1. Keeping the Body at Home for Days

Before funeral homes existed, it was standard to keep the body in the home for several days before burial, according to Claire Cock-Starkey from Wellcome Collection. The parlor or kitchen table would often become the makeshift viewing area. Loved ones would sit with the deceased around the clock, both out of respect and to make sure they were actually dead. This period of home vigil was deeply emotional but also quite practical.

Ice blocks might be used to slow decomposition, and windows were opened for airflow. Sometimes mirrors were covered to prevent the spirit from getting trapped or to ward off bad luck. Children were expected to participate, often being told to kiss the forehead of the deceased as a farewell. The entire process was intimate, somber, and very different from today’s formal services.

2. Corpse Portraits Were a Thing

It was once common to pose the recently deceased for photographs, especially children, as a final keepsake. Known as post-mortem photography, the subjects were often dressed in their finest clothes and arranged to look alive, according to Bethan Bell from the BBC. Sometimes their eyes were painted open on the print, or family members would pose beside them as if nothing were amiss. It sounds eerie now, but it was often the only photo a family ever had of their loved one.

This practice peaked in the mid-1800s with the rise of the daguerreotype, which made photography more affordable. Traveling photographers even specialized in these types of images. While unsettling to modern eyes, they served as tangible proof of grief and remembrance. These photos are now collector’s items and historical curiosities.

3. Burying Loved Ones in the Backyard

Before formal cemeteries were commonplace, many Americans simply buried their deceased family members on their own property. It wasn’t considered odd—it was just practical, especially in rural areas where the nearest town was a day’s ride away, according to Rebecca Greenfield from The Atlantic. These “home burials” created family plots that could be visited easily, often marked with simple wooden crosses or stones. While sweet in its own way, it did raise hygiene concerns over time.

These backyard graves were sometimes right next to vegetable gardens or near the home’s well. As towns grew, ordinances began to outlaw this practice due to fears about water contamination. But even into the 19th century, many families continued doing it quietly. Today, a few remote homes still have these hidden graveyards, long forgotten.

4. Mourning Jewelry Made from Human Hair

Yes, people actually wore jewelry made from the hair of the deceased, according to Becky Little from National Geographic. It was a popular custom in the 18th and 19th centuries, especially among middle- and upper-class women. The hair would be woven into intricate designs and set into brooches, rings, or lockets. These keepsakes were considered both fashionable and deeply sentimental.

Hair, being durable, was seen as the perfect physical reminder of someone lost. Some families even commissioned elaborate braided hair wreaths to display in their homes. It was seen as a respectful way to carry a piece of your loved one with you. Today, these pieces are found in antique shops and museums—both macabre and fascinating.

5. Coffins with Escape Hatches

There was a widespread fear in the 18th and 19th centuries of being buried alive. So, inventors created “safety coffins” equipped with bells, air tubes, and even flags that could be triggered from inside. If the buried person awoke underground, they had a way to alert those above. It was morbidly ingenious, if not always reliable.

These fears were stoked by tales of premature burial, sometimes sensationalized in newspapers or literature. Some families even sat vigil over the grave for days, just in case. A few patents for these devices still exist, with diagrams that look straight out of a horror film. While likely never used successfully, the very idea reflects how terrifying death—and mistakes around it—could be.

6. Funeral Picnics in Graveyards

Believe it or not, cemeteries were once prime picnic spots. In the 1800s, Americans treated them like parks, bringing lunch to enjoy beside family graves. It wasn’t just about mourning—it was about spending time with the departed, celebrating their memory with food and fellowship. Children played, couples courted, and musicians sometimes performed nearby.

This was especially common in rural garden cemeteries, which were designed with walking paths and scenic views. People believed the dead would appreciate the company. While it seems morbid now, it was considered healthy to keep death close and social. The practice faded as cemeteries became more formal and segregated from everyday life.

7. Sin-Eating to Cleanse the Soul

In some early Appalachian communities, a ritual known as sin-eating was practiced to absolve the dead of lingering sins. A person—often poor or marginalized—was paid to eat bread and drink wine over the corpse, symbolically absorbing their sins. It was a blend of superstition and folklore rooted in European traditions. The sin-eater was both necessary and reviled, seen as spiritually “unclean.”

This practice existed on the fringes and never gained mainstream popularity. But it reflected deep anxiety about the afterlife and moral purity. It also shows how intertwined death and religion were in early America. While rare, it’s one of the more chilling customs in the nation’s funerary history.

8. Bells Tied to Corpses

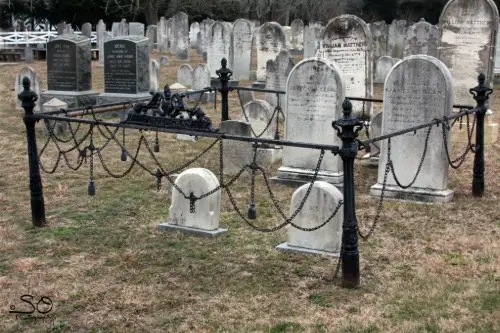

Aside from safety coffins, some people tied strings from the deceased’s hand to a bell above ground. The idea was that if they revived, they could ring the bell and be rescued. Graveyard keepers would listen at night, a job that sounds more like a ghost story than real life. The term “saved by the bell” may even stem from this fear-driven practice.

These bells were often mounted on wooden poles or grave markers. They weren’t just for show—families truly feared premature burial. Some graves were even designed with glass windows for body inspection. Thankfully, modern embalming and death confirmation standards eventually made this obsolete.

9. Wearing Black for Years

Mourning clothes weren’t just for the funeral—they were a long-term commitment. Widows were expected to wear black for at least a year, sometimes up to four. The idea was to signal ongoing grief and social withdrawal. Men had shorter mourning periods, often wearing black armbands instead.

There were even fashion guides detailing appropriate mourning attire by stage—deep mourning, half mourning, and so on. Children and servants were sometimes required to follow suit. The pressure to adhere to these rules was immense, especially in polite society. Over time, these customs faded, but echoes remain in our modern dress codes for funerals.

10. Coffin Furniture in the Parlor

Some households owned convertible furniture that could become a coffin. What looked like a sideboard or cabinet could be dismantled and reassembled into a burial box. It was a space-saving solution in frontier homes where resources were scarce. It also meant you were always prepared—morbid, yes, but practical.

These were typically homemade or purchased from traveling carpenters. Keeping one in the home wasn’t seen as eerie back then. Instead, it showed responsibility and foresight. Today, such furniture is rare but occasionally turns up in antique auctions or museums.

11. Funeral Invitations Were Delivered by Hand

Before newspapers and social media, families sent formal, often handwritten, invitations to funerals. These were sometimes black-edged cards with gothic script, hand-delivered to guests. It was a way to control who attended and ensure proper etiquette. Declining the invite without a good reason could be seen as a social slight.

In some regions, professional mourners were even hired to deliver these notices and attend the services. Invitations could include the dress code, time, and sometimes poetic verses. The tradition reflects how structured and ceremonial death was treated. It also reminds us how much slower and more intentional communication used to be.

12. Window Openings for Departing Souls

When someone died, it was common to open a window in the room immediately. The belief was that the soul needed a way to leave peacefully. If the window remained closed, the spirit might linger—or worse, become trapped. This custom had roots in European folklore but was common in colonial America.

Some families also covered mirrors, fearing the spirit might get caught inside. Others placed coins on the eyes or bells near the bed. These actions weren’t just symbolic—they reflected real fear and respect for the afterlife. Today, similar customs persist in various cultures around the world.

13. Children Were Encouraged to Touch the Dead

Unlike modern funeral practices that often shield kids from death, early Americans involved children directly. It was common for parents to ask children to touch or kiss the deceased, often on the forehead. This was meant to teach them acceptance and reduce fear of death. It was considered part of growing up.

Children also participated in wakes, vigils, and burials. They might help carry flowers, read scripture, or sing hymns. Though it seems harsh now, it reflected a time when death was more visible and less medicalized. Today, this openness has largely been replaced by sanitized, age-appropriate explanations.

14. The Corpse Was Sometimes Buried With the Clock

In some folk traditions, a broken or stopped clock was buried with the deceased. This symbolized the end of their time on earth and was believed to prevent the spirit from lingering. The practice was especially popular in isolated Appalachian or Southern communities. It was both poetic and deeply superstitious.

Clocks were often stopped at the time of death and never restarted. Some families kept them as mementos; others sent them to the grave. This blend of symbolism and practicality reflected how people coped with finality. Time, after all, was both a comfort and a cruel reminder.