1. The First Thanksgiving Was a Peaceful Feast

We love the image of Pilgrims and Native Americans sitting down together in harmony over turkey and cranberry sauce. But that story is more fiction than fact. While there was a 1621 harvest meal between the Wampanoag and Pilgrims, it wasn’t called “Thanksgiving,” and it definitely wasn’t an annual tradition at the time. The idea of a peaceful, cross-cultural meal came much later, mostly as a way to create a unifying national myth.

In reality, tensions between settlers and Native Americans were already simmering, and violent conflicts would soon follow. The “First Thanksgiving” as we know it was largely shaped in the 19th century, especially by writers like Sarah Josepha Hale. She pushed for a national holiday and romanticized the Pilgrims to promote unity during the Civil War. So that cozy, peaceful image many of us grew up with? Total historical makeover.

2. Paul Revere Shouted “The British Are Coming!”

We’ve all heard the story: Paul Revere galloping through the night, yelling “The British are coming!” to alert the colonists. But historians agree he never actually said that—at least, not in those words. Most colonists still considered themselves British at the time, so that phrase wouldn’t have made sense. Revere was more likely to have warned that “the Regulars are out” or used similar terminology.

Plus, Revere wasn’t even the only rider—others like William Dawes and Samuel Prescott also made similar rides that night. The dramatic midnight ride story gained popularity thanks to Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s 1861 poem, which took quite a few creative liberties. Longfellow wasn’t writing history; he was stirring patriotism during a time of national division. And boy, did he succeed—just not in the accuracy department.

3. The Founding Fathers Loved Democracy

It’s easy to imagine that the Founding Fathers were all about democracy and wanted everyone to have a voice. But most of them were actually pretty wary of giving too much power to the general public. That’s why the Constitution originally left voting rights up to the states—and why only land-owning white men were generally allowed to vote. The founders were more into a republic than a true democracy.

People like Alexander Hamilton even spoke openly about distrusting the masses. The Electoral College system itself was created in part because the framers didn’t trust direct popular vote for president. It wasn’t until much later that the U.S. started resembling anything close to modern democratic ideals. So when people say, “We’re doing it like the Founding Fathers intended,” it’s worth asking—are we sure that’s a good thing?

4. Cowboys Were All White Guys With Hats and Guns

Thanks to old Westerns, many of us picture cowboys as lone, rugged white men riding off into the sunset. But the truth is, up to a quarter of cowboys were Black, and many were Mexican or Native American. The cattle-driving world was way more diverse than Hollywood ever showed. “Cowboy” itself comes from Spanish vaquero traditions, and the job was often dangerous, dirty work—not glamorous adventure.

After the Civil War, many formerly enslaved men became cowboys because the job didn’t require formal education. Yet pop culture erased them almost entirely from the narrative. The classic cowboy image was sanitized and racialized to appeal to 20th-century audiences. So if your mental image of the Wild West looks like a John Wayne movie, it might be time for a reboot.

5. The “War on Christmas” Has Always Been a Thing

Every December, we hear claims that there’s a modern “War on Christmas,” but ironically, early American Christians weren’t even into the holiday. In fact, Puritans in New England banned Christmas celebrations in the 1600s, viewing them as unbiblical and too rooted in paganism. For years, Christmas was just another workday in many parts of the U.S. It wasn’t even a federal holiday until 1870.

The idea that America has always centered Christmas—and that it’s now under threat—is more recent and media-driven. The modern outrage began picking up steam in the early 2000s, often fueled by cable news. But historically, the real “war” was against Christmas, not on behalf of it. So if you’re nostalgic for the “good old days” of Christmas in America, those days might not be what you think.

6. The Pledge of Allegiance Has Always Included “Under God”

Most Americans assume the phrase “under God” has always been part of the Pledge of Allegiance. But it was actually added in 1954, during the Cold War, as a way to distinguish the U.S. from “godless” communism. The original pledge, written in 1892, made no mention of religion at all. It was meant to promote national unity, not faith.

President Eisenhower supported the change after lobbying by religious groups like the Knights of Columbus. The phrase stirred controversy even back then, but it stuck—and now it’s taken as gospel (pun intended). Still, court challenges continue to this day, showing how recent and debated that addition really is. So no, the founding generation didn’t pledge allegiance “under God”—they didn’t even have a pledge.

7. The Boston Tea Party Was a Protest Against Taxes

The classic tale says colonists dumped tea into Boston Harbor because they hated taxes. But the Tea Act of 1773 actually lowered the tax on British tea—it just reinforced a monopoly by the East India Company. What really ticked people off was that it cut out local merchants, threatening colonial economic independence. So it wasn’t a blanket anti-tax protest; it was a targeted, strategic rebellion.

The Sons of Liberty used the tax angle to drum up broader support. They understood that “no taxation without representation” was a powerful rallying cry, even if the situation was more nuanced. The Boston Tea Party became legendary, but the motivations behind it weren’t as simple as we’re often told. So next time you hear it cited in a modern tax rant, maybe give that claim a second look.

8. Americans Have Always Loved Apple Pie

“American as apple pie” might be the most overused phrase in the cultural dictionary, but here’s the twist: apples aren’t even native to North America. Most apples in early America weren’t for pie—they were for cider. The sweet, edible varieties came later through cultivation, and the pie itself has roots in English and Dutch baking. It wasn’t until the 20th century that apple pie became a patriotic symbol.

The phrase took off during World War II, especially in advertising that linked everyday American life with national pride. Soldiers would say they were fighting for “mom and apple pie”—a PR goldmine. But it wasn’t based on a long, cherished tradition; it was marketing magic. So yes, apple pie is delicious—but it’s more ad campaign than ancient Americana.

9. George Washington Had Wooden Teeth

The image of George Washington stoically leading the nation with a mouthful of wooden dentures is burned into American folklore. But in reality, Washington never had wooden teeth. His dental prosthetics were made from a mix of materials—human teeth (sometimes from enslaved people), animal ivory, and metals like lead and gold. The wood myth likely came from the appearance of stained ivory, which looked grainy and dark over time.

Washington’s dental struggles were well documented; he began losing teeth in his twenties and was in near-constant discomfort. Still, the wooden teeth legend stuck because it made him seem more rustic and relatable—a humble farmer with simple tools. The truth is a lot more unsettling and complex, especially when you consider where some of those teeth came from. So the next time you picture the first president chewing on history with splinters, know it’s pure fiction.

10. Betsy Ross Sewed the First American Flag

Most schoolkids are taught that Betsy Ross sewed the first American flag at George Washington’s request. But there’s no solid historical evidence to back that up—her story only surfaced nearly a century later, thanks to her grandson’s testimony. Historians now believe the design of the flag was a collaborative process involving several people, and Ross may not have even been involved at all. There were many flag makers in Philadelphia at the time, and records don’t support the lone heroine narrative.

The Betsy Ross myth gained traction in the late 1800s, when the U.S. was looking for strong female figures to fold into patriotic storytelling. Her story fit perfectly into the era’s desire for simple, uplifting origin tales. But it was more about creating a national symbol than reporting facts. So while her name waves on in classrooms and history books, the real story is stitched together from guesswork.

11. Cowboys Settled the Wild West

The Wild West myth paints cowboys as brave pioneers taming an untamed frontier with grit and independence. But the land wasn’t exactly empty—Native American nations had lived there for centuries, and the U.S. government actively facilitated westward expansion through displacement and violence. The Homestead Act and railroad subsidies weren’t about rugged individualism; they were about systematic colonization. The cowboy-as-settler narrative conveniently ignores the government’s massive role in shaping the West.

Hollywood turned this skewed version into gospel, turning cowboys into lone heroes instead of underpaid ranch hands or ex-soldiers. In reality, most of the West was developed through federal incentives, corporate interests, and military force. Romanticizing cowboys as self-made men hides the real costs of expansion. So while the cowboy image is iconic, it’s rooted more in myth than hard truth.

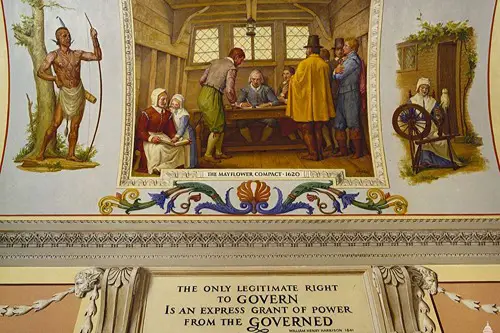

12. The Mayflower Compact Was the Birth of American Democracy

We often hear that the Mayflower Compact was the foundation of American democratic ideals. In reality, it was more about maintaining order among a group of settlers who didn’t all agree on how things should be run. It was a short, vague agreement that bound everyone to follow whatever laws the group later established. There were no real elections or guarantees of individual rights—just a promise of cooperation.

The Compact was later elevated as a proto-Constitution, especially in the 19th century, to show that democratic values had always been in America’s DNA. But the truth is more nuanced: it was a practical survival tool, not a bold political philosophy. It reflected more about necessity than ideology. The idea that it birthed democracy is a comforting—but misleading—revision.

13. The Declaration of Independence Was Signed on July 4th

Ask most Americans when the Declaration of Independence was signed, and they’ll say July 4, 1776. But that’s actually the date the final text was adopted—not the day it was signed. Most of the signatures weren’t added until August, and some trickled in even later. The big ceremonial signing happened over time, not all at once.

The July 4 narrative took hold because it was the date printed on early copies and became convenient for annual celebrations. It fit the mold of a clear, dramatic moment in history—even if it didn’t happen that way. Like many founding myths, this one serves more symbolic than factual purposes. So yes, we celebrate independence on July 4—but the signatures didn’t all show up for the party.

14. The Suburbs Were Built for the American Dream

The ideal of the suburban dream—white picket fences, two-car garages, and safe neighborhoods—seems like a natural outcome of postwar prosperity. But suburbs were deliberately engineered through policies like redlining, exclusionary zoning, and discriminatory lending. Government programs made it easier for white families to buy homes while denying those opportunities to people of color. The suburbs didn’t just grow—they were built to separate.

Levittowns and other planned communities often had contracts explicitly banning Black residents. These weren’t just personal prejudices—they were baked into federal housing policies. The nostalgic vision of the suburbs leaves out how rigged the game really was. So if you think the suburbs just “happened,” it’s time to reconsider who they were really built for.

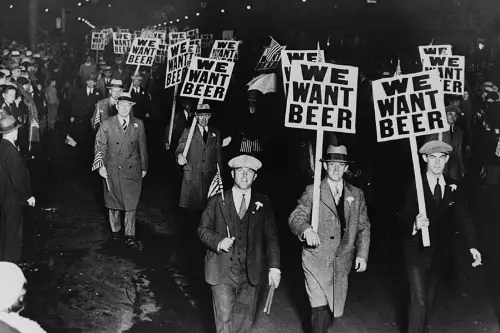

15. Prohibition Was Just About Alcohol

Prohibition is often remembered as a failed moral crusade to stop drinking, led by overzealous reformers and church groups. But the movement had strong political undercurrents—especially nativism, racism, and anti-immigrant sentiment. Many temperance advocates saw alcohol as a foreign problem brought by Irish, Italian, and German immigrants. Prohibition wasn’t just about health or morals—it was a way to control certain groups.

The 18th Amendment wasn’t a spontaneous moral panic—it was the result of decades of organized lobbying with deep cultural biases. Dry counties often overlapped with anti-immigrant sentiment, and enforcement was uneven at best. The image of Prohibition as a well-meaning, if misguided, policy is a sanitized version of a much more complex reality. Booze was just the surface issue.

16. The American Dream Was Always About Owning a Home

Today, owning a home is seen as the cornerstone of the American Dream. But that concept didn’t really take hold until after World War II, when returning soldiers were offered cheap mortgages through the G.I. Bill. Before that, most Americans rented, and the idea of owning a home was often out of reach. The postwar boom—and a lot of government support—reshaped the dream around real estate.

Massive suburban development, coupled with tax incentives, made homeownership seem both attainable and patriotic. Advertisers and politicians alike sold the idea that success meant a house, a yard, and a mortgage. But it wasn’t an age-old ideal—it was carefully manufactured. The American Dream has always been flexible; the version we know now is just the latest rewrite.

This post 16 American Traditions That Are Based Entirely on Fake Memories was first published on American Charm.