1. The War of the Worlds Radio Broadcast

On Halloween eve in 1938, Orson Welles aired a radio drama of H.G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds, presenting it as a series of live news bulletins. Listeners who tuned in late missed the intro and thought Martians were actually invading New Jersey, A. Brad Schwartz of Smithsonian Magazine explains. Panic ensued, with people fleeing their homes, jamming phone lines, and even arming themselves. Though the extent of the panic has since been debated, there’s no doubt the broadcast caused widespread confusion.

The hoax exposed how new media like radio could completely upend public perception. It also marked Orson Welles as a master of dramatic storytelling, and helped launch his legendary film career. In the fallout, networks adopted clearer disclaimers for fictional content. The incident remains a case study in media responsibility and mass hysteria.

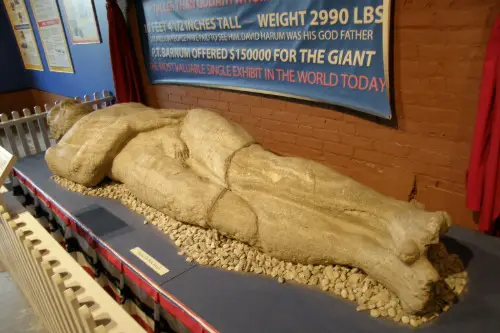

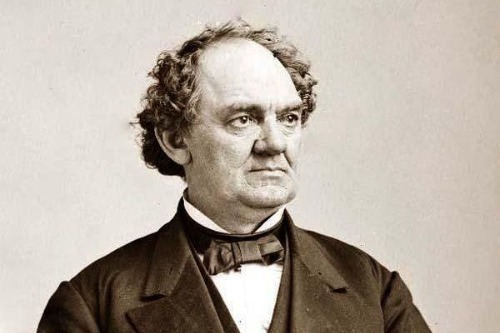

2. The Cardiff Giant

In 1869, workers digging a well in Cardiff, New York, stumbled upon what looked like a 10-foot-tall petrified man. It was actually a sculpture buried as a prank by a man named George Hull to expose the gullibility of religious believers. Still, people flocked from all over to see the “giant,” with some insisting it was solid proof of biblical giants, according to Kate Eschner of Smithsonian Magazine. Even respected scientists debated its authenticity before it was revealed as a hoax.

The giant was such a hit that P.T. Barnum even tried to buy it—and when he couldn’t, he made a copy and claimed his was the real one. Hull had carved it from gypsum and stained it with acid to give it an ancient look. The prank ended up being a national sensation and highlighted how easy it was to manipulate both faith and science. Today, the Cardiff Giant is still on display at a museum in Cooperstown, New York.

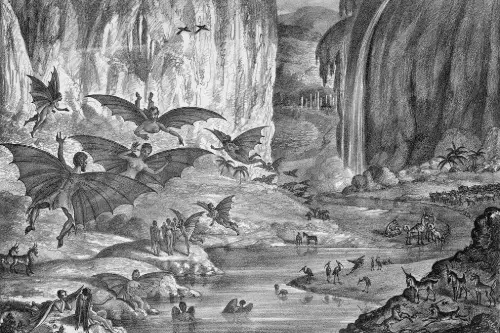

3. The Great Moon Hoax of 1835

Back in the 1830s, readers of The Sun, a New York newspaper, were captivated by reports that life had been discovered on the moon, Kevin Young of The New Yorker shares. The articles described bat-like humanoids, unicorns, and lush lunar landscapes—completely fabricated, of course. The hoax was presented as a legitimate scientific report, allegedly from a famous astronomer, Sir John Herschel. People believed it for weeks before the paper casually admitted it was all made up.

The reason it worked? Newspapers were a primary source of information, and science was something the average reader couldn’t easily fact-check. Plus, the idea of extraterrestrial life was both thrilling and plausible at the time. The hoax made The Sun wildly popular, increasing circulation dramatically.

4. The Balloon Boy Incident

In 2009, America was glued to the sky as a silver balloon floated across Colorado, allegedly carrying six-year-old Falcon Heene. After hours of rescue efforts and live coverage, Falcon was found hiding safely in his family’s attic. Turns out, the whole thing had been orchestrated by his parents in a bid for reality TV fame. The story unraveled quickly after Falcon accidentally admitted during an interview, “You guys said that, um, we did this for the show.”

The public was outraged, and authorities were too—both parents faced criminal charges and were ordered to pay restitution. It was a modern hoax that showed how the desire for attention can override ethics. The incident also raised serious questions about media sensationalism. In 2020, the Heenes were officially pardoned by the Colorado governor, according to Wilson Wong from NBC News.

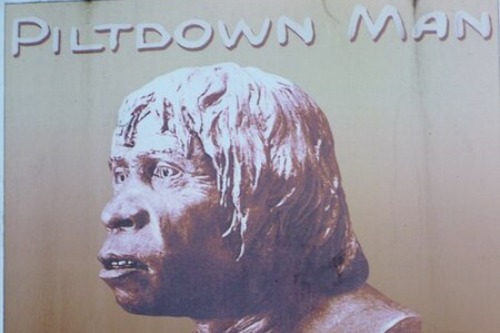

5. The Piltdown Man

Though not strictly American, the Piltdown Man hoax deeply influenced American science and anthropology. Discovered in England in 1912 but studied and embraced globally, this supposed “missing link” between ape and human misled scientists for over 40 years. It was later revealed to be a human skull fused with an orangutan jaw, stained to look ancient. Many American researchers based evolutionary theories on it, making the fallout massive when the truth came out in 1953.

The hoax succeeded partly because it confirmed preconceived ideas about human evolution at the time. American textbooks and universities taught about Piltdown as fact, showcasing how even academia can be deceived. Its exposure forced scientists to adopt stricter standards of evidence. It’s a cautionary tale about bias and scientific rigor that still resonates today.

6. The Howard Hughes Autobiography Scam

In 1971, author Clifford Irving convinced Life magazine and publisher McGraw-Hill that reclusive billionaire Howard Hughes had chosen him to write his autobiography. He faked letters, held forged interviews, and even got paid a massive advance. The hoax unraveled when the real Hughes, who hadn’t been seen publicly in years, held a rare phone interview to deny the whole thing. It was one of the boldest literary scams in American history.

Irving went to prison, but the spectacle captivated the country. The story revealed how secrecy around public figures creates room for manipulation. It also showed the publishing industry’s vulnerability to charismatic storytellers. Irving’s hoax was later dramatized in a 2006 film starring Richard Gere.

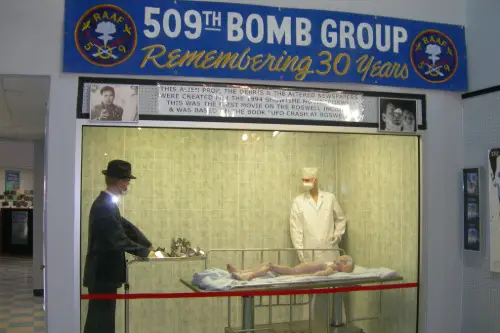

7. The Roswell UFO Incident

In 1947, something crashed near Roswell, New Mexico, and the military initially claimed it was a “flying disc.” They quickly retracted that, saying it was just a weather balloon—but the damage was done. Conspiracy theories took off, fueled by secrecy and later declassified projects like Operation Mogul. For decades, Roswell was seen as the smoking gun for UFO believers.

It fooled the public because the government’s shifting story bred mistrust. The incident launched America’s modern obsession with aliens and government cover-ups. It inspired movies, books, and even a museum. Whether you believe in UFOs or not, Roswell became a defining part of American pop culture.

8. The PT Barnum “Fiji Mermaid”

In the 1840s, showman P.T. Barnum debuted what he claimed was a real mermaid—half fish, half woman. It turned out to be the mummified remains of a monkey stitched to a fish, but people bought into it. Barnum marketed it as a marvel of natural science and used it to boost ticket sales. The public flocked to see the bizarre creature, many believing it was genuine.

The hoax worked because Barnum was a master of blending science, myth, and showmanship. It also tapped into people’s fascination with the exotic and unexplained. Barnum later admitted to the ruse, saying he wanted to “show how easily people could be deceived.” It’s one of the earliest examples of viral marketing in American history.

9. The Sokal Affair

In 1996, physicist Alan Sokal submitted a nonsensical academic paper to the cultural studies journal Social Text to see if they’d publish it. Titled “Transgressing the Boundaries: Toward a Transformative Hermeneutics of Quantum Gravity,” it was intentionally loaded with jargon and meaningless ideas. The journal published it, and Sokal later revealed the hoax in a separate article. It sparked a firestorm in academia and the media alike.

Sokal’s goal was to critique postmodernism and the lack of rigor in some parts of academic publishing. It worked because it exposed how style could trump substance when ideology was involved. The affair triggered debates about peer review, truth, and the politicization of scholarship. It’s still referenced in discussions about academic integrity today.

10. The Hitler Diaries

In 1983, a German magazine claimed to have obtained Hitler’s personal diaries and shared them with the world. Several American outlets ran with the story, believing it was a monumental historical discovery. But the diaries were quickly proven fake—they were modern forgeries made with postwar ink and materials. The scandal embarrassed historians and newsrooms alike.

American audiences were captivated because the idea of peering into Hitler’s mind was irresistible. The hoax exposed how even major institutions could fail at due diligence under the pressure of breaking a big story. It reminded journalists and historians of the importance of verification. The fallout was severe enough to end careers and reputations.

11. The Paul Is Dead Rumor

In the late 1960s, a bizarre rumor spread across the U.S. that Paul McCartney of The Beatles had died and been replaced by a look-alike. Clues were allegedly hidden in album covers, lyrics, and even reversed audio messages. American college students dissected records, held forums, and called into radio shows to discuss it seriously. The Beatles even had to publicly deny it.

What made the hoax so powerful was how fans turned into amateur detectives. The media frenzy showed how suggestible people could be when piecing together unrelated facts. It also reflected the growing power of pop culture to shape national narratives. Despite being completely false, the rumor helped sell millions of records.

12. The Lying Memoir of James Frey

James Frey’s 2003 memoir A Million Little Pieces was hailed as a raw, brutal tale of addiction and recovery. It was even selected for Oprah’s Book Club, catapulting it to best-seller status. But in 2006, The Smoking Gun revealed that large parts of the story were exaggerated or fabricated. Frey had invented arrests, jail time, and other key details.

The public backlash was intense, especially after Oprah confronted him on her show. The scandal raised questions about truth in memoirs and the responsibilities of publishers and authors. It also sparked a wave of more careful fact-checking in nonfiction publishing. Frey eventually apologized, but the damage was done.

13. The Manti Te’o Girlfriend Hoax

In 2013, America was stunned to learn that Notre Dame football star Manti Te’o’s inspirational story about losing his girlfriend to cancer was false. The girlfriend, Lennay Kekua, didn’t exist—it was all an elaborate catfishing scheme. Te’o said he had been duped, and after some confusion, it became clear he was a victim, not a co-conspirator. Still, it left the country baffled about how something like that could happen.

The story had captured hearts nationwide and was even used to bolster his Heisman campaign. It worked because it played into a classic emotional arc of love, loss, and perseverance. The internet and social media made the deception easier and more believable. Netflix later turned the saga into a documentary, further cementing its place in pop culture.