1. The U.S. Constitution and the Iroquois Confederacy

When the Founding Fathers were brainstorming how to build a functioning democracy, they weren’t just pulling ideas out of thin air. The Iroquois Confederacy, also known as the Haudenosaunee, had been practicing a form of representative government for centuries, according to Terri Hansen from PBS. Their Great Law of Peace emphasized checks and balances, unity among different nations, and even term limits for leaders. Benjamin Franklin and others had contact with the Iroquois and openly admired their system.

But when it came time to draft the U.S. Constitution, no one wanted to openly admit borrowing ideas from Native American governance. Instead, they leaned heavily on classical European sources like Rome and Greece, even though those systems were much less directly applicable. The Iroquois influence kind of got swept under the rug, even though it arguably had a more modern and practical approach. It’s a classic case of borrowing brilliance without giving proper credit.

2. Public Parks and the British

America loves to tout its national parks as a uniquely American innovation, but public green spaces weren’t invented here. London’s Hyde Park had been open to the public since the 1600s, offering recreation and relaxation for the masses long before Central Park was a twinkle in Frederick Law Olmsted’s eye. Even the idea of designing landscapes for public enjoyment had roots in British and French traditions, according to Tricia Kang from the Central Park Conservancy. The U.S. was late to the game, but sure made a big deal about it once it joined.

Once Central Park opened in 1858, it became a model for parks across the country. Americans praised it as a symbol of democracy and forward-thinking urban design, often ignoring that Europe had been doing it for centuries. The rhetoric made it sound like the U.S. invented parks out of sheer patriotic ingenuity. It was more of a remix than an original hit.

3. American Football and Rugby

Football is often painted as the most American of sports—gritty, strategic, and hard-hitting. But its DNA is undeniably British, tracing back to rugby and soccer (what the rest of the world calls football), according to Ben Halls from VICE. The rules of early American football were basically tweaked versions of rugby’s, and it wasn’t until the early 1900s that it really started evolving into its own game. Even then, changes like the forward pass were slow to catch on.

Despite the clear rugby origins, American culture wrapped football in red, white, and blue, treating it like a homegrown phenomenon. You’ll rarely hear fans or commentators acknowledge how much the sport owes to England. It’s been fully rebranded as an American pastime, complete with tailgates and Super Bowl commercials. But let’s be honest—it started out wearing a British jersey.

4. The Space Program and Nazi Germany

The U.S. likes to frame its space race victories as pure triumphs of American ingenuity, but the truth is way more complicated. After World War II, the U.S. brought over German scientists—including Wernher von Braun, the man behind the Nazi V-2 rocket—to jumpstart its rocket program. Operation Paperclip gave these engineers safe haven in exchange for their expertise, according to Alejandro de la Garza from TIME Magazine. Without them, NASA might have looked very different—or taken a lot longer to get off the ground.

Still, this part of the space story is often glossed over or softened in American history books. Von Braun eventually became a celebrity scientist in the U.S., hosting educational TV programs and advising Disney on space exploration. The uncomfortable origin story got buried under moon landing pride. It’s a case of rebranding borrowed brilliance without dwelling on where it came from.

5. The Metric System (Almost)

The U.S. has a weird relationship with the metric system—mostly because it almost adopted it and then just… didn’t. In the 1970s, the U.S. government made a real push to go metric, following the lead of just about every other developed nation. The metric system is easier, more logical, and used by scientists and military officials even in the U.S. But Americans didn’t want to give up their feet, gallons, and Fahrenheit.

Here’s the kicker: the metric system was originally inspired by the French Revolution, which makes the U.S. rejection a bit ironic. American culture has long prided itself on rational, Enlightenment thinking, yet it stubbornly clung to the imperial system. To this day, road signs and kitchen measurements still stand as monuments to that quiet refusal to join the rest of the world. It’s like pretending we invented a better system when we really just didn’t want to do the homework.

6. Suburbs and the Garden City Movement

Suburbs are considered a hallmark of the American Dream—white picket fences, green lawns, and all that. But the core concept was borrowed from England’s Garden City movement in the late 1800s, which aimed to create self-contained communities with green space between urban centers. These ideas crossed the Atlantic and inspired the design of places like Levittown, one of America’s first major planned suburbs. The American version just added two-car garages and strip malls.

As suburbs spread post-WWII, the U.S. treated them like a brilliant solution to urban problems—completely missing the fact that Britain had already tested and refined the idea. Planners rarely credited Ebenezer Howard, the guy behind the Garden City idea. Instead, the narrative focused on post-war prosperity and innovation. Another borrowed concept, rebranded with a stars-and-stripes spin.

7. Public Education and Prussia

The American public school system owes a huge debt to 19th-century Prussia, which developed a state-sponsored, compulsory education model designed to create disciplined, literate citizens. Horace Mann, known as the father of American public education, visited Prussia in the 1840s and came back raving about their system. He then pushed hard to implement a similar structure in the U.S., especially the standardized curriculum and age-based grade levels. Sound familiar?

Despite the Prussian blueprint, American education reformers framed it as a purely domestic innovation. Over time, the Prussian influence got filtered out of the story, and the narrative became one of American progress and democratic ideals. The irony? The system was originally designed to support a monarchy, not a democracy. But that part never made it into the school textbooks.

8. Democracy and Ancient Greece

Sure, the Founding Fathers were inspired by Ancient Greece—but the way the U.S. touts democracy as an American invention sometimes forgets that the Greeks got there a couple thousand years earlier. Athenian democracy had public assemblies, voting by citizens, and even citizen juries. The U.S. took a lot of these ideas, added a constitution, and adjusted for a much larger, more diverse population. It was a remix, not a totally new track.

Yet American civic culture often presents democracy as a homegrown virtue, born out of the Revolution and perfected over time. The references to Greece are usually surface-level—marble columns and toga imagery—without real acknowledgment of how much structural borrowing happened. And unlike the Athenians, early American democracy didn’t even let the majority of people vote. So it’s a case of copying a model and then marketing it as an upgrade.

9. The Senate and the Roman Republic

The structure of the U.S. Senate wasn’t just plucked from the minds of the Founding Fathers—it was directly inspired by the Roman Senate. The idea of a deliberative body with long terms, a sense of prestige, and a check on popular rule came straight from ancient Rome. Even the name “Senate” is a holdover from Roman times. The goal was to create a body of wise, elite leaders who could provide stability.

Of course, the U.S. adapted the concept to fit a new democratic republic, but the similarities are hard to miss. Still, American civics education tends to skip over the influence of Roman aristocracy and plays up the originality of the system. The Senate is presented as an American cornerstone, not an echo of an ancient empire. It’s another example of using the blueprint and pretending it was built from scratch.

10. Hamburger and Germany

Few foods are more iconically American than the hamburger, yet its roots are undeniably German. The dish traces back to Hamburg steak, a minced beef dish popular in northern Germany, brought over by immigrants in the 19th century. It evolved in the U.S. into a sandwich format, and from there exploded in popularity. Fast-food chains like McDonald’s helped solidify the burger as an all-American meal.

Despite the clear connection, American culture quickly adopted the burger as a national symbol, especially during the 20th century. During World War I, the name “hamburger” even got temporarily replaced with “liberty sandwich” to avoid sounding too German. The irony of celebrating a “patriotic” food with foreign roots never quite lands. It’s the culinary equivalent of copying your classmate’s homework and claiming you invented the subject.

11. Political Parties and Britain

The whole idea of formal political parties was imported from the British system of government, which had long operated with Whigs and Tories before the U.S. ever held an election. Early American leaders like George Washington even warned against political parties, but the structure took hold fast. By the time of the second U.S. presidential election, factions had already formed, echoing British party politics. It didn’t take long before the U.S. had its own version of loyal opposition and party platforms.

Despite this clear inheritance, American political culture likes to frame its party system as a unique innovation. The narrative often emphasizes fierce independence and revolutionary origins, conveniently leaving out the fact that the format was borrowed. Even the idea of an organized opposition party within a democratic government came straight from Parliament. The U.S. just rebranded it with donkeys and elephants.

12. Reality TV and the Netherlands

The U.S. may have perfected the genre, but reality TV didn’t start in Hollywood—it started in Europe, particularly the Netherlands. Shows like Big Brother and The Voice were Dutch creations before they were snapped up and remade for American audiences. These formats became cultural juggernauts in the U.S., often eclipsing their European origins. It’s easy to forget that some of America’s most-watched shows were actually imports.

Once these programs took off stateside, they were quickly rebranded with American themes, celebrities, and branding. Few people realized—or cared—that they were watching a European concept in a new outfit. It’s like buying a house someone else built, repainting it, and calling yourself the architect. Classic move.

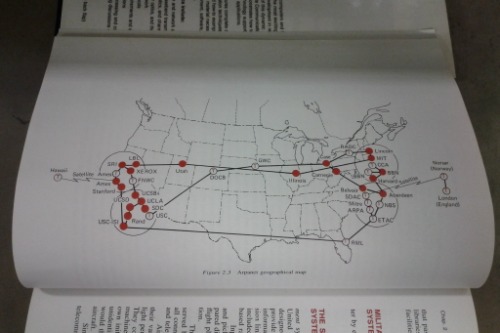

13. The Internet (Yes, Kind Of)

We love to think of the internet as an American-born marvel, and to be fair, the U.S. did play a massive role in its development through projects like ARPANET. But early ideas about interconnected computer networks were being explored in France (with Minitel), the UK, and even the Soviet Union at the same time. France’s Minitel, launched in the 1980s, was a government-sponsored precursor to the web that offered banking, messaging, and information services years before the U.S. had anything comparable. Other nations had similar experiments in digital networking that don’t get much credit.

Still, once the World Wide Web took off, the U.S. quickly claimed the internet as its own creation. Silicon Valley became the face of online innovation, and American companies dominated the digital space. The contributions of other countries faded into the background. So while the U.S. certainly helped bring the internet into full bloom, it definitely didn’t plant the first seeds—just acted like it did.