1. Pepto-Bismol

Pepto-Bismol was marketed as more than just an upset stomach remedy—it promised to protect the stomach from ulcers and serious digestive illnesses. Early advertising included diagrams of the stomach lining and pseudo-scientific explanations of its protective effects. In reality, while it can soothe symptoms, it doesn’t prevent most digestive diseases. Consumers were convinced by the visual science and clinical-sounding language.

The pink liquid became a symbol of health confidence in the family medicine cabinet. Doctors’ endorsements and “scientific illustrations” bolstered credibility. People purchased it believing it was a preventive medical solution. Today, it’s widely trusted for minor relief, but the original claims were greatly exaggerated.

2. Kellogg’s Corn Flakes

Kellogg’s Corn Flakes weren’t just breakfast food—they were marketed as a health miracle. In the early 1900s, Dr. John Harvey Kellogg claimed that Corn Flakes could reduce sexual urges, based on pseudo-scientific ideas about diet and morality. He suggested that bland foods would curb “unhealthy” impulses, despite having no real medical evidence. The cereal became a household name, largely thanks to these strange health claims.

Families bought into it because the marketing leaned heavily on science-sounding arguments. Doctors and magazines echoed the claims, giving it an air of legitimacy. People genuinely thought eating a bowl of flakes could influence their mental and physical health. Today, it’s mostly remembered as a quirky historical footnote in marketing history.

3. Lucky Tiger Hair Tonic

Lucky Tiger Hair Tonic promised more than just shiny hair—it claimed to stimulate growth and strengthen hair follicles. The bottles were plastered with testimonials and claims of “scientifically proven” formulas. In reality, there was no real science backing the tonic’s effects on hair growth. It relied on catchy labels and pseudo-science to make consumers feel confident in their purchase.

The marketing leaned on quasi-medical language to suggest that hair loss was a medical condition needing a tonic. Consumers trusted the product because it seemed endorsed by science. Barbers and local shops often sold it as a cure-all. It became a staple for those seeking a hair solution, even without genuine proof.

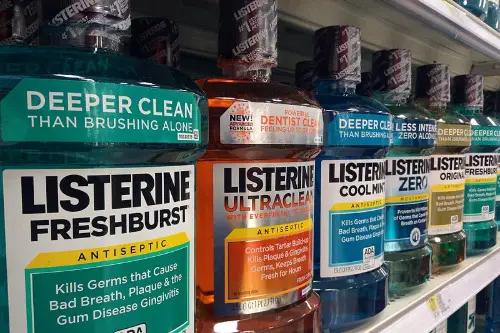

4. Listerine

Listerine is a classic example of fear-driven pseudo-science marketing. Originally created as a surgical antiseptic, it was marketed as a cure for halitosis, or “chronic bad breath,” which advertisers claimed could lead to serious diseases. The company pushed the idea that mouth bacteria could ruin social lives and even marriages. While it did kill germs in the mouth, the links to moral decay and disease were fabricated.

They used doctored statistics and invented studies to justify claims. Advertising emphasized the scientific aspect with charts and expert endorsements that were more fiction than fact. People bought it out of social fear rather than medical necessity. Today, Listerine is just a mouthwash, but its early marketing was full-blown pseudo-science.

5. Coca-Cola

Coca-Cola originally contained cocaine and was marketed as a medicinal tonic. Early ads suggested it could cure headaches, relieve exhaustion, and even treat morphine addiction. These claims leaned heavily on “scientific” sounding reasoning, but there was no rigorous evidence to back them. It was more about the allure of modern chemistry than actual medicine.

The beverage’s popularity soared thanks to its supposed health benefits. Advertisements featured doctors recommending it, giving the illusion of legitimacy. People consumed it thinking it was a health product rather than a sugary drink. It’s now mostly known for caffeine and sugar, not miracle cures.

6. Quaker Oats

Quaker Oats was marketed as a heart-healthy, energy-boosting food in the early 20th century. Ads claimed that the oatmeal could prevent nervous disorders and improve digestion, referencing scientific jargon that wasn’t backed by evidence. The company used pseudo-nutrition science to justify these claims. Consumers believed they were making a scientifically informed choice for their health.

The marketing played on fears of fatigue and illness common at the time. Doctors’ endorsements, whether real or fabricated, added credibility. People started associating oatmeal with longevity and vitality. In reality, it was just a wholesome breakfast cereal.

7. Vicks VapoRub

Vicks VapoRub promised to treat everything from colds to chest congestion in children. Ads claimed that the menthol-based ointment could “draw out germs” and cure respiratory illnesses. Scientists today agree it only provides temporary relief for symptoms, not the disease itself. The marketing exaggerated its effects with pseudo-scientific reasoning.

Parents bought it thinking they were providing medical treatment. Doctors were often quoted in ads, even though the evidence was weak. The product’s popularity relied on emotional appeals, framed with science-sounding claims. It’s now mostly seen as a comforting home remedy rather than a cure.

8. Bromo-Seltzer

Bromo-Seltzer was a headache remedy marketed as scientifically proven to relieve pain and nausea. It contained ingredients like sodium bromide, which was later recognized as potentially harmful. The advertisements suggested a precise, almost medical approach to treatment. People trusted it because it came with chemical-sounding formulas and diagrams.

Marketing often included “scientific” endorsements and case studies. Consumers were persuaded that the drink had modern medical backing. It became a common household remedy despite its risks. Eventually, concerns over safety forced reformulations.

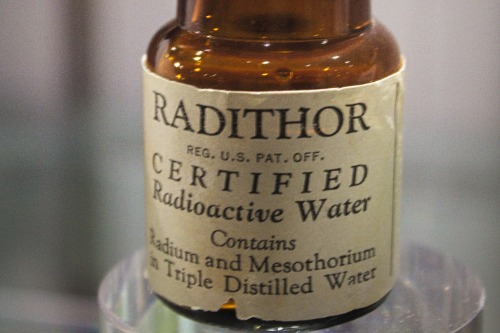

9. Radithor

Radithor was a radioactive tonic sold in the 1920s, promising to restore energy and vitality. The drink contained radium, and ads claimed it was “scientifically” proven to improve health. Unsurprisingly, it was extremely dangerous, causing severe radiation poisoning in some users. The pseudo-scientific marketing completely ignored real medical risks.

The public was fascinated by radiation as a cutting-edge science. Advertisements used technical jargon to give the illusion of safety and efficacy. People drank it for vitality and stamina. It’s now remembered as a cautionary tale of unchecked marketing and pseudo-science.

10. Sanka Coffee

Sanka Coffee was marketed as a healthy alternative to regular coffee in the early 20th century. Advertisers claimed that decaffeinated coffee could reduce heart strain and improve overall well-being. These claims were largely unverified and played on vague scientific reasoning. Consumers were led to believe there were health benefits beyond just avoiding caffeine.

The product capitalized on the growing awareness of diet and lifestyle. Scientists were sometimes referenced in ads to suggest authority. People embraced Sanka as a modern, health-conscious choice. Today, decaf is just a taste preference rather than a medical decision.

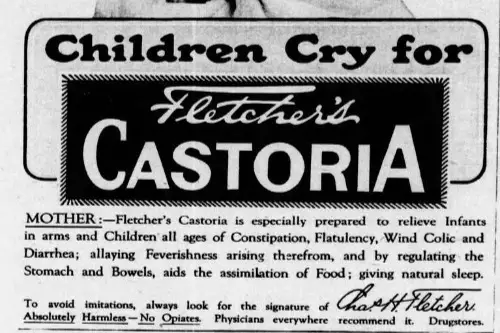

11. Fletcher’s Castoria

Fletcher’s Castoria was a children’s laxative marketed as “gentle, safe, and scientifically formulated.” Ads suggested it could prevent constipation and even improve a child’s disposition. There was no rigorous science proving these claims. The marketing emphasized safety and scientific credibility to reassure parents.

The product became popular because it was marketed as both natural and medically endorsed. Testimonials often included pseudo-medical reasoning. Parents felt like they were making a smart, scientific choice. Its longevity owes more to nostalgia than to actual science.

12. Grape-Nuts

Grape-Nuts cereal was marketed as a source of energy and vitality with scientific undertones. Early ads claimed that it could aid digestion and prevent diseases, using terminology that sounded clinical. There was no strong scientific evidence supporting these claims. Consumers were persuaded by the appeal of modern nutrition science.

Advertising often showed active, healthy people enjoying the cereal. The pseudo-scientific language suggested legitimacy. People bought it hoping to improve their health. Today, it’s just another breakfast option, though the marketing was influential.

13. Dr. Miles’ Nervine

Dr. Miles’ Nervine claimed to cure nervous disorders, insomnia, and anxiety. Ads described it as scientifically developed and clinically tested, despite lacking real studies. The formula contained ingredients like alcohol and sedatives, which could sedate but not cure underlying conditions. Consumers believed in its efficacy because of the science-like marketing.

The company used charts, testimonials, and “expert” endorsements to sell the product. People bought it as a modern, medical solution for stress. It was part of a wave of patent medicines with exaggerated claims. The pseudo-science created trust where none existed.

14. Pepsodent

Pepsodent toothpaste promised more than clean teeth—it claimed to remove the “film” on teeth that caused decay. Marketing suggested this invisible film was harmful and that their formula had special scientific properties to eliminate it. There was no real scientific basis for these claims. People were buying into the science talk more than the actual dental benefits.

Advertisers leaned on diagrams and technical-sounding explanations. Consumers felt reassured that they were doing something medically smart. This was a common tactic in the early toothpaste market. Today, Pepsodent survives, but its early hype was mostly pseudo-science.

This post 14 American Products That Were Marketed With Fake Science was first published on American Charm.