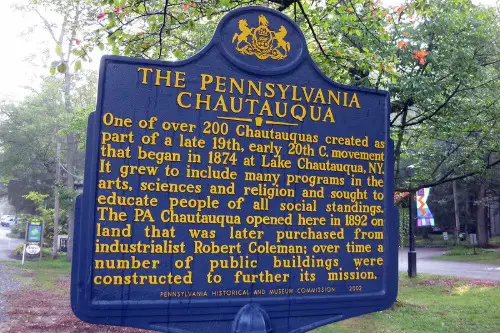

1. The Chautauqua Movement

You’ve probably never heard of it, but the Chautauqua Movement was like TED Talks before TED Talks existed. Starting in the 1870s, it brought speakers, music, and educational programs to rural communities across the U.S. At its peak in the early 20th century, Chautauqua events attracted millions of attendees, Kelsey Ables of The Washington Post explains. It was even called “the most American thing in America” by Teddy Roosevelt.

The movement helped spread ideas about social reform, temperance, and adult education. Traveling tents or local assemblies created real cultural hubs in small towns. It faded as radio and movies took over mass education and entertainment. But for decades, it was a powerhouse of grassroots learning and civic dialogue.

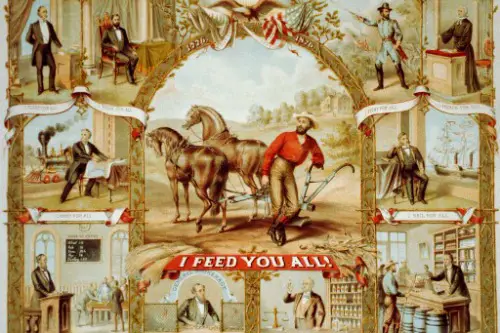

2. The Grange Movement

The Grange, officially known as the Patrons of Husbandry, started just after the Civil War in 1867, according to Robert Longley of ThoughtCo. It wasn’t just a farmers’ club—it was a major force advocating for railroad regulation, fair pricing, and rural community building. By the 1870s, it had over 800,000 members nationwide. The Grange pushed for cooperative stores and grain elevators to counteract corporate monopolies.

It wasn’t a political party, but it heavily influenced legislation, especially in states like Illinois and Iowa. The Grange helped spark early conversations around anti-monopoly laws. While its numbers declined, it laid groundwork for later populist and progressive reforms. It was a quiet but powerful engine behind agrarian activism.

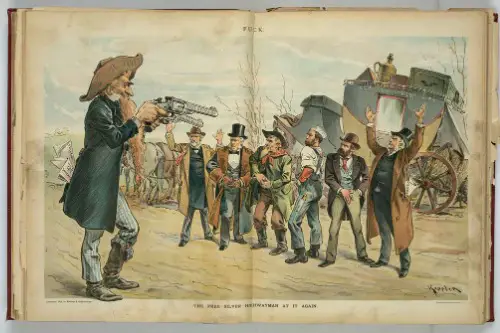

3. The Free Silver Movement

Money talk might sound dry, but in the 1890s, it stirred up massive political passion, according to Peter Y.W. Lee of Smithsonian Magazine. The Free Silver Movement wanted silver coins to be used alongside gold to back U.S. currency, believing it would help indebted farmers and workers. It peaked with William Jennings Bryan’s famous “Cross of Gold” speech in 1896. This was a defining issue of the presidential election that year.

It wasn’t just about coinage—it was about class, power, and who controlled the economy. Urban bankers opposed it fiercely, while rural America rallied behind it. Though it ultimately failed, it showed the deep economic divide shaping politics. Its legacy lived on in populist economic thought.

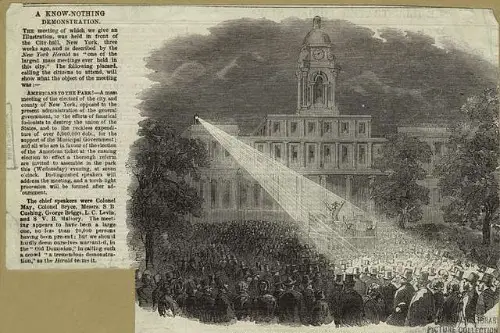

4. The Know Nothing Movement

The Know Nothings were the original anti-immigration political movement in America. In the 1850s, they surged into power with a message of nativism, anti-Catholic sentiment, and fears of foreign influence, Lorraine Boissoneault of Smithsonian Magazine explains. At one point, they held over 100 seats in Congress and elected several governors. The party’s real name was the American Party, but members were famously secretive—hence the nickname.

They reflected the anxieties of a country overwhelmed by immigration, particularly from Ireland and Germany. Though the movement collapsed by the late 1850s, it foreshadowed later waves of xenophobic politics. Their sudden rise showed how quickly fear-based messaging could go mainstream. It’s a reminder that U.S. nativism has deep historical roots.

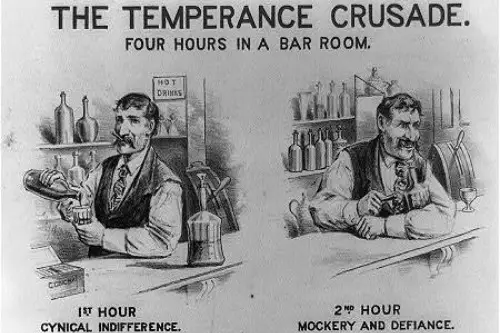

5. The Temperance Movement

Before Prohibition, the Temperance Movement had already been changing American society for decades. Led largely by women and religious groups, it wasn’t just about alcohol—it was about protecting families and social order. By the early 20th century, it had millions of members through organizations like the Women’s Christian Temperance Union. Their efforts directly led to the 18th Amendment.

Temperance leaders linked alcohol to poverty, crime, and domestic abuse, framing it as a moral crisis. They lobbied Congress, held marches, and produced endless educational material. While Prohibition eventually failed, the movement was remarkably effective at changing laws. It was one of the most successful moral reform campaigns in U.S. history.

6. The Greenback Party

Formed in the aftermath of the Civil War, the Greenback Party was all about monetary policy—specifically, keeping paper money in circulation. They opposed the return to the gold standard, which they saw as favoring banks over ordinary people. At its peak in the late 1870s, it drew significant support from farmers and laborers. They even ran presidential candidates and won seats in Congress.

What made them powerful was their critique of economic injustice in postwar America. The Greenbacks were early in connecting economic policy to social class. Though the party dissolved by the 1880s, many of its ideas were absorbed by the Populists. It was one of the first movements to frame inflation as a working-class issue.

7. The Back-to-the-Land Movement (1930s & 1960s)

People often associate “back-to-the-land” living with the 1960s hippies, but the idea had a strong resurgence during the Great Depression too. Families abandoned cities to live more self-sufficiently in rural areas, hoping to escape economic collapse. The movement revived again in the ’60s and ’70s with young people building communes and organic farms. It was a mix of political protest, environmentalism, and spiritual searching.

These weren’t fringe movements—they had magazines, bestselling books, and widespread appeal. Publications like The Mother Earth News helped connect people and share skills. The legacy still lives in today’s homesteading and off-grid trends. It was a quiet but influential rejection of consumer capitalism.

8. The American Indian Movement (AIM)

Founded in 1968, AIM started as a response to police brutality and systemic neglect of Native Americans. But it quickly grew into a major civil rights movement, staging high-profile protests like the occupation of Alcatraz and the Wounded Knee standoff. AIM fought for tribal sovereignty, treaty rights, and cultural preservation. At its height, it inspired Native youth across the country.

The federal government cracked down hard, and AIM splintered under pressure. But it reshaped public awareness of Native issues and forced change in policies and public perception. Its leaders were monitored by the FBI and targeted for disruption. AIM’s impact on Indigenous activism is still felt today.

9. The Populist Movement

This wasn’t just farmers griping—it was a full-blown political revolt in the 1890s. The Populist Party, or People’s Party, demanded banking reform, a graduated income tax, direct election of Senators, and government control of railroads. It gained traction in the South and Midwest, even winning several states. In 1892, their presidential candidate won over a million votes.

They gave voice to a broad coalition of working-class Americans disillusioned with elites. Many of their ideas were later adopted into national policy during the Progressive Era and New Deal. They pioneered a new style of mass political mobilization. And though the party faded, their legacy reshaped American politics.

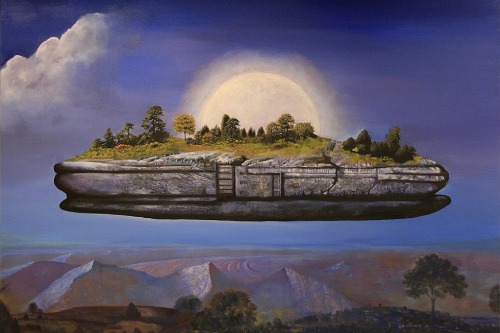

10. The Utopian Communities Movement

Before there were intentional living communities and co-ops, there were 19th-century utopian societies. Groups like the Shakers, Oneida, and Brook Farm tried to build perfect, egalitarian alternatives to capitalism. Some practiced communal ownership, others experimented with radical gender roles or spiritual ideals. At one point, there were dozens of these communities across the U.S.

They weren’t just spiritual outliers—they were critiques of the industrial age. These groups offered radical visions of how society could be organized differently. While most failed within a generation, their ideas sparked debates about work, family, and equality. They were the ideological ancestors of modern alternative-living movements.

11. The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW)

The IWW, or “Wobblies,” was a militant labor union founded in 1905 that aimed to organize all workers, regardless of skill or race. At a time when mainstream unions often excluded immigrants and Black workers, the IWW welcomed them. They led major strikes in textiles, timber, and mining, often clashing violently with police and private security. Their slogan was simple and radical: “One Big Union.”

Their influence peaked in the 1910s, with tens of thousands of members. The government crushed them during World War I, using arrests, deportations, and espionage. But their vision of worker solidarity and radical democracy remains influential. Today, they’re remembered as labor’s revolutionary wing.

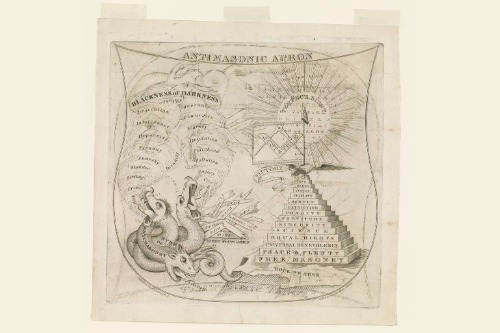

12. The Anti-Masonic Movement

In the early 1800s, fear of secret societies exploded into a full-on political crusade. The Anti-Masonic Party became America’s first third party, founded on suspicion of Freemasons after the disappearance of William Morgan in 1826. People feared the Freemasons wielded secret power over government and business. At its height, the movement won elections and even ran a presidential candidate.

Though it sounds wild today, the movement reflected deep anxieties about elitism and lack of transparency in government. It introduced political innovations like national conventions. While short-lived, it showed how conspiracy theories can shape political behavior. It’s a reminder that fear of hidden power has long roots in American life.

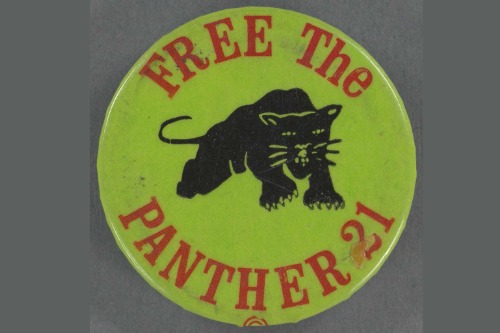

13. The Black Panther Free Breakfast Program

People know the Black Panthers for their militant image, but their community programs were equally powerful. The Free Breakfast for Children Program, started in 1969, fed thousands of kids every day in cities across the U.S. It inspired similar federal initiatives and helped shift national awareness toward food insecurity. Schools and community centers were often sites of radical care as well as protest.

This wasn’t charity—it was political action rooted in self-determination. The government viewed it as dangerous and monitored the programs heavily. But it changed how people understood the role of community in social justice. It’s one of the most successful and overlooked parts of 20th-century activism.