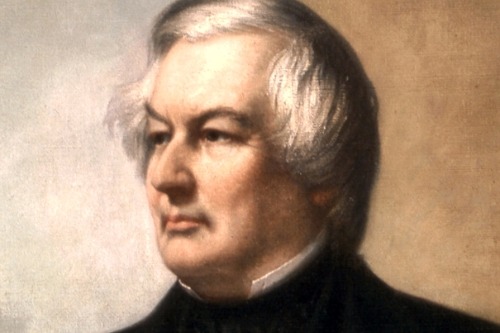

1. Millard Fillmore – The President Who Sent the Navy to Make Friends in Japan

Millard Fillmore doesn’t usually make it onto presidential trivia nights, but his decision to send Commodore Matthew Perry to Japan in 1852 opened the country to Western trade after centuries of isolation, according to Michael Holt from the Miller Center. It was a bold, almost audacious move for a man often labeled as forgettable. While Perry technically arrived under President Franklin Pierce, the entire mission was Fillmore’s brainchild. In a way, he’s the reason you can buy sushi in Iowa.

But Fillmore’s Japan gambit wasn’t his only quirky move. He also supported the deeply controversial Fugitive Slave Act, which forced officials in free states to return escaped enslaved people. That decision fractured his party and essentially ended his political career. So he opened Japan, but helped close the door on national unity.

2. John Tyler – The President Who Became a Confederate

John Tyler had one of the strangest post-presidency paths in American history. After serving from 1841 to 1845, he later sided with the Confederacy during the Civil War and even got elected to their Congress, according to William Freehling from the Miller Center. That makes him the only U.S. president to be officially considered a traitor by the Union. He died before taking his seat, but the damage to his legacy was done.

Before all that, Tyler set a major precedent: he was the first vice president to become president due to the death of his predecessor, William Henry Harrison. People at the time called him “His Accidency” because they weren’t sure a veep could even take over. But Tyler dug in, took the oath, and reshaped how presidential succession worked forever. It was a strange twist of fate that redefined the office.

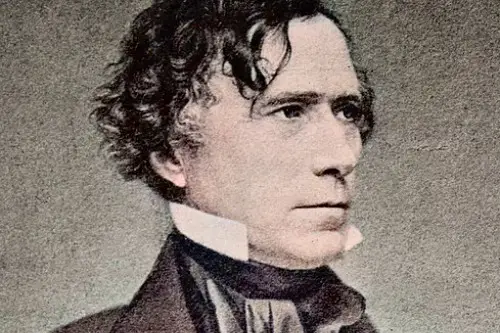

3. Franklin Pierce – The Emo President Who Drank His Way Through Disaster

Franklin Pierce had one of the most tragic presidencies, shadowed by personal grief and national disarray. He lost all three of his children, the last in a train accident just before his inauguration, and it’s widely believed he never emotionally recovered, according to Michael F. Holt from Oxford Academic. He turned increasingly to alcohol and struggled to lead a country on the brink of civil war. He signed the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which led to violent conflict over slavery and edged the nation closer to crisis.

Despite being a Northern Democrat, Pierce often sided with Southern interests, earning fierce backlash. His own party refused to re-nominate him, which was rare and humiliating. He ended his life in obscurity and alcoholism, basically abandoned by the nation he once led. If Pierce shaped anything, it was how not to steer a country through tension.

4. Chester A. Arthur – The Spoils System Guy Who Shocked Everyone

Chester A. Arthur was widely seen as a corrupt party hack before he took office, thanks to his ties to the infamous New York political machine. But after President James Garfield was assassinated, Arthur shocked everyone by embracing civil service reform. He pushed through the Pendleton Act, which began dismantling the “spoils system” of handing out government jobs as political favors. It was one of the most unexpected presidential glow-ups in history, according to Scott S. Greenberger from The Washington Post.

Arthur also had a flair for the fashionable—he redecorated the White House with Tiffany & Co. and owned over 80 pairs of pants. But despite his style and reform, he didn’t run for re-election, partly due to a secret illness he kept hidden. He had Bright’s disease, a fatal kidney condition, and quietly slipped out of politics. He went from corrupt insider to principled reformer, and then vanished.

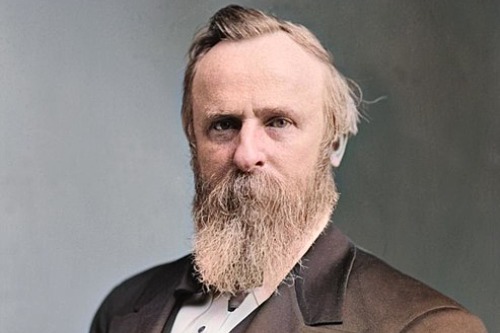

5. Rutherford B. Hayes – The President Who Ended Reconstruction with a Backroom Deal

Rutherford B. Hayes didn’t win the presidency so much as he bargained his way into it. After the disputed election of 1876, Hayes made a secret deal with Southern Democrats: in exchange for their support, he’d pull federal troops out of the South. That move officially ended Reconstruction and effectively abandoned the rights of newly freed Black Americans. It shaped the South’s future for decades—and not in a good way.

Hayes called his presidency a “quiet” one, but that’s a wild understatement given the consequences of his compromise. It led to the rise of Jim Crow laws and decades of systemic racial oppression. Strangely, he also pushed for civil service reform and better treatment of Native Americans—efforts that mostly got lost in the shadow of that infamous deal. Hayes was complex, but history remembers the trade.

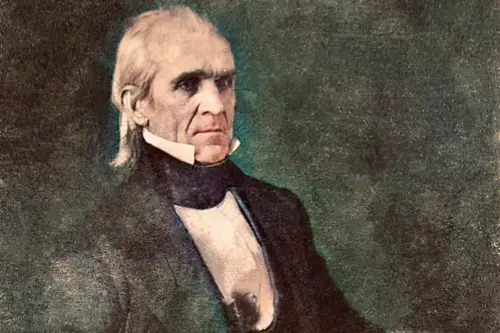

6. James K. Polk – The One-Term Wonder Who Grabbed Half of Mexico

James K. Polk promised to serve just one term—and then basically redrew the map of North America. Under his leadership, the U.S. fought the Mexican-American War, adding vast territory including California, Arizona, and New Mexico. He also finalized the Oregon Territory deal with Britain, securing the Pacific Northwest. All of this fulfilled his vision of Manifest Destiny.

Polk worked nonstop, micromanaged his cabinet, and reportedly left the office physically exhausted. He kept his one-term pledge and died just three months after leaving office. Today, few people outside history nerd circles talk about him, but he expanded the U.S. more than most presidents. His legacy is huge, even if his name isn’t.

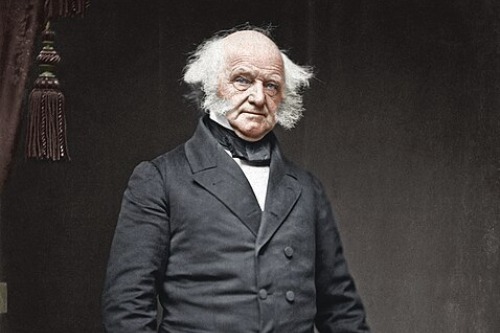

7. Martin Van Buren – The Original Politician Who Couldn’t Handle a Crisis

Martin Van Buren was a political mastermind—the architect of the Democratic Party and a slick behind-the-scenes operator. But once he actually became president, the economy imploded. The Panic of 1837 hit early in his term, and his response was to do… almost nothing. He believed the government shouldn’t intervene, which didn’t help anyone.

Despite that, Van Buren was a trendsetter in other ways—he was the first president born a U.S. citizen and the first from New York. He even ran again later under a third party, the Free Soil Party, to oppose the expansion of slavery. It didn’t go anywhere, but it was kind of gutsy. He shaped political machines and parties, but froze when it really mattered.

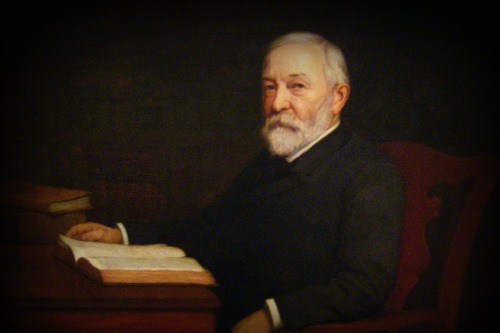

8. Benjamin Harrison – The Human Iceberg Who Wired the White House

Benjamin Harrison got stuck between two terms of Grover Cleveland, so people often forget he existed at all. But he brought electricity to the White House—even if he was too afraid to use the light switches himself. He also signed the Sherman Antitrust Act, the first major step in regulating big business monopolies. That one law would later be used against giants like Standard Oil.

Harrison wasn’t exactly charismatic—reporters called him the “Human Iceberg” because of his frosty demeanor. But he took a stand on civil rights, supporting a federal voting rights bill for Black Americans (though it failed in the Senate). He also expanded the Navy and admitted six new states to the Union. Cold in tone, but impactful in policy.

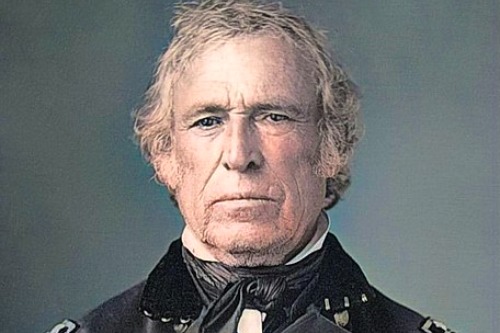

9. Zachary Taylor – The General Who Ate Himself to Death

Zachary Taylor wasn’t much of a politician—he’d never even voted before becoming president. He was a war hero from the Mexican-American War, and people loved his no-nonsense, rough-around-the-edges persona. But just 16 months into his presidency, he died suddenly after eating a bunch of cherries and iced milk on a hot day. Some conspiracy theories claim he was poisoned, but most historians think it was just a really bad case of gastroenteritis.

Before his death, Taylor had taken a surprisingly strong stand against expanding slavery into new territories. It was a bold position for a Southern slaveholder and war general. His death cleared the way for the Compromise of 1850, which tried—and failed—to hold the Union together. Taylor didn’t last long, but his short tenure left a mark.

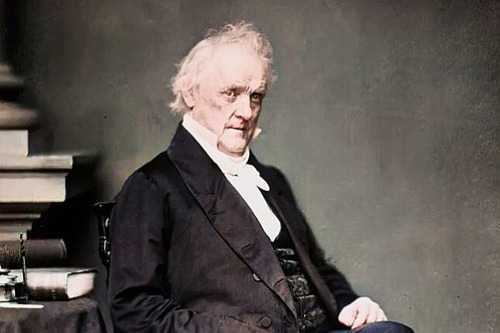

10. James Buchanan – The President Who Let the Union Burn

James Buchanan holds the unfortunate title of “Worst President Ever” in many historians’ rankings. He watched as Southern states began seceding and basically did nothing, believing it was illegal for them to leave—but also illegal for him to stop them. His inaction gave the Confederacy a head start and made Abraham Lincoln’s job infinitely harder. It was a slow-motion disaster.

Strangely, Buchanan was incredibly experienced—he’d been a senator, ambassador, and secretary of state. But when it came time to lead, he froze. He also supported the pro-slavery Dred Scott decision, which inflamed tensions further. America needed a fire extinguisher, and Buchanan brought gasoline.

11. Herbert Hoover – The Engineer Who Couldn’t Build a Way Out

Before becoming president, Herbert Hoover was a globally respected humanitarian who organized food relief for Europe during and after World War I. But when the Great Depression hit, he clung to his belief in voluntary aid and limited government. That hands-off approach proved disastrous as banks failed and unemployment soared. People blamed him personally—hence the term “Hoovervilles” for the shantytowns that popped up across the country.

Hoover did eventually approve some public works programs, but they were too little, too late. He lost in a landslide to FDR, who took a radically different approach. Hoover’s fall from global hero to national scapegoat was swift and brutal. He lived for decades after leaving office, but never shook the shadow of the Depression.

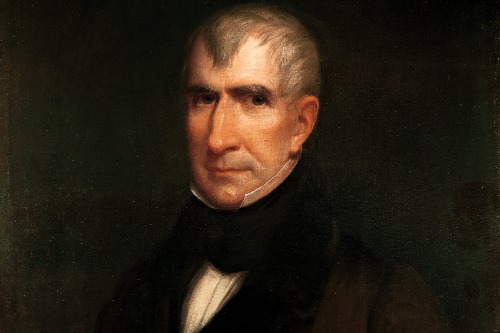

12. William Henry Harrison – The President Who Died Before Doing Anything… Except One Thing

William Henry Harrison is mostly famous for dying just 31 days after taking office—the shortest presidency ever. He caught pneumonia after giving a two-hour inaugural address in cold, wet weather without a coat. But in those four weeks, he managed to set one very important precedent: that the presidency belongs to the person elected, not to Congress or a party boss. He pushed back on attempts to control his decisions, even as he lay dying.

Harrison had been a military hero and territorial governor before becoming president, known for fighting in the Battle of Tippecanoe. His presidency was short, but his stubborn assertion of executive authority shaped how future presidents governed. In death, he did more than many do in life. That’s pretty strange—and kind of powerful.