1. The Statue of Liberty

Most people see the Statue of Liberty as a bold symbol of freedom and democracy—Lady Liberty holding her torch high for all who come to America. But it was originally conceived more as a celebration of the end of slavery than as a welcome mat for immigrants, according to Gillian Brockell from The Washington Post. If you look closely, you’ll see broken chains and shackles at her feet, symbolizing liberation. The torch was meant to light the way to liberty, especially for those who had been oppressed.

Over time, though, the narrative shifted, especially with the influx of immigrants through Ellis Island. The poem by Emma Lazarus—“Give me your tired, your poor…”—reframed her image into one of immigration and hope. That message stuck, and now most people forget her abolitionist roots. She’s still a beacon, but her original meaning was tied more directly to freedom from slavery.

2. Mount Rushmore

To many, Mount Rushmore is a patriotic shrine to four great presidents, carved boldly into the Black Hills of South Dakota. But the monument is also deeply controversial because it was built on land sacred to the Lakota Sioux, taken from them in violation of treaties, according to PBS. Not to mention, the sculptor, Gutzon Borglum, was affiliated with the Ku Klux Klan and had some pretty questionable views. It’s not just a national monument—it’s a political and cultural flashpoint.

While the presidents were chosen to represent America’s birth, growth, development, and preservation, the monument has a darker undercurrent. For the Lakota, it’s a symbol of betrayal and stolen land, rather than national pride. That’s why it’s sometimes referred to as a monument to colonialism by Native activists. Understanding that context totally changes how you look at those stone faces.

3. The Liberty Bell

The Liberty Bell is often associated with the American Revolution and the ringing in of independence. But it actually wasn’t rung on July 4, 1776, as many people think. The bell didn’t gain its fame until nearly 70 years later, when abolitionists adopted it as a symbol of the fight to end slavery, according to Gary B. Nash from the Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia. They were the ones who first called it the “Liberty Bell.”

Originally, it was just the bell in the Pennsylvania State House, and it wasn’t treated with much reverence. But as abolitionists searched for powerful imagery, they latched onto the cracked bell and its inscription: “Proclaim Liberty Throughout All the Land…” That slogan became a rallying cry, and the bell’s fame grew. Its modern symbolism owes far more to the Civil War era than to the Revolutionary War.

4. The Alamo

The Alamo is widely remembered as a heroic last stand by Texans against Mexican forces in 1836. “Remember the Alamo” became a cry for independence and bravery, but the real story is a lot more complicated. Many of those who fought at the Alamo were defending the right to maintain slavery, which Mexico had outlawed. So while the battle was about independence, it was also tangled up with the issue of preserving slaveholding power, according to Bryan Burrough and Jason Stanford from TIME Magazine.

Today, the Alamo is seen by many as a sacred Texas monument, almost mythologized in popular culture. But for others, it represents the darker side of American expansion and the complexities of the fight for independence. Knowing that the defenders were not just freedom fighters but also fighting against anti-slavery laws puts the whole narrative into a new light. It’s a lot less black and white than the legends suggest.

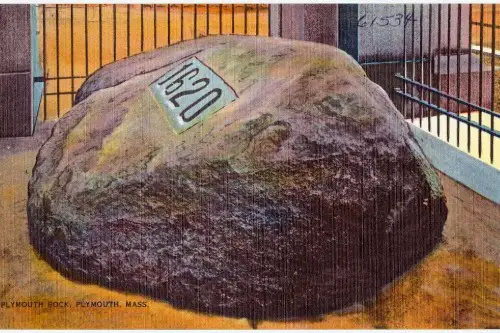

5. Plymouth Rock

Plymouth Rock is supposed to be the exact spot where the Pilgrims first stepped onto American soil in 1620. But here’s the thing—there’s no solid evidence that they ever landed on that rock at all. In fact, the story didn’t even appear in writing until more than a century later. It was essentially picked at random and turned into a symbol.

Despite the myth, Plymouth Rock has become a central icon of America’s origin story. It’s treated with reverence as if it’s a foundational piece of U.S. history. But its meaning is more symbolic than factual, and it glosses over the colonization and displacement that followed. So, it’s more of a chosen myth than a historical marker.

6. The Jefferson Memorial

The Jefferson Memorial honors Thomas Jefferson as a founding father and author of the Declaration of Independence. The dome, columns, and statue project wisdom and enlightenment, reinforcing the idea of Jefferson as a principled architect of liberty. But the monument was also a product of 1940s politics, meant to boost American ideals during WWII. It was about rallying public morale more than commemorating Jefferson himself.

And while Jefferson’s words about equality are quoted everywhere, the memorial doesn’t acknowledge his contradictions. He owned hundreds of enslaved people, and his relationship with Sally Hemings—an enslaved woman—adds a whole layer of complexity. The monument portrays a simplified version of Jefferson, carefully curated to fit a national narrative. What it leaves out speaks as loudly as what it includes.

7. The Lincoln Memorial

Most visitors see the Lincoln Memorial as a powerful tribute to the man who ended slavery and preserved the Union. But it was actually designed to be more about unity than justice. When it was dedicated in 1922, the speakers avoided direct discussion of emancipation, and it was during a time when segregation was still in full force—even the audience at the dedication was racially divided. The statue itself was meant to project calm strength, not revolution.

It wasn’t until the Civil Rights Movement that the memorial took on new significance. Martin Luther King Jr. gave his “I Have a Dream” speech on its steps, forever changing its symbolic role. Today, people see it as a monument to justice, but that meaning came from the people—not the original intent. The Lincoln Memorial’s message evolved as the country did.

8. The Washington Monument

The Washington Monument is a towering symbol of national pride, meant to honor George Washington as the first president and a unifying leader. But its construction was delayed for decades due to intense political and financial conflict—including a battle over slavery. Originally started in 1848, work halted in the 1850s, partly because anti-slavery activists objected to donors like the Pope and Southern slaveholders. It sat half-finished for years.

When construction resumed after the Civil War, a lot of compromises had to be made. That’s why you can see a clear line where the stone changes color partway up. It reflects a nation divided, even in the act of honoring its first president. The monument’s clean lines hide a pretty messy backstory.

9. The Gateway Arch

Most people think of the Gateway Arch in St. Louis as a tribute to westward expansion and frontier spirit. But what many don’t realize is that it’s also a monument to manifest destiny, a controversial ideology that justified American territorial conquest. The expansion it celebrates came at the cost of Native American displacement and violence. The arch marks the “Gateway to the West”—but for whom?

When it was completed in 1965, it was also a statement of modern design and Cold War-era optimism. It was meant to show off American ingenuity, not just history. But the sanitized story of exploration leaves out the exploitation that came with it. It’s a sleek, shining symbol with a complicated legacy.

10. The Bunker Hill Monument

The Bunker Hill Monument in Boston commemorates one of the first major battles of the American Revolution. But here’s a fun twist: the battle mostly took place on nearby Breed’s Hill. Due to a mix-up in naming, the monument actually doesn’t sit on the main site of the action. Still, the name stuck, and the monument became symbolic of American resolve.

Despite the location confusion, the monument became a rallying point for American nationalism in the 19th century. It also helped kick off a wave of patriotic monument-building. What’s funny is that the actual military result of the battle was a British victory—but the heavy losses they suffered made it a moral win for the Americans. The monument commemorates more myth than military triumph.

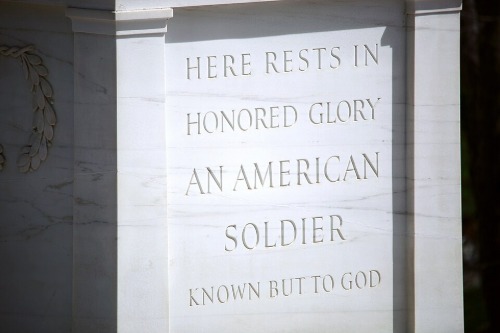

11. The Tomb of the Unknown Soldier

The Tomb of the Unknown Soldier in Arlington National Cemetery is seen as a sacred tribute to unidentified service members who died in war. It’s visited by millions and guarded 24/7, symbolizing ultimate respect and gratitude. But its origins are rooted in a very specific political effort after World War I to help unify a grieving, fractured country. It was about giving closure to families who never got a body back.

Over time, the meaning expanded to honor all unknown service members from multiple wars. But the original focus was on World War I’s mass casualties and the emotional toll of industrialized warfare. It was as much about national healing as it was about valor. The monument’s broader message grew later, shaped by the collective need for remembrance.

12. The Confederate Memorial at Arlington

This one’s especially complex. The Confederate Memorial in Arlington National Cemetery, installed in 1914, was designed to honor Confederate soldiers—but it was also very much a product of the Jim Crow era. It presents a romanticized version of the Confederacy, showing enslaved people as loyal and happy, which is obviously not historically accurate. It was intended to promote reconciliation—but only under terms that favored the Southern narrative.

For decades, the memorial stood without much controversy, as the “Lost Cause” ideology gained traction in textbooks and popular culture. But in recent years, it’s come under intense scrutiny for promoting a distorted history. Many now see it not as a symbol of unity, but of white supremacy and historical revisionism. It’s a reminder that monuments aren’t just about the past—they shape how we see it.