1. Pet Rock (1975)

In the mid-1970s, Gary Dahl turned a literal rock into a multimillion-dollar novelty. Packaged in a cardboard box with breathing holes and straw, the Pet Rock came with a 32-page training manual. It was entirely tongue-in-cheek—after all, rocks don’t need feeding, walking, or grooming. Americans loved the absurdity, buying over a million of them in just a few months.

What made it work was the perfect storm of kitschy humor and low price point—only $3.95. It became a cult sensation, showing the power of marketing over utility. In a way, the Pet Rock was a parody of consumerism that people embraced with full sincerity. Its brief but bright success made it a classic example of American novelty culture.

2. Clackers (late 1960s–early 1970s)

Clackers were two acrylic balls on a string that kids would swing up and down until they smacked together, making a satisfying “clack” sound. They were mesmerizing to play with and surprisingly tricky to master. The toy gained massive popularity through word of mouth and simple playground appeal. But they were also pretty dangerous—shards from broken Clackers reportedly flew like glass shrapnel.

The toy was eventually banned by the Consumer Product Safety Commission in the 1970s. Still, its wild popularity before the crackdown shows just how much kids loved chaos in plastic form. It worked because it was hypnotic, kinetic, and competitive—perfect for the analog era of childhood. Even today, people remember Clackers with a weird mix of nostalgia and fear.

3. The Flowbee (1988)

When it hit the market, the Flowbee seemed like a joke: a haircutting vacuum that attached to your home vacuum cleaner. But it actually worked—and more than two million were sold. The gadget let users cut their own hair evenly and quickly without making a mess. It promised a clean cut every time, even if it made you look like an astronaut grooming in zero gravity.

Its biggest boom came during the DIY-obsessed late ’80s and early ’90s. And it saw a surprising resurgence during the COVID-19 pandemic when people couldn’t get to salons. The Flowbee succeeded because it was genuinely practical for the right kind of user. Plus, it had just the right amount of weird to become a cultural touchstone.

4. Tupperware Parties (1950s onward)

Tupperware itself wasn’t weird—durable plastic containers were and still are extremely useful. What made it strange was the direct sales model: women hosting “Tupperware Parties” in their homes. These gatherings blurred the line between social events and sales pitches. Yet they empowered housewives to earn money in an era when career paths for women were limited.

The method worked because it tapped into social networks in an analog world. Tupperware became a status symbol of domestic efficiency and female entrepreneurship. The whole setup was quirky—plastic bowls as the centerpiece of a suburban soirée—but it clicked with mid-century sensibilities. It sold millions and changed the way America bought products.

5. The Chia Pet (1982)

“Ch-ch-ch-Chia!” The jingle was half the charm of the Chia Pet, a terra-cotta figurine that sprouted chia seeds into “fur” or “hair.” Whether shaped like a ram, a hippo, or eventually even human heads like Bob Ross, the concept was silly on its face. But it sold like crazy, especially around the holidays.

The appeal was part gardening project, part gag gift. People liked watching their plant “grow,” even if it only lasted a couple of weeks. It didn’t do much, but it made people smile—and that was enough. The Chia Pet stuck around because it found the sweet spot between novelty and nostalgia.

6. Sea-Monkeys (1960s)

Sea-Monkeys were really just brine shrimp, but their ads promised a fantasy—tiny aquatic people living in your tank. Marketed with elaborate comic-book illustrations, kids were lured in by images of crown-wearing creatures playing games underwater. In reality, you got a bunch of barely visible squiggles. But somehow, that didn’t kill the dream.

The reason it worked was that it gave kids a sense of ownership over something “alive.” The kits felt like a science experiment and a pet all rolled into one. The bait-and-switch visuals might be infamous, but they also made Sea-Monkeys unforgettable. They thrived on imagination, and for a while, that was more than enough.

7. The Rejuvenique Face Mask (1999)

At first glance, the Rejuvenique Face Mask looked like something out of a horror movie. It was a rigid, expressionless plastic mask that strapped onto your face and delivered tiny electrical shocks to “tone” your facial muscles. Marketed with the promise of a non-invasive facelift, it claimed to reduce wrinkles through “facial exercise.” The effect was more terrifying than rejuvenating, but it definitely got people’s attention.

It sold for around $200 and had its moment on late-night infomercials, especially because it came with a celebrity endorsement from Linda Evans of Dynasty fame. People were intrigued by the high-tech promise of beauty without surgery—even if it meant looking like a cyborg for 15 minutes a day. It worked not because of hard science, but because it fed into 1990s anti-aging obsession. The Rejuvenique mask was bizarre, slightly creepy, and oddly unforgettable—making it a perfect fit for this list.

8. The Ginsu Knife (1978)

The Ginsu Knife infomercial was a masterclass in over-the-top salesmanship. With dramatic demonstrations—slicing through cans, then tomatoes with surgical precision—it became impossible to look away. The knives weren’t revolutionary in design, but the pitch made them seem like the Excalibur of the kitchen. “But wait, there’s more!” became an enduring catchphrase thanks to Ginsu.

Americans bought millions of them, seduced by the promise of durability, value, and free bonus items. The brand name even sounded Japanese, though the product was made in Ohio. What made it work was a perfect mix of flashy presentation and perceived practicality. It wasn’t just a knife—it was an experience you couldn’t resist for $19.95.

9. Mood Rings (1975)

The mood ring claimed to reflect your emotional state through changes in color. In reality, it was just a thermochromic liquid crystal responding to body temperature. But the illusion of emotional insight gave it an almost mystical appeal. It debuted during a time when self-expression and pseudo-science were both booming.

Mood rings became a full-blown fad within weeks. Teenagers especially loved the idea that their jewelry could “read” them. Even though the science was bogus, the magic felt real enough. Its weirdness was its charm, and that’s what kept them flying off shelves.

10. Easy-Bake Oven (1963)

The Easy-Bake Oven let kids cook mini cakes using a 100-watt light bulb. Yes, just a light bulb. It sounded completely ridiculous, but it actually worked—and it was incredibly satisfying. The kits came with mixes and tiny pans, making kids feel like real chefs.

It was a runaway hit, selling over 500,000 units in its first year. The appeal was half toy, half appliance, and totally empowering for a generation of young bakers. It hit the market at a time when domesticity was being taught early. Somehow, baking with a light bulb turned into a rite of passage.

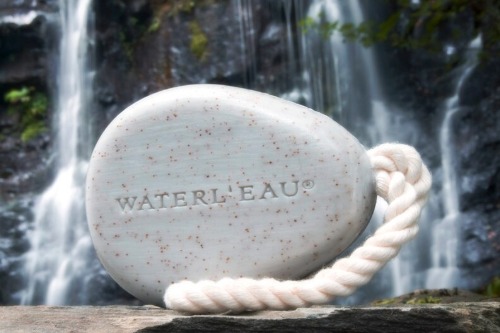

11. Soap-on-a-Rope (1950s–1970s)

At first glance, it seems absurd—why would soap need a rope? But soap-on-a-rope became a common sight in mid-century bathrooms, often given as a gift for dads or grandpas. It was supposed to prevent slippery bars from falling in the shower. And it added just enough novelty to an otherwise boring product to make it fun.

This hybrid of hygiene and convenience caught on thanks to creative marketing. Companies leaned into its kitschiness with novelty shapes and masculine scents. It worked because it solved a small problem in a delightfully quirky way. And for some, it was the perfect gag gift that actually got used.

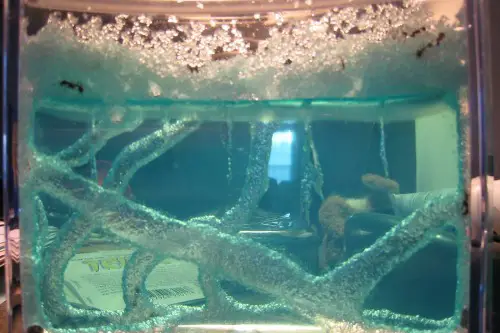

12. The Ant Farm (1956)

Created by entrepreneur Milton Levine, the Ant Farm was exactly what it sounds like—a thin, plastic enclosure where kids could watch ants dig tunnels. It turned live insects into entertainment and education, all in one strange little package. The original versions came with sand and a coupon to mail away for real, live ants. It was part toy, part science kit, and completely bizarre when you really think about it.

But it worked because it tapped into natural childhood curiosity. Watching ants work their tiny architectural magic was oddly mesmerizing. It was a hands-off pet, a living display, and a conversation starter all at once. The Ant Farm sold millions and became a staple of American playrooms, proving that even bugs could be a hit with the right plastic case.

This post 12 Vintage American Products That Were Just Weird Enough to Work was first published on American Charm.