1. Homer Simpson

Homer Simpson isn’t just a cartoon dad—he’s a caricature of the American everyman, according to Gurjit Kaur from NPR, and that’s exactly why he hits so hard. He’s lazy, impulsive, underqualified, and constantly messing up—but he’s also loyal, oddly lovable, and trying his best (usually). Since The Simpsons debuted in 1989, Homer has stood in for countless working-class Americans caught between economic frustration and personal confusion. His job at the nuclear power plant, complete with donuts and daydreams, became a symbol of blue-collar stagnation in a rapidly shifting society.

Homer’s failures are epic, but so is his relatability. He’s clueless about politics, reckless with money, and baffled by his kids—and somehow, that makes him feel more real than most live-action TV dads. While he’s a punchline, he also reflects real anxieties about work-life balance, identity, and the slow erosion of the American Dream. In his own absurd, ridiculous way, Homer became a national mirror—and America couldn’t look away.

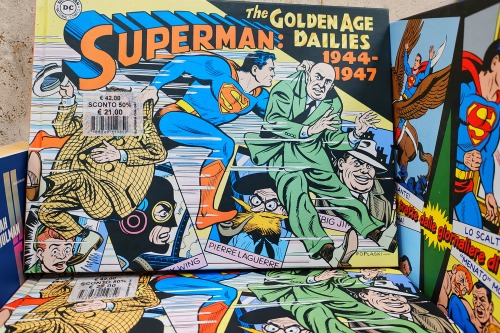

2. Superman

He might be from Krypton, but Superman is about as American as it gets, according to Roy Schwartz from the Literary Hub. Created during the Great Depression by two Jewish teenagers, he embodied the immigrant experience—an outsider who chose to fight for truth, justice, and the “American Way.” Over the decades, he’s remained a symbol of moral clarity in times when real leaders faltered. He didn’t just punch bad guys; he reminded America what it aspired to be.

His alter ego, Clark Kent, reflected a certain humility and decency that resonated with working-class America. As wars, scandals, and social upheaval came and went, Superman stayed unwavering. In fact, during World War II, he was used in propaganda to support war bonds and American unity. Few fictional characters have stood as firmly in the American conscience for so long.

3. Atticus Finch

In To Kill a Mockingbird, Atticus Finch stood tall in a town twisted by prejudice, proving that one man’s quiet courage could echo loudly, Casey Cep from The New Yorker explains. He defended a Black man falsely accused of a heinous crime in 1930s Alabama—not because he thought he could win, but because it was right. Atticus became a touchstone for what moral integrity looks like under pressure. Many readers came to see him not just as a lawyer, but as the embodiment of American justice.

The character was so iconic that Gregory Peck’s film portrayal in 1962 won him an Oscar—and earned Atticus a permanent seat in America’s cultural memory. He taught generations to see the law not just as rules but as a tool for equity. While real legal systems disappointed, Atticus remained a figure people believed in. His presence in high school curricula cemented his role in shaping how Americans think about fairness and race.

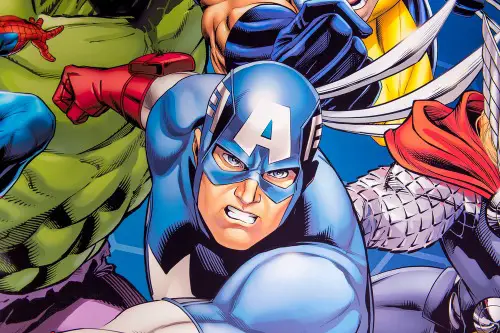

4. Captain America

He was literally created to punch Hitler in the face, and that’s exactly what he did on the cover of his first comic in 1941. Captain America, or Steve Rogers, started out as a scrawny kid from Brooklyn who got a chance to fight for his country—and for decency. He wasn’t just a soldier; he was the idealized version of what a soldier should be: brave, selfless, and unwilling to blindly follow orders. His moral compass never seemed to waver, even when America’s did.

From wartime propaganda to Cold War anxieties and modern political allegories, Cap has adapted while still standing for justice, Cait Caffrey from EBSCO Research Starters explains. In the Marvel Cinematic Universe, his refusal to compromise during Civil War was a direct commentary on surveillance and freedom. He questioned power, even when it came from within his own government. Captain America didn’t just represent the flag—he challenged us to live up to it.

5. Uncle Sam

He’s not from a novel or comic book, but Uncle Sam is still technically a fictional personification. Born out of political cartoons in the 19th century and popularized during World War I by the “I Want YOU” poster, he became the face of American patriotism. Unlike real politicians who fade from memory, Uncle Sam remained ever-present, often resurfacing during moments of national crisis or war. His finger pointed straight at Americans, demanding personal responsibility and unity.

Though he’s often used to represent government authority, he’s also a mirror of how America sees itself—stern, principled, and a little larger-than-life. Over time, artists and activists alike have subverted his image to critique policy, turning a symbol into a conversation. Whether he’s on recruitment posters or protest signs, Uncle Sam sparks reactions. Few fictional icons have had such long-standing influence on national identity.

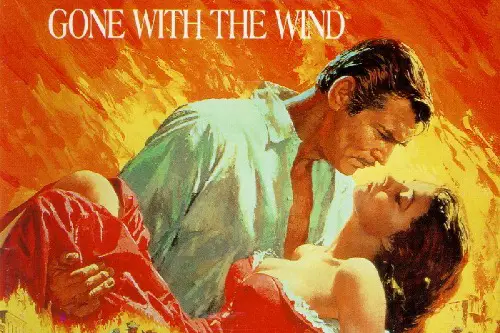

6. Scarlett O’Hara

Scarlett O’Hara from Gone with the Wind is one of the most complex figures in American fiction—equal parts heroine and antiheroine. As a Southern belle who survives the Civil War and Reconstruction through grit and cunning, she embodied a certain myth of American survivalism. Her story isn’t easy or clean, and neither is America’s. She lies, cheats, and manipulates—but she never gives up.

Published in 1936, Margaret Mitchell’s novel became a runaway success and the basis for one of the most iconic films of all time. Scarlett’s tenacity during a time of national upheaval made her a relatable figure for Depression-era readers. While the book has been rightly criticized for its romanticized view of the antebellum South, Scarlett’s personal evolution speaks to America’s obsession with reinvention. She’s as controversial as she is unforgettable—and that’s part of what makes her so influential.

7. Jay Gatsby

Gatsby might’ve thrown the wildest parties in West Egg, but what he really represented was the American Dream in its most tragic form. Obsessed with wealth, reinvention, and an unattainable love, Gatsby shows us how the dream can curdle into delusion. He came from nothing, changed his name, and built an empire just to impress someone who barely remembered him. That’s the dark side of American ambition, wrapped in a tuxedo.

F. Scott Fitzgerald didn’t just create a character—he captured a generation’s disillusionment. During the roaring ’20s and its aftermath, Gatsby became a symbol of how the pursuit of success can hollow a person out. His green light across the bay has become a literary shorthand for hope just out of reach. And that idea still resonates in a country built on dreams.

8. Archie Bunker

He was bigoted, loud, and stuck in the past—but Archie Bunker also helped America see itself more clearly. On All in the Family, his outdated views were put on display not to endorse them, but to challenge them. Norman Lear created Archie as a kind of mirror to the American living room—imperfect, prejudiced, and often ridiculous. Yet, despite his faults, viewers related to him, laughed with him, and sometimes even saw themselves in him.

Archie’s character forced conversations about race, gender, and class into prime-time TV at a time when most shows avoided them. He didn’t change overnight, but that was the point—neither did America. By making us cringe and chuckle at the same time, Archie humanized the very struggles tearing the country apart. He didn’t fix the culture wars, but he sure aired them out.

9. Tony Soprano

Tony Soprano wasn’t the first antihero on TV, but he was the one who changed the game. He was a mob boss, sure—but also a suburban dad with panic attacks, therapy sessions, and existential dread. In the late ’90s, when America was shifting from idealism to cynicism, Tony captured that complexity. He represented the duality of being powerful and broken, public and private, brutal and vulnerable.

The Sopranos helped usher in the Golden Age of television by showing that viewers were ready for morally complicated protagonists. Tony’s contradictions mirrored America’s own—violent but civilized, ambitious but anxious. He forced audiences to confront their own values by making them root for someone undeniably bad. That discomfort rewired what we expected from our stories—and ourselves.

10. Wonder Woman

When Wonder Woman burst onto the scene in 1941, she wasn’t just a female superhero—she was a feminist statement wrapped in a golden lasso. Created by psychologist William Moulton Marston, she was meant to embody the power of compassion over brute force. In a world dominated by male heroes, Wonder Woman offered a new kind of strength rooted in empathy. Her homeland, Themyscira, was a utopian vision of female leadership and cooperation.

Over the years, she’s been everything from a wartime nurse to a Justice League icon. Her image has been adopted by women’s rights movements and has been analyzed in academic circles for decades. When her solo film finally hit theaters in 2017, it broke box office records and shattered glass ceilings. Wonder Woman doesn’t just fight villains—she redefines what power can look like.

11. Holden Caulfield

Holden Caulfield from The Catcher in the Rye is the patron saint of American teenage angst. With his red hunting hat and deep disdain for “phonies,” Holden captured the voice of a postwar generation unsure of what to believe in. He wasn’t a role model—he was a mirror, reflecting the disillusionment lurking behind middle-class comfort. His alienation felt radical in a culture obsessed with conformity.

J.D. Salinger’s novel became a rite of passage for millions of readers, and Holden’s voice influenced decades of literature and pop culture. He introduced American readers to the idea that rebellion could be internal, emotional, and unheroic. His honest vulnerability became a new kind of strength. Even now, when someone says they’re “over it,” they owe a little something to Holden.

12. Bugs Bunny

Bugs Bunny might be a wisecracking cartoon rabbit, but he’s also a full-blown American icon. He emerged during World War II as a cheeky underdog who outsmarted bullies with brains and charm, not brute force. Bugs broke the fourth wall, challenged authority, and never took himself too seriously—qualities that Americans love to see in themselves. He was sarcastic, clever, and unflappable, even when the odds were against him.

During the 1940s and ’50s, Bugs became a cultural ambassador of sorts, appearing in war-themed cartoons and poking fun at America’s enemies. His voice and attitude—crafted by Mel Blanc and a team of brilliant animators—helped define the tone of American animation. Even his catchphrase, “What’s up, Doc?” became part of the national lexicon. In a way, Bugs Bunny helped America laugh through some of its darkest moments.

13. Paul Bunyan

Paul Bunyan, the giant lumberjack with his blue ox Babe, isn’t just a tall tale—he’s folklore distilled into Americana. He sprang from oral traditions and lumber camp stories in the late 1800s, but he became widely popular through promotional pamphlets in the 20th century. Paul symbolized expansion, hard work, and a can-do attitude—ideal for a growing nation that believed in Manifest Destiny. His outsized feats matched America’s own outsized ambitions.

Though entirely fictional, Paul was treated like a cultural hero. Statues of him stand in small towns across the country, often drawing tourists and reinforcing regional pride. His stories celebrated nature and industry, often without acknowledging the environmental cost—mirroring America’s own blind spots. Still, he represents a rough-and-tumble spirit that many associate with early American identity.

14. Don Draper

In Mad Men, Don Draper sold the American Dream even as he was falling apart inside. Set in the 1960s, the show tracked his journey from confident ad man to deeply broken person, and in doing so, dissected what American success really means. Draper was a genius at crafting images of happiness and fulfillment for clients, while failing to find either for himself. He was America’s polished exterior—and its haunted interior.

The brilliance of Don’s character is that he wasn’t just a product of his time; he was a commentary on it. His identity was literally invented, stolen from a dead soldier—a metaphor for postwar reinvention. While he helped define what masculinity and success looked like, he also showed how hollow those ideals could be. He made viewers question whether the Dream he was selling was ever real.

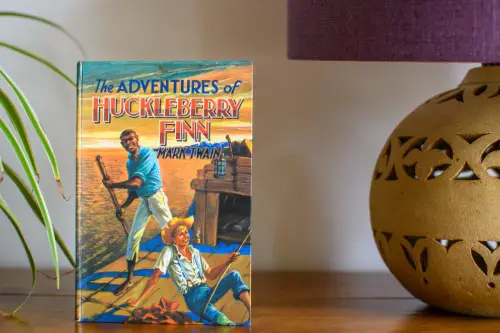

15. Huckleberry Finn

Mark Twain’s Huck Finn is more than just a mischievous kid on a raft—he’s America’s original rebel. In The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, he questions the values of the adult world around him, particularly the morality of slavery. At a time when America was grappling with its post-Civil War identity, Huck was a compass pointing toward conscience over conformity. His moral awakening represented the better angels of America’s nature.

Through Huck, Twain exposed the contradictions in American society. He made readers uncomfortable in all the right ways by showing how racism was deeply ingrained even in “decent” folks. Huck’s decision to “go to hell” rather than betray Jim was a radical act of empathy. That made him one of literature’s most enduring voices of American individualism and justice.