration laws like the Chinese Exclusion Act or quotas favoring European immigrants also reveal that opportunity in America was historically restricted. By portraying the U.S. as a universally welcoming land of opportunity, history lessons can overlook the real struggles many groups faced—and continue to face—when trying to achieve the so-called American Dream.

9. The U.S. Was Neutral During World War II Until Pearl Harbor

The story goes that the U.S. was completely neutral until the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941. But in reality, the U.S. was already heavily involved in aiding the Allies through programs like Lend-Lease, which provided weapons and supplies to countries like Britain and the Soviet Union. President Franklin D. Roosevelt even referred to the U.S. as the “Arsenal of Democracy” long before the attack.

While Pearl Harbor was the tipping point that led to full-scale military involvement, it’s inaccurate to say the U.S. was sitting idly by beforehand. Understanding the steps leading up to the war—including economic sanctions on Japan and covert support for the Allies—provides a fuller picture of how the U.S. transitioned from neutrality to global power.

10. Slavery Was Just a Southern Problem

Many history lessons frame slavery as an exclusively Southern issue, but the truth is that the North was complicit, too. Northern states benefited economically from slavery through industries like textiles, which relied on cotton produced by enslaved labor. Banks and insurance companies in the North also profited by underwriting the slave trade and providing loans to plantation owners.

Even after Northern states abolished slavery, many continued to discriminate against Black Americans through segregation, unequal pay, and exclusion from certain jobs. The narrative of a morally superior North versus an oppressive South oversimplifies the widespread complicity in the institution of slavery and its aftermath.

11. Manifest Destiny Was a Noble Mission

Manifest Destiny is often taught as a noble idea—the belief that the U.S. was destined to expand from coast to coast, spreading democracy and civilization. But in practice, it led to the displacement and destruction of countless Indigenous communities, as well as the annexation of large swaths of land from Mexico. The Mexican-American War, which was justified by Manifest Destiny, resulted in the U.S. taking nearly half of Mexico’s territory.

The ideology of Manifest Destiny also served to justify racism and imperialism, portraying Native Americans and Mexicans as obstacles to progress rather than as people with their own rights and cultures. By romanticizing westward expansion, history classes often gloss over the violence and exploitation that accompanied it.

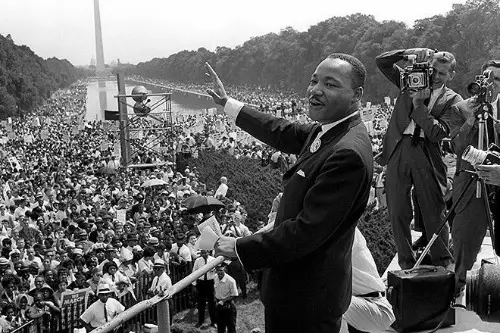

12. The Civil Rights Movement Ended Racism

Many students are taught that the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s ended racism in America. While the movement achieved monumental victories like the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act, it didn’t magically erase systemic racism. Issues like mass incarceration, police brutality, and racial wealth gaps persist today, showing that the struggle for racial equality is far from over.

Teaching the Civil Rights Movement as the definitive end of racism creates a false sense of closure and ignores the ongoing fight for justice. Figures like Martin Luther King Jr. and Rosa Parks are often presented as heroes who finished the job, rather than as part of a larger, continuing struggle. Understanding the movement’s successes and its limitations is key to grasping America’s ongoing challenges with race.