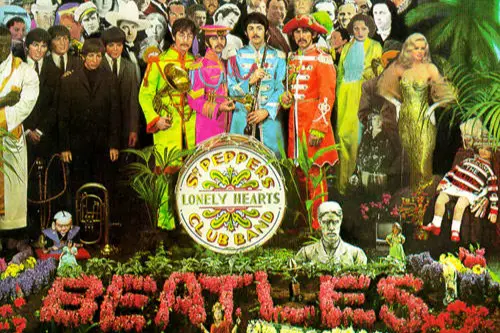

1. The Music Was a Psychedelic Dream

The Summer of Love wouldn’t have happened without its incredible soundtrack. In 1967, groundbreaking albums like Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band by The Beatles and Surrealistic Pillow by Jefferson Airplane shaped the sound of an era, Joe Taysom of Far Out Magazine explains. Free concerts in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park brought thousands together in a haze of swirling guitars and flower power. Music was the glue holding together this whirlwind cultural movement.

These weren’t just songs; they were anthems of a generation searching for meaning beyond suburbia. The Monterey Pop Festival, held that June, showcased artists like Janis Joplin, Jimi Hendrix, and The Who—legends in the making. It wasn’t just entertainment; it felt like spiritual communion. People genuinely believed the music could change the world.

2. Free Love Was (Mostly) Freeing

The counterculture championed the idea of “free love,” encouraging open relationships and rejecting the traditional confines of monogamy. For many, this was liberating—a way to explore intimacy and identity without shame or stigma, Daveen Rae Kurutz of The Beaver County Times explains. The birth control pill had become more widely available, making it easier for women to make their own choices. It was a revolutionary, if chaotic, push toward sexual equality.

In theory, love flowed freely and everyone was on the same page. In reality, it didn’t always work out so harmoniously. Some people got hurt, and emotional boundaries were often unclear or ignored. But for many, the freedom to love who and how they wanted was a powerful act of rebellion.

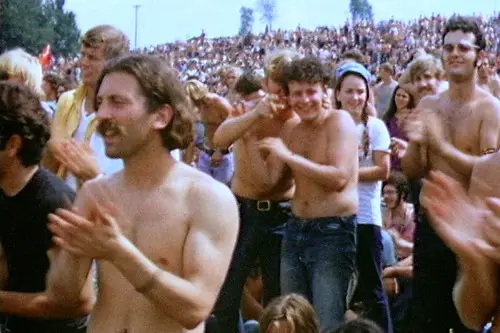

3. People Came Together for a Shared Cause

There was a real sense of unity that summer—hippies, activists, and dreamers all converged in San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury neighborhood. They weren’t just there to drop acid and listen to music; they were trying to build a better world. Anti-war sentiment, civil rights activism, and ecological awareness all mixed into a potent, hopeful blend, Michael J. Kramer of The New York Times explains. It was the belief that love could actually conquer all.

What made it special was that so many people believed in the dream. Communal living, shared resources, and peace marches felt like stepping stones toward a utopia. Even if it was naive, the sincerity was electric. For one hot summer, it really felt like change was possible.

4. Psychedelics Opened Minds

LSD wasn’t just a party drug—it was treated as a mind-expanding tool. Inspired by figures like Timothy Leary, many believed psychedelics could unlock higher consciousness, Sheila Weller of Vanity Fair explains. Trips were often taken with intention, whether through music, meditation, or nature walks. People described seeing the world in radiant color and feeling deeply connected to the universe.

It wasn’t all hallucinations and giggles—some claimed life-changing insights. The drug use was often tied to spiritual exploration, not just escapism. Psychedelics helped fuel the art, music, and philosophy that made the Summer of Love feel cosmic. For better or worse, it was a chemical catalyst for cultural transformation.

5. Art and Fashion Were Wildly Creative

Everything about the Summer of Love was loud, colorful, and full of flair. Tie-dye, bell bottoms, fringe, beads—what people wore was a statement of rebellion and joy. Posters by artists like Victor Moscoso and Wes Wilson turned concert promos into psychedelic masterpieces. Even the streets became canvases for vibrant expression.

Fashion wasn’t just about looking cool—it was about rejecting conformity. The more flamboyant and out-there, the better. Creativity flowed from the individual outward, and everything was an opportunity for self-expression. It made even a casual walk through the Haight feel like a living art exhibit.

6. Spirituality Took New Forms

Many young people began exploring alternative spiritual paths, including Eastern philosophies like Buddhism and Hinduism. Gurus like Maharishi Mahesh Yogi attracted Western followers with promises of inner peace and enlightenment. It was part of a larger rejection of organized religion and a turn toward personal experience. Meditation, yoga, and mysticism became tools for self-discovery.

This spiritual curiosity wasn’t just trend-chasing—it reflected a deep hunger for meaning. People wanted to feel connected to something bigger than themselves. The fusion of peace, love, and spiritual exploration helped define the era. Even if not everyone reached nirvana, the journey mattered.

7. It Was a Moment That Felt Like Magic

There was something ephemeral and golden about the Summer of Love—it felt like lightning in a bottle. The convergence of people, ideas, art, and idealism created a rare cultural alchemy. Even skeptics couldn’t deny the powerful sense of possibility in the air. It was a dream shared by hundreds of thousands.

For those who were there, the memories often carry a glowing, surreal quality. It was messy, imperfect, and short-lived—but it mattered. The Summer of Love became a symbol of what could be, if only for a season. And sometimes, that’s enough to spark revolutions.

1. The Haight Was Overcrowded and Filthy

What started as a bohemian paradise quickly turned into an overcrowded mess. An estimated 100,000 people descended on San Francisco that summer, overwhelming the city’s infrastructure. Streets filled with trash, public restrooms were rare, and hygiene was often an afterthought. The smell alone could ruin your flower crown.

Locals were not thrilled by the influx. Many hippies had little money or plans beyond “tune in, turn on, drop out.” That meant a lot of hungry, homeless youth wandering the streets. The utopia started to stink—literally.

2. Bad Trips and Drug Burnouts

Not every psychedelic journey was a pleasant one. LSD and other hallucinogens could trigger terrifying experiences, especially when taken in unsafe settings. Without guidance or moderation, many people suffered from paranoia, confusion, or long-term psychological effects. The idea of expanding your mind could quickly spiral into losing it.

Emergency rooms reported an uptick in drug-related incidents that summer. The media began calling it a public health concern. Timothy Leary’s call to “turn on, tune in, drop out” wasn’t exactly a roadmap for stability. For some, the promise of enlightenment turned into a very dark tunnel.

3. Exploitation Was Rampant

With so many idealistic young people arriving in the Haight, it didn’t take long for predators to follow. Drug dealers, pimps, and other opportunists saw easy targets in the naïve and trusting. Young runaways, especially girls, were vulnerable to abuse and manipulation. The dream of free love sometimes hid very real dangers.

Reports surfaced of sexual assault, coercion, and grooming behind the peace signs and daisies. Some communes operated like cults, with charismatic leaders preying on followers. It’s an ugly truth that often gets glossed over in nostalgic retellings. But exploitation was very real—and very present.

4. The “Love” Wasn’t Always Consensual

In an era pushing boundaries, consent sometimes got lost in the shuffle. The rhetoric of free love didn’t always translate into respect or communication. Some men used it as an excuse to pressure women into being intimate, dismissing discomfort as “hang-ups.” What sounded like liberation could easily turn into manipulation.

The lack of clear standards or protections made it easy for boundaries to be crossed. It’s not that everyone behaved badly—but the culture didn’t always call it out when they did. Sexual freedom without emotional intelligence led to a lot of pain. It’s a reminder that true liberation requires mutual respect.

5. Sanitation and Disease Were a Real Problem

When you’ve got thousands of people living communally with limited access to clean water or toilets, things get gross fast. Reports of hepatitis and lice outbreaks weren’t uncommon. Medical services were stretched thin, and many people simply didn’t believe in going to the doctor. You can imagine how that worked out.

The lack of infrastructure meant that many got sick or went untreated. Sharing food, drink, and personal items didn’t help. It clashed hard with the image of a pure, healthy counterculture. Hygiene just wasn’t a high priority.

6. The Movement Was Mostly White

Despite its radical goals, the Summer of Love wasn’t exactly a model of inclusion. The scene was overwhelmingly white and middle-class, even as people borrowed heavily from Black and Indigenous cultures. Civil rights activists often saw the hippies as naïve or disconnected from real political struggle. For many people of color, it felt like another movement that didn’t really include them.

The aesthetic borrowed from African, Indian, and Native American traditions, but the movement didn’t always show respect or understanding. That tension remains a big part of its legacy. It’s not that people were intentionally racist—it’s that they often didn’t notice who was missing. Representation wasn’t part of the conversation yet.

7. It Didn’t Last

By the time fall rolled around, the Summer of Love was already unraveling. The crowds thinned, the trash remained, and the Haight turned into a shadow of its former self. Crime increased, and hard drugs like heroin began replacing psychedelics. The dream, it seemed, had come crashing down.

A symbolic funeral—“The Death of the Hippie”—was held in October 1967 to mark the end of the movement. It was supposed to remind people that real change couldn’t be found in a trend or a scene. But it also felt like a surrender. The magic faded fast, and the cleanup lasted much longer than the high.