1. The 2012 Mayan Calendar Apocalypse

The 2012 Mayan Calendar apocalypse is another moment in recent history when a lot of people collectively feared the world was going to end, Charles Q. Choi from NBC News explains. Some interpreted the end of the 13th baktun on the Mayan Long Count calendar as a prediction of global catastrophe, sparking a widespread belief that the world would cease to exist on December 21, 2012. People made plans for survival, stockpiled emergency kits, and even sought shelter in remote locations, convinced that something catastrophic was on the horizon. However, when December 21 came and went, everything continued as usual.

The panic wasn’t just limited to fringe groups—it also got a significant amount of media attention, further fueling the fear. It turned out that the Mayan calendar was simply a marker of a new cycle, not a prediction of the apocalypse. This episode highlights how people’s collective fears can be amplified by misinformation, especially when an event like the end of a calendar seems significant but has no real basis in reality. In the end, the world didn’t end, and all those survival kits went unused.

2. The Great Toilet Paper Shortage of 2020

At the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, one of the most bizarre moments of mass panic was the toilet paper shortage, according to Steve Banker from Forbes. As news of the virus spread, people rushed to stores and cleared the shelves of toilet paper, even though there was no logical reason to do so. The fear that essential goods would run out led to a sort of hoarding frenzy, with families storing massive quantities of toilet paper they likely wouldn’t need for months, if not years. This led to empty aisles, wild panic buying, and even fights over the last remaining packs.

In reality, there was never a real shortage of toilet paper—the supply chain was intact, and factories continued to produce the product. What caused the shortage was purely a matter of panic buying and irrational behavior fueled by fear. The fact that this fear centered around something as mundane as toilet paper illustrates how quickly people can spiral into hysteria when uncertain times arrive. It remains a reminder that, even when the facts don’t support it, a mass panic can lead to irrational actions with long-lasting effects.

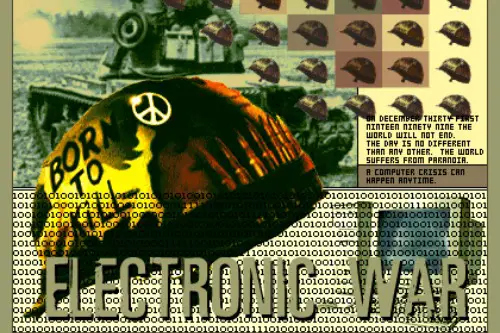

3. The Y2K Panic

The Y2K scare in the late 1990s was a massive moment of collective anxiety in the U.S. People feared that when the year turned from 1999 to 2000, computers would crash because they only used two digits to represent the year, according to Jack Mitchell from NPR. Businesses, governments, and individuals spent millions preparing for potential disruptions, stockpiling food, water, and even gasoline. As the clock struck midnight on January 1, 2000, absolutely nothing happened—no widespread tech failures, no chaos, just a very quiet transition into the new millennium.

While there were certainly some tech glitches here and there, the worst-case scenarios never materialized, and the panic felt overblown in hindsight. Experts attribute this to a massive amount of work by programmers and engineers who addressed the problem well before the year ended. In many ways, the Y2K panic was a perfect example of how fear can snowball into something much bigger than reality. It’s a reminder that when people collectively believe something catastrophic will happen, the mere act of preparing can end up defusing the crisis.

4. The “War of the Worlds” Radio Broadcast

In 1938, Orson Welles’ radio adaptation of War of the Worlds caused nationwide panic, even though it was a work of fiction, A. Brad Schwartz from Smithsonian Magazine shares. The broadcast was presented as a news report about an alien invasion, and the realistic portrayal led many listeners to believe that Earth was actually under attack. Despite multiple disclaimers throughout the broadcast, some people who tuned in late didn’t hear the clarifications and thought the world was truly ending. In several areas, there were reports of people fleeing their homes in fear, and some even packed up their cars to escape the supposed alien invaders.

The panic spread across the country because of how convincing the broadcast sounded, and it served as an early example of how media can shape perceptions of reality. The incident led to discussions about the power of radio and the responsibility of broadcasters to clarify their intentions. In the end, Welles’ fictional drama caused more harm than good, but it remains one of the most iconic moments of American mass panic over something that wasn’t real. This event also sparked a broader conversation about the potential influence of media on public behavior and fear.

5. The Satanic Panic of the 1980s and 90s

In the 1980s and 90s, America experienced a strange moral panic over supposed Satanic ritual abuse. News reports, books, and rumors spread tales of secret Satanic cults abducting children and performing horrific rituals. This panic led to dozens of criminal trials, the most famous being the McMartin preschool case, where teachers were accused of ritual abuse without solid evidence. Despite the lack of credible proof, the fear of Satanic conspiracies spread throughout society, leading to widespread public concern.

The panic was fueled by sensationalized media reports, which often exaggerated or fabricated claims. Over time, experts in psychology and law revealed that many of the accusations were based on false memories, suggestive questioning, and mass hysteria. The Satanic Panic serves as a sobering example of how fear, combined with media sensationalism, can cause entire communities to believe in something dangerous and completely unfounded. It also serves as a reminder of the importance of critical thinking when facing highly charged social issues.

6. The “Killer Bees” Panic of the 1970s

In the 1970s, a wave of fear spread across the United States regarding the invasion of Africanized “killer bees,” which were slowly migrating north from South America. News outlets sensationalized the bees as dangerous creatures capable of attacking humans in swarms, causing numerous fatalities. People started worrying about their safety, particularly in the southern and southwestern U.S., where the bees were expected to be most prevalent. Some even went so far as to install “bee-proof” protective measures around their homes and businesses in preparation for the impending invasion.

The panic reached such a point that it was commonly assumed these bees were just waiting to attack, even though Africanized bees weren’t nearly as deadly as people imagined. In reality, the bees’ behavior is not dramatically different from that of regular honeybees, and fatalities are rare. Over time, it became clear that while Africanized bees were spreading, they didn’t pose the existential threat that the media had led people to believe. This episode serves as a prime example of how exaggerated media coverage can create widespread panic over a threat that, while real, was far less dangerous than it seemed.

7. The “Cloverfield” Panic

In 2008, the release of the movie Cloverfield sparked a brief moment of panic among some viewers who mistook the promotional material for a real event. The film, which depicted a giant monster attacking New York City, used viral marketing tactics that included fake news footage, making some people believe that the events in the film might have been real. In particular, an online marketing campaign featuring faux news clips had people asking whether a mysterious creature had actually attacked the city. As a result, some individuals reacted with genuine concern, believing the footage was a live broadcast of an actual disaster.

This panic was fueled by the seamless integration of fictional footage into reality, which blurred the lines between entertainment and real life for some people. Despite the fact that Cloverfield was clearly a work of fiction, the innovative marketing caused some viewers to temporarily lose their sense of what was real. It’s a fascinating example of how immersive media and the blending of fiction with reality can manipulate people’s emotions and trigger panic. In this case, it was all a marketing strategy designed to excite, not to create actual fear.

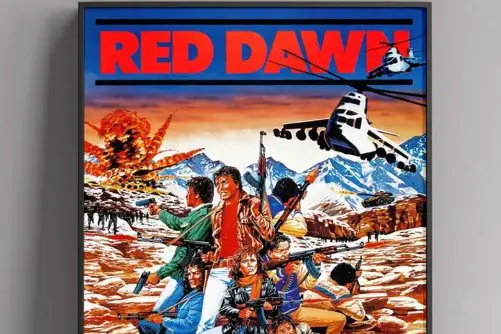

8. The “Red Dawn” Invasion Fear of the 1980s

In the early 1980s, there was widespread fear in the United States that the Soviet Union was on the brink of invading the country. This fear was fueled by Cold War tensions, geopolitical instability, and movies like Red Dawn, which depicted a Soviet and Cuban invasion of the U.S. Schools conducted drills, and some families even made preparations for an invasion that was never close to happening. People genuinely believed that war with the Soviet Union was imminent, which led to intense levels of anxiety.

This panic was largely based on the political climate of the time, but it ignored the actual military and diplomatic realities between the U.S. and the Soviet Union. The Soviet Union was not planning an invasion of the U.S., and the Cold War eventually ended with peaceful negotiations, not an all-out war. Still, the fear persisted for many years, largely stoked by media and popular culture. It’s a perfect example of how a geopolitical situation can get distorted and turn into mass fear when it’s continually exaggerated in the media.

9. The “Bermuda Triangle” Mystery

For decades, the Bermuda Triangle has been a source of mystery and panic, with theories suggesting that ships and planes vanishing in the area were the result of paranormal or extraterrestrial activity. In the 1950s and 60s, these unexplained disappearances gained so much traction that people began to fear traveling through the region at all. The media sensationalized these events, feeding the public’s fascination with the unknown and leading to widespread panic about the area. However, investigations later revealed that the majority of incidents were caused by human error, weather conditions, and mechanical failures, not supernatural forces.

Despite the debunking of many myths, the Bermuda Triangle remains a part of American lore, perpetuating a fear of something that most likely isn’t as mysterious as it seems. The Bermuda Triangle is a classic example of how a little mystery combined with overactive imaginations can lead to mass panic. While there are still occasional stories that feed the narrative, there’s no real reason to be afraid of the region. The actual reasons for the disappearances have been explained many times, but the myth continues to thrive.

10. The 1970s “Sewer Gators” Panic

In the 1970s, there was a strange, though brief, wave of panic in the U.S. about alligators living in the sewers of major cities. It was largely fueled by rumors and a few news reports claiming that alligators were being flushed down toilets and thriving in underground sewer systems. People were terrified of encountering a giant alligator in their local sewers, which led to hoaxes and widespread fear. However, there is no evidence that alligators ever made it past sewer systems’ traps and barriers to create underground populations.

The myth persisted in part because of media reports, which, despite being mostly unfounded, captured the public’s imagination. In reality, alligators are not found in urban sewers, and any sightings were most likely individual alligators that had been abandoned by pet owners. This strange moment of mass panic highlights how urban legends and exaggerations can take hold, especially when fear and curiosity combine. Even decades later, “sewer gators” remain a weird and amusing part of American folklore.

11. The “Swine Flu” Hysteria of 1976

In 1976, there was a public health scare in the U.S. over a supposed outbreak of swine flu. After a few isolated cases were reported, the government launched a massive vaccination campaign, fearing the outbreak could become a deadly pandemic similar to the 1918 Spanish flu. However, the virus didn’t spread as expected, and the vaccination program led to more reports of serious side effects than actual flu cases. Many people had been injected with a vaccine that was not necessary, and the panic turned out to be much worse than the actual threat.

This event highlights how the fear of an illness can sometimes be more dangerous than the illness itself, especially when it leads to hasty decisions and unnecessary actions. The 1976 swine flu panic also served as a cautionary tale about rushing to judgment in response to emerging health threats. While the virus turned out to be relatively mild, the vaccination campaign left many people wary of government-run public health initiatives for years to come. It’s a lesson in the importance of proportional responses to health crises.

12. The 1990s “Doomsday” Prediction

In the 1990s, there was a sudden wave of doomsday predictions, ranging from alien invasions to asteroid impacts, that set off periods of mass panic across the U.S. While none of these events came close to happening, certain predictions, like those surrounding the Hale-Bopp comet in 1997, led to widespread speculation about the world ending. People speculated that the comet’s proximity to Earth could trigger catastrophic events, and some even believed that it was a signal for the apocalypse. This panic was fueled by a combination of media sensationalism and fringe groups claiming to have special knowledge of the end of the world.

Despite the fact that Hale-Bopp posed no threat to Earth, the fear surrounding it mirrored other doomsday predictions throughout history. People sought shelter, bought survival kits, and made last-minute attempts to prepare for an event that was never coming. This episode reminds us how collective fear can be easily stoked when people are uncertain and searching for answers to things they don’t fully understand. Like other mass panics, the fear of the unknown often leads to irrational behavior and decisions.

13. The “Japanese Monster” Panic of the 1950s

In the 1950s, there were widespread rumors across the U.S. that giant, dangerous sea creatures from Japan were invading American shores. This was, of course, based on nothing but a mixture of Cold War paranoia, sensational media coverage, and old stories about sea monsters. The so-called “Japanese monster” panic reached a fever pitch in the wake of the 1954 Godzilla film’s release, which also sparked public fears of radioactive creatures. Newspapers and tabloids kept the story alive, creating a sense of impending doom that never materialized.

As is often the case with mass panics, the public’s imagination, fueled by media and cultural context, turned an innocent movie release into a nationwide scare. Despite no real evidence of such creatures, this panic underscores how fear can sometimes have a life of its own, independent of any real threats. It’s also an example of how cultural events, like films, can tap into societal fears and, in turn, create hysteria.