1. Trash Can

Americans toss their garbage into a trash can. Elsewhere, people use a bin or a rubbish bin. To non-Americans, “trash can” sounds oddly dramatic—almost like a character in a Pixar movie. It also makes the simple act of throwing something away sound oddly important.

“Trash” itself isn’t as widely used globally; “rubbish” or “litter” often takes its place. And “can” for container is far more American than most realize, according to WordReference. In the UK, a “can” is something you drink soda from, not toss junk into. So when Americans talk about “taking out the trash,” it doesn’t always compute.

2. Faucet

To Americans, water comes out of a faucet. But to much of the world—especially in the UK and other Commonwealth countries—that’s a tap. Say “faucet” in London, and you’ll likely get a raised eyebrow or a polite “pardon?” It sounds oddly mechanical to ears used to “tap,” which feels more intuitive and direct.

The term “faucet” actually comes from Old French fausset, which referred to a bung in a barrel. Americans adopted it in the 19th century, while Brits stuck with “tap.” Even plumbers across the pond don’t use “faucet,” making it sound uniquely American, according to Laura Firszt from Networx. That’s probably why it stands out so much internationally.

3. Eggplant

In America, that deep purple vegetable is called an eggplant. But in most of the world—including the UK, Australia, and India—it’s known as an aubergine, according to Marissa Laliberte from Reader’s Digest. “Eggplant” sounds almost cartoonish or like something from Dr. Seuss to those unfamiliar with the term.

Interestingly, the word “eggplant” comes from a time when certain varieties were white and egg-shaped. Aubergine, on the other hand, comes from French, which borrowed it from Arabic and Sanskrit. It just feels a little more elegant—and a lot more global. No wonder “eggplant” raises eyebrows abroad.

4. Sidewalk

Americans walk on a sidewalk. But in the UK, Australia, and other English-speaking countries, it’s called a pavement, according to GitHub. The word “sidewalk” sounds oddly literal to those used to the more refined-sounding “pavement.” It also hints at the very American tendency to be ultra-specific in naming things.

“Sidewalk” emerged in the 18th century in America, likely as a way to distinguish walking areas from roads. In contrast, “pavement” has been around much longer, from Latin pavimentum, meaning a floor or surface. Ironically, in America, “pavement” often refers to the road itself. So in some ways, we’ve flipped meanings across the Atlantic.

5. Vacation

Americans take a vacation; Brits go on holiday. To ears outside the U.S., “vacation” sounds like a corporate buzzword rather than time off. It’s a word that feels more structured, almost like a scheduled work task.

“Holiday,” on the other hand, sounds more festive and laid-back. In the UK, it doesn’t necessarily mean a public day off—it’s just what they call travel breaks. “Vacation” comes from Latin vacare, meaning “to be free,” but it’s become very American in tone. It just doesn’t have the same carefree ring outside the States.

6. Realtor

If you’re buying a home in America, you’re likely dealing with a realtor. Outside the U.S., people generally say estate agent or property agent. “Realtor” sounds like a made-up title or the name of a robot to many non-Americans. It’s also a trademarked term in the U.S., which adds to the confusion.

The word was coined in 1916 by the National Association of Realtors. Its primary aim was to create a brand that distinguished their members. But the rest of the world never picked it up, sticking with more straightforward alternatives. The word’s legalistic sound makes it feel distinctly American.

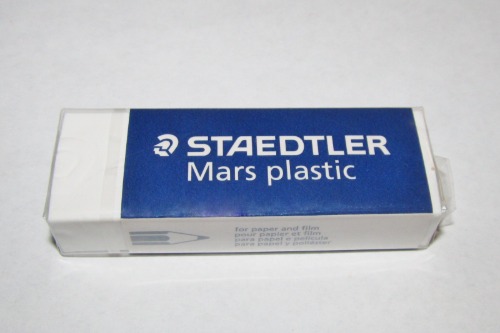

7. Eraser

In the U.S., you reach for an eraser when you make a pencil mistake. But in the UK and Australia, that same object is a rubber. You can imagine the awkwardness when a British child in an American classroom asks to borrow a rubber. That’s a blush-worthy moment that never fails to amuse.

The American term “eraser” focuses on the function of the object. “Rubber” describes what it’s made of—rubber, naturally. But in the U.S., “rubber” has a totally different slang meaning, which is why the British version can cause giggles. This one’s a classic cross-cultural language trip-up.

8. Zucchini

In America, it’s a zucchini. But across much of the English-speaking world, it’s a courgette. To outsiders, “zucchini” sounds almost exotic or Italian-flavored, even though the word is Italian in origin. Still, “courgette” comes from French, and that’s what stuck in the UK and beyond.

The difference reflects how various countries absorbed European culinary influences. The U.S. leaned Italian thanks to immigration waves in the 19th and 20th centuries. Meanwhile, Britain stuck with French due to historical ties. Either way, hearing “zucchini” outside America can feel unexpectedly foreign.

9. Dumpster

Americans toss things into a dumpster. In the UK, it’s a skip. “Dumpster” sounds industrial and almost brand-specific—probably because it is. It actually started as a brand name, much like Kleenex or Band-Aid.

The term comes from the Dempster Brothers Inc., who patented a “Dumpster” system in the 1930s. But the name stuck and became genericized in the U.S. Meanwhile, Brits adopted “skip” from a different angle, referring to large metal containers used for disposal. Say “dumpster” in London, and most people won’t know what you’re talking about.

10. Sweater

In the U.S., that cozy knit thing you wear when it’s chilly is a sweater. But in the UK, it’s more often a jumper. “Sweater” sounds oddly specific—as if it only refers to something you sweat in. Brits sometimes find it amusing, wondering if it’s workout gear or casual wear.

The word “jumper” likely comes from the French word jupe, which originally meant a tunic or short coat. Americans adopted “sweater” in the early 20th century, when it was associated with athletes sweating it out during exercise. Over time, it became a general term for warm knitwear. Still, the difference in terms makes transatlantic shopping a bit confusing.

11. Gasoline

In America, you fill up your car with gasoline—or just “gas.” In the UK and much of the world, it’s called petrol. To many non-Americans, calling a liquid “gas” feels bizarre and scientifically inaccurate. It sounds like you’re putting vapor into your car instead of fuel.

The word “gasoline” is believed to have been derived in the mid-19th century, possibly from the word gasolene, a brand name. Brits stuck with “petrol,” short for petroleum spirit. It’s a clearer descriptor in their view—and doesn’t sound like a chemistry mistake. This one can really cause confusion at the pump.

12. Diaper

American babies wear diapers. But across the UK, Australia, and many other countries, they wear nappies. To non-Americans, “diaper” sounds overly clinical or like something from a hospital catalog. “Nappy” feels softer and more in tune with baby talk.

“Diaper” comes from a type of cloth pattern and was used in English centuries ago before falling out of favor in the UK. Americans kept the term and repurposed it for babywear. Meanwhile, “nappy” emerged in Britain as a diminutive of “napkin,” referring to cloth used for the same purpose. So despite sounding like two different things, they actually share roots.

13. Cell Phone

In the U.S., everyone carries a cell phone. Elsewhere, it’s almost always called a mobile phone or just mobile. “Cell phone” sounds a bit sci-fi or prison-themed to many outside the U.S. The word “mobile” is seen as more natural since, well, it moves with you.

“Cell” refers to the cellular network structure developed in the U.S. telecom industry. The term caught on in North America but not abroad. In the UK and other countries, “mobile” better reflects the device’s function. When an American asks for a “cell,” it’s often met with a pause of confusion.

14. Band-Aid

In America, a small adhesive bandage is a Band-Aid. But that’s actually a brand name, not the generic term. Most other countries use “plaster” to refer to the same thing. Hearing “Band-Aid” abroad often sounds like you’re advertising Johnson & Johnson.

The generic term “plaster” has been around in British English since the 14th century. Americans gradually adopted “Band-Aid” after the brand became hugely popular in the 20th century. Much like Kleenex or Velcro, the brand overtook the common noun. Still, it sticks out when traveling abroad—no pun intended.

15. Drugstore

In the U.S., you pick up your prescription at the drugstore. But elsewhere, you’d head to the chemist or pharmacy. “Drugstore” can sound like a shady back alley operation to some non-Americans. The word “drug” itself carries heavier connotations outside the U.S.

In the UK, the word “chemist” reflects the profession of the pharmacist behind the counter. “Pharmacy” is common across Europe and parts of Asia, and feels more clinical. “Drugstore,” on the other hand, conjures up images of snacks, makeup, and greeting cards along with meds. It’s a very American retail hybrid.

16. Apartment

Americans live in apartments, but Brits tend to live in flats. The word “apartment” sounds a bit formal and upscale to those used to “flat.” It can even come across as slightly snobbish or overly architectural in tone. “Flat” is straightforward and sounds a bit more down-to-earth.

“Apartment” comes from the French appartement, which originally meant a separated set of rooms. The term caught on in American English but didn’t quite take root in the UK. Brits have been calling them “flats” since at least the 19th century. So when an American says they’re renting an apartment, it can sound a touch lofty.

17. Stroller

In the U.S., you push your baby in a stroller. Across the UK and many other countries, that’s a pushchair or pram. “Stroller” sounds like the baby is out taking a casual walk alone. Brits sometimes laugh at how passive the word makes the parent sound.

“Pram” is short for perambulator, a term that dates back to Victorian England. “Pushchair” is used more often for collapsible models. “Stroller” came into American English in the mid-20th century and emphasizes ease of use and mobility. But the word’s tone is distinctly American and doesn’t quite translate.

18. Soccer

America calls it soccer; the rest of the world calls it football. To non-Americans, “soccer” feels like a linguistic outlier—especially since the sport is actually played with feet. The irony isn’t lost on global fans when they hear Americans call American football just “football.”

The word “soccer” actually originated in England as a slang abbreviation for “association football.” But while Brits eventually dropped it in favor of “football,” Americans kept using “soccer” to distinguish it from their own version. It’s one of those words that quietly fuels international sports debates. And let’s be honest—it’s never just semantics when it comes to football.

19. Mailman

In the U.S., the person delivering your letters is the mailman—or maybe mail carrier. Elsewhere, it’s usually a postman or postal worker. “Mailman” sounds a bit like an old Western character to non-Americans. The word “post” just feels more official and universal.

“Mail” is rooted in American English and refers more broadly to the system of sending letters and packages. British English prefers “post,” a term with older Latin roots. “Mailman” also feels oddly gendered in a modern world aiming for neutrality. So the rest of the world stuck with “postman,” and it sounds more familiar to them.

20. Candy

To Americans, sweets are just candy. But to Brits and others, they’re sweets. “Candy” sounds like a child’s word in many parts of the world, almost like baby talk. “Sweets” feels more general and less commercialized.

“Candy” comes from the Arabic qandi, meaning made of sugar, and was adopted into American English via French and Italian. “Sweets” has been part of British vocabulary since the Middle Ages. While both mean sugar-packed treats, “candy” sounds more colorful and processed. It’s no surprise the rest of the world gives it the side-eye.

21. Overpass

Driving in the U.S., you’ll often cross or drive under an overpass. Elsewhere, you’d call that a flyover. To non-Americans, “overpass” sounds vaguely robotic or like a military maneuver. “Flyover” feels more poetic—and a bit more British.

“Overpass” is an American engineering term that entered common usage in the early 20th century. “Flyover” comes from the UK and references how the road literally flies over another. Americans use “flyover” too—but only to describe rural states passed over during cross-country flights. That little linguistic mix-up adds another wrinkle.

22. Period (as punctuation)

In the U.S., the dot at the end of a sentence is a period. In the UK, it’s a full stop. To Brits, “period” is more often associated with biology than grammar. So hearing someone say “end with a period” can cause a double take.

“Full stop” comes from the telegraph era, where messages needed clarity and finality. Americans simplified it to “period” in the 19th century. Both mean the same thing, but the American version can definitely sound confusing or even awkward abroad. Especially when explaining punctuation in mixed company.