1. Coffin Furniture in the Parlor

In frontier days, space and materials were limited—so some families kept dual-purpose furniture that could convert into coffins. What looked like a sideboard or bench could be disassembled into a burial box. This meant you were always ready for death, an idea both practical and grim. It also saved time in emergencies.

Carpenters sometimes advertised these convertible items to remote families. It wasn’t considered strange; it was just part of being self-reliant. Today, such furniture might seem more like a Halloween prop than a household staple. Still, examples occasionally appear in antique collections or folklore museums.

2. Keeping the Body at Home for Days

Before funeral homes became the norm, it was customary to keep the deceased at home for several days. The body would often be laid out in the parlor or on the kitchen table, where friends and family gathered to mourn. Loved ones maintained a constant vigil, both to honor the dead and to ensure the person was truly gone. This home-based wake created a deeply personal, if intense, grieving process.

To manage decomposition, families used blocks of ice or opened windows for ventilation. Mirrors were often covered to prevent bad luck or to keep the spirit from getting trapped. Even children were expected to participate, sometimes being told to kiss the deceased’s forehead goodbye. The modern funeral parlor has made this tradition feel distant—and a bit unsettling.

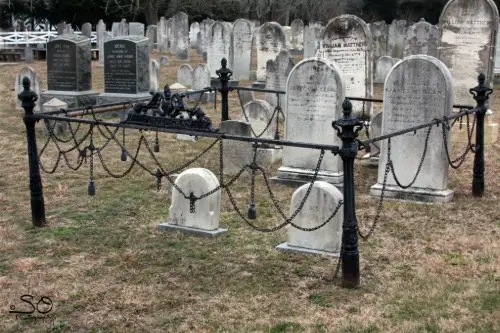

3. Burying Loved Ones in the Backyard

Before cemeteries were widespread, it was typical to bury family members on private land. These backyard plots, especially common in rural areas, were convenient and deeply personal. Wooden markers or simple stones would often denote the gravesite, and visits were a regular part of home life. The practice wasn’t seen as morbid—just practical and respectful.

Sometimes, these graves were located alarmingly close to wells or gardens. As cities expanded, public health concerns led to regulations banning private burials. Still, many families continued the tradition quietly for years. Today, remnants of old family cemeteries occasionally turn up in backyards or on construction sites.

4. Mourning Jewelry Made from Human Hair

Crafting mourning jewelry from the hair of the deceased was a popular 19th-century custom. Women would weave strands into intricate brooches, bracelets, and lockets as lasting tributes. Hair was chosen because it doesn’t decay, making it a symbol of permanence. These pieces were both deeply sentimental and surprisingly fashionable.

Entire wreaths made from braided hair were also displayed in parlors. For grieving families, this was a way to hold a physical part of the person close. While the thought of wearing someone’s hair today feels morbid, back then it was an act of love and memory. Antique shops and museums occasionally still display these unusual artifacts.

5. “Safety Coffins” to Prevent Premature Burial

Fear of being buried alive led to some truly bizarre innovations in the 18th and 19th centuries. Safety coffins were designed with bells, breathing tubes, and flags to allow someone mistakenly buried to signal for help. The idea may sound absurd today, but stories of premature burial were common and terrifying at the time. These coffins were a last-ditch effort to ensure peace of mind.

Some families even hired grave watchers to sit vigil for days after the funeral. Patents for these devices still exist, showing elaborate designs that seem more like horror props than real inventions. Although it’s unclear how often these contraptions worked, the paranoia was very real. Today, accurate death confirmation makes such measures unnecessary—and a little creepy in hindsight.

6. Funeral Picnics in Graveyards

In the 19th century, graveyards weren’t just for mourning—they were for gathering. Families would bring food, blankets, and even musical instruments for leisurely afternoons among the tombstones. It was a way to “visit” loved ones, honor their memory, and stay socially connected. Children played freely, and some cemeteries even hosted formal events.

These rural or garden cemeteries were often landscaped to resemble parks. People saw death as part of the life cycle, not something to be hidden away. The practice faded as cemeteries became more formal and separated from daily life. Still, it’s hard to imagine modern families spreading out a picnic next to headstones.

7. Sin-Eaters Took on the Sins of the Dead

In some early American communities, a person known as a sin-eater was paid to ritually consume food and drink over the body of the deceased. This act symbolically transferred the departed’s sins to the eater, “cleansing” the soul for the afterlife. The sin-eater was often a marginalized figure—necessary, but socially avoided afterward. It was a strange blend of folk religion and guilt management.

This tradition came from older European customs and never reached mainstream practice. Still, it lingered in isolated communities, especially in the Appalachian region. The act reflects how seriously people took the concept of spiritual purity after death. Today, the very idea sounds like something out of dark folklore.

8. Bells Tied to Corpses

Aside from high-tech safety coffins, some families took a simpler approach—tying a string from the corpse’s hand to a bell above the grave. If the person “woke up,” they could ring for help. Graveyard staff would listen for any bells, though it’s unclear if any were ever actually rung. The idea gives chilling weight to the phrase “saved by the bell.”

These makeshift systems were especially common during outbreaks when burial procedures were rushed. Some graves even had glass viewing panels to monitor the body. Eventually, medical advances made such fears obsolete. Still, the ingenuity of these grim devices is both fascinating and unsettling.

9. Wearing Black for Years

Wearing black after a death wasn’t just a tradition—it was a social requirement, especially for women. Widows could be expected to dress in mourning clothes for a year or more. This extended mourning served as a visual signal of grief and was strictly observed. Men typically had a shorter mourning period, sometimes marked by black armbands.

There were even rules for “half mourning,” where grays and purples replaced solid black. Fashion magazines offered guides on proper mourning attire. Children and even household staff were sometimes included in the dress code. Compared to today’s more casual funerals, it was an intense and prolonged display of loss.

10. Corpse Portraits Were a Thing

Known as post-mortem photography, this tradition involved taking formal portraits of the deceased. Families would dress their loved ones in their best clothing and sometimes pose them upright or arrange them to look lifelike. Eyes might be painted open in the photograph, or siblings posed beside the body to simulate normalcy. What now feels eerie was once a cherished final image.

These portraits were often the only photographs ever taken of the person, particularly for children. The rise of daguerreotypes in the 19th century made this practice more accessible. Traveling photographers even specialized in post-mortem images. Today, these pictures are haunting relics of an era when death was more visibly integrated into daily life.

11. Funeral Invitations Were Delivered by Hand

Before telephones or newspapers, funerals were announced through formal, hand-delivered invitations. These were often black-edged cards with ornate lettering and solemn verses. Accepting the invitation was a mark of respect, while declining could strain social ties. Some wealthy families even hired messengers to deliver them in mourning clothes.

These cards served as more than just announcements—they were ceremonial tokens of loss. In some cases, they included details about attire or religious rites. The process was intimate and personal, far removed from today’s digital RSVPs. It shows how much care once went into even the smallest part of a funeral.

12. Window Openings for Departing Souls

As soon as someone died, a window in the room was often opened to allow the soul to escape. This small ritual was believed to ensure a peaceful departure and prevent the spirit from becoming trapped. The practice had deep roots in European folklore and was widely adopted in colonial America. It reflected a spiritual understanding of death’s physical space.

Some families also covered mirrors or turned them to face the wall. They feared spirits could be caught inside reflective surfaces. Coins might be placed on the eyes to help the soul pay its way to the afterlife. These customs mixed reverence, fear, and practicality in fascinating ways.

13. Children Were Encouraged to Touch the Dead

Rather than shielding children from death, early Americans involved them in the grieving process. Kids were encouraged to touch or kiss the body as a way to say goodbye. This hands-on approach aimed to normalize death and reduce fear. It was considered a formative life experience.

Children attended wakes, carried flowers, or read verses at burials. Death wasn’t hidden—it was part of everyday life. Though the practice may seem harsh now, it fostered a familiarity that many modern families avoid. Today, funerals tend to be more age-restricted and emotionally distant for kids.

14. The Corpse Was Sometimes Buried With the Clock

In some folk traditions, stopped clocks were buried with the deceased to symbolize that their time had ended. Clocks were sometimes halted at the moment of death and never restarted. This poetic gesture was thought to prevent the spirit from lingering in the world. It also served as a tangible reminder of finality.

In more isolated communities, the practice took on spiritual overtones. Families believed the clock’s silence helped the soul move on. Others kept the clock as a relic, forever marking the time of loss. Either way, time itself became part of the grieving process.

15. Reusing Graves After Decomposition

In crowded or rural graveyards, it was once common to reuse burial plots after the body had fully decomposed. Family members might dig up a site to make room for another relative, simply pushing old bones aside. The remains were often reburied deeper or moved to a nearby ossuary. This was practical, if unsettling by today’s standards.

Grave reuse was sometimes done without headstones or clear records, leading to confusing and sometimes gruesome discoveries later. In some cases, skulls or femurs would be displayed as part of the cemetery’s heritage. The idea of disturbing a grave feels taboo now, but in the past, it was often just how things were done. Today, laws and customs have made this practice rare—and highly controversial.

This post 15 Ways Americans Honored the Dead That Would Feel Creepy Today was first published on American Charm.